|

Survivors of sex abuse by nuns suffer decades of delayed healing

By Dawn Araujo-Hawkins

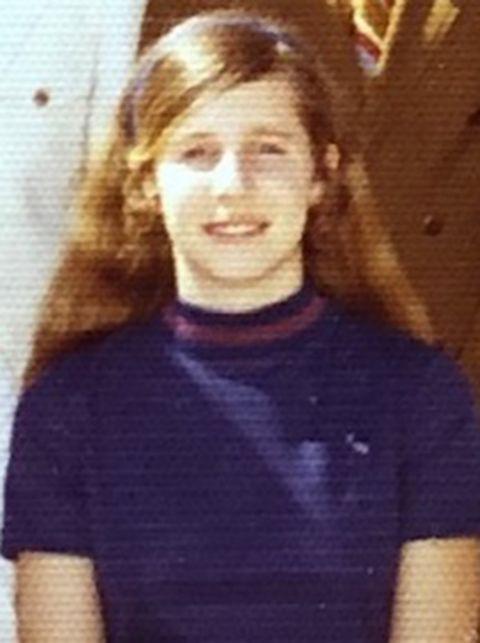

[with pdf] Anne Gleeson was 12 years old when she says Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet Judith Fisher — her charismatic, redheaded history teacher at Immacolata School in Richmond Heights, Missouri — began singling her out for special attention. "She'd wander around the classroom, and she'd lean on my chair and press her fingers into my back. Or she'd send me a little note or leave a present in my desk," Gleeson, now 63, said. The secret, forbidden touches gave Gleeson shivers. She says the rape began in 1971 when she was 13, although it would take three decades and some therapy for her to recognize it as such. In Gleeson's adolescent mind, she was simply head over heels in love with a woman 24 years her senior. The sexual contact happened anywhere and everywhere, Gleeson said: in stairwells at the school, in Fisher's bedroom at the convent, on the overnight trips Fisher arranged with Gleeson's mother and another Sister of St. Joseph. "To me, it was almost miraculous," Gleeson told Global Sisters Report. "I was even kind of jealous of the ring on her finger. She was the bride of Christ — and, yet, she told me that we would always be together forever." According to the watchdog group BishopAccountability.org, as of September 2020, 162 women religious have been publicly accused of sexual abuse in the United States. Mary Dispenza, who heads the subgroup within the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests (SNAP) for those abused by Catholic sisters, has received more than 90 phone calls and emails with stories of both physical and sexual abuse, about 60 of them just in the last two years. But Dispenza, a former Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary, suspects that the real total might be in the thousands. After all, there are more than 6,700 credible abuse accusations against priests, and women religious, globally, outnumber priests by more than 200,000. But for two decades, the singular focus of both the media and the Catholic Church when it comes to sexual abuse seems to have been only priests. Two years ago this week, Pope Francis called the world's bishops to Rome to address the failure of the church to protect children against predatory priests and cover-ups by bishops, decades after initial reports about these egregious acts. Before the summit on abuse, leadership groups of both men and women religious issued a joint statement acknowledging that "abuse has taken place in our Congregations and Orders, and in our Church." Meanwhile, those sexually abused by women religious say they have been largely overlooked and ignored. Virtually all of their stories are decades old. It took some of the survivors that long to understand that what had happened to them was, in fact, abuse and not a consensual relationship with a Catholic sister. And once they did, the statute of limitations laws in most states were against them and they did not see the point in going public. That shifted somewhat in 2018. It's not that people hadn't been reporting sexual abuse at the hands of women religious before (they had), but suddenly allegations were showing up in local media with increased frequency. In July 2018, for example, a New York woman accused a Franciscan Sister of Allegany of abusing her with a crucifix when she was 5 years old. In December 2018, a woman in Ohio said a Dominican Sister of Peace molested her after providing refuge from an abusive situation in her home in 1982. In March 2019, a Connecticut man told his local paper that he'd been raped by a Sister of the Holy Family of Nazareth in 1963. Just to name a few. Dispenza credits the uptick to a confluence of the #MeToo movement, which was re-popularized in 2017, with the release of a grand jury report in 2018 that accused more than 300 Pennsylvania priests of sexual abuse. Now armed with the literal language of "me too," survivors of nun abuse — as it's called in SNAP lingo — looked at the Pennsylvania grand jury report, didn't see any women religious among the accused and finally felt empowered to speak up. "Survivors are beginning to say, 'What about me? I'm not on that list; my perpetrator is not there. Why? She's as important as a male perpetrator,' " Dispenza said. Five women spoke to GSR about their sexual abuse at the hands of a woman religious. All of the accused sisters have died — one as recently as last month. Some of the abuse survivors have settled their cases, while others have not attempted any form of litigation. None of them said she has gotten any sense of closure for the rape, both physical and spiritual, that derailed their lives. What they do want, however, is to be heard. Downplayed and dismissed Gleeson's family reported her abuse as soon as they found out. When Gleeson was a sophomore in high school, her mother found the Winnie the Pooh calendar she kept hidden under her mattress that chronicled the details of her so-called relationship. Every meeting. Every sexual encounter. Her parents immediately went to the parish monsignor, Fr. Cornelius Flavin. Dixon V.B. Gleeson, a deeply devout man, cried in the rectory. He'd purposefully placed his five children in a school run by the Sisters of St. Joseph because St. Joseph was the protector of families. How could this have happened to his daughter? Fisher and Gleeson were ordered to stay away from each other. But Gleeson said the police were never called, Fisher remained at Immacolata School and she continued meeting Gleeson in secret until 1977 — almost seven years after the abuse started. The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet declined to comment on Gleeson's case, citing a need to respect the privacy of anyone reporting abuse, but told Global Sisters Report in a recent statement that the congregation was "committed to doing everything within our power to prevent the sexual abuse of minors and to bring healing to those who have been abused." In 2003, Gleeson tried to sue Fisher, the St. Louis Archdiocese and the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, but the 69-year-old Fisher died suddenly in 2004, around the time of her scheduled deposition. At that point, Gleeson, depressed and recovering from a serious accident, settled the case. She did not want to disclose the amount of the settlement to GSR but said it did not even cover her therapy costs. Other abuse survivors told GSR they had similar experiences when they told someone in the church or in a religious community what a Catholic sister had done to them: Their claims were downplayed or dismissed, and the sister in question faced no immediate consequences; if she was ever removed from active ministry, it was not until decades later. Theresa Camden — Detroit, MichiganTheresa Camden told GSR that she and one other woman were discharged without explanation from the Sisters, Home Visitors of Mary novitiate in Detroit in 1972, after they were sexually abused by their novitiate director, Sr. Mary Finn. Finn would invite the two women to weeklong retreats at secluded cottages, telling them they needed to experience nature or the seasons. There, she would sexually violate them — or at least that's what Camden has come to understand. While Camden remembers the years of emotional abuse and manipulation she endured under Finn, she has no memory of the actual sexual abuse due to dissociation, a psychological phenomenon in which victims of sexual trauma can detach themselves from their bodies as a coping mechanism. It's only been in talking with the other woman who Finn abused during these trips that Camden says she came to realize what also happened to her. Camden maintains that all along the rest of the community knew something wasn't right but, by that point, Finn herself was "untouchable." "[She] was beginning to get a lot of fame in the Archdiocese of Detroit," Camden said, noting that Finn was even appointed to be the archdiocesan delegate for religious — the primary liaison between the bishop and local religious communities. "So she was becoming one of the good ol' boys, you know, one of the protected ones." Camden and the other woman, who has remained anonymous, went to Bishop Allen Vigneron with their allegations against Finn in the 1990s. They also brought their allegations to the Home Visitors of Mary. Local media reported that the congregation paid Camden's co-accuser $20,000 (to help cover her therapy costs, the congregation said), but no other action was taken, even as Finn began earning a reputation for being "handsy" at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit where she'd been teaching since 1969. Finn eventually resigned from the seminary in 2019 — the day before local news outlet Deadline Detroit published a story about the abuse allegations against her. In a statement posted by the archdiocese, Finn apologized for using her position of authority to engage in "inappropriate conduct with two adult novices." Vigneron, now archbishop of Detroit, also apologized, saying he had mistakenly believed the situation had already been resolved. Camden's co-accuser died of COVID-19 in May 2020, after which Camden said Finn attempted to call her. "She still [didn't] get it," Camden said. The Home Visitors of Mary have repeatedly declined to comment on the allegations. Finn died in January 2021.

Becky Starr — Milwaukee, Wisconsin

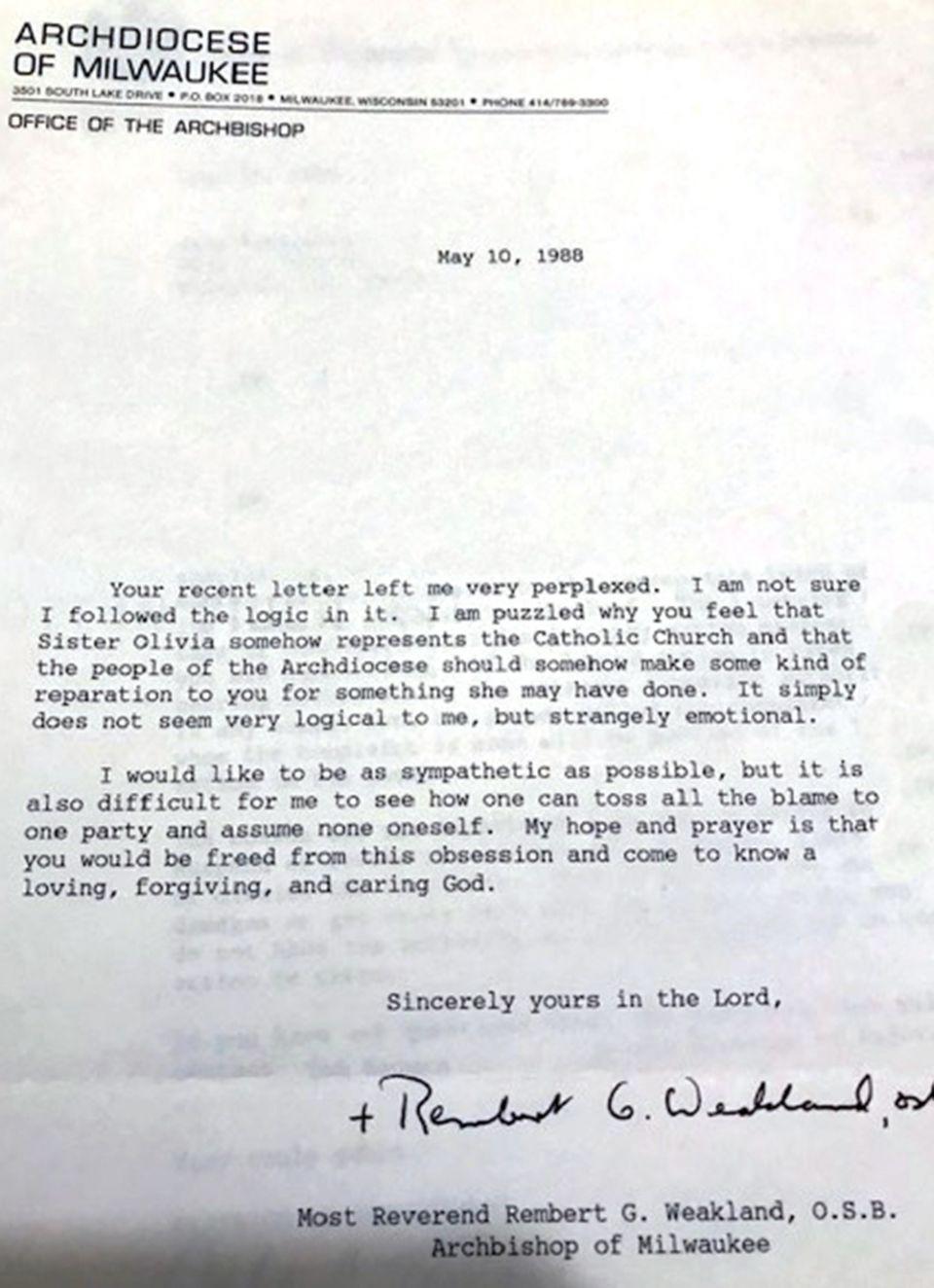

Another woman, who uses the pseudonym Becky Starr to protect her family's privacy, said the School Sisters of Notre Dame refused to even engage with her when she told them she'd been molested by Sr. Mary Olivia Reindl. In 1954, Starr, an enthusiastically religious 13-year-old who used to get up early to sing at Mass every morning before breakfast, was allowed to join the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. But after a decade, she was unhappy and began therapy with Reindl, a psychologist, as she discerned if religious life was right for her. Sometimes, during therapy sessions, Starr said, Reindl would put her hands up the sleeves of Starr's habit and massage her bare shoulders. Years later, after Starr had left the congregation but returned to Reindl's practice, Reindl began removing her own clothes from the waist up during sessions and nursing Starr like a baby. Starr assumed these were normal therapeutic practices. "I know it sounds weird now, but she was a therapist and she had a lot of power over me," she said in an interview. In the 1980s, when Starr finally realized that what Reindl had done to her was sexual abuse, she said she wrote to her former community, asking them to do something. In response, Starr said, she was told that when she left religious life in 1964, she had absolved the congregation of any responsibility for her. The Central Pacific Province of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, which includes the former Milwaukee province, told GSR that they could find no report of abuse or accusations of abuse in Reindl's file and, therefore, could not confirm this claim. Starr also wrote to then Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland and to Pio Laghi, then papal nuncio to the United States. In a written response dated May 10, 1988, Weakland — who was later found to have paid a man $450,000 to stay quiet about their affair — told Starr it was difficult for him to be sympathetic to her when she tossed "all the blame on one party" and assumed none herself. "My hope and prayer is that you would be freed from this obsession and come to know a loving, forgiving, and caring God," Weakland concluded. In his response, Laghi referred Starr back to Weakland. Starr wrote to the state Psychology Examining Board in 1985, which, following an investigation, suspended Reindl's license for a year in 1987 after finding that she had "sexual intimacies" with a patient. That same year, Reindl left her position on the provincial council to become a part-time pastoral minister in the small town of Mazomanie, Wisconsin. The School Sisters of Notre Dame, again, said there is no indication in Reindl's file that she was ever accused of abuse and that she moved to Mazomanie not in response to any accusations but to be closer to her birth family. Reindl died in 2012. "The School Sisters of Notre Dame Central Pacific Province does not tolerate any kind of abuse and takes allegations seriously," they said in an email comment to GSR. "Anyone experiencing harassment, or who knows of potential harassment, are strongly encouraged to file a complaint. … All complaints will be promptly and thoroughly investigated and appropriate disciplinary actions will be taken."

Marya Dantzer — Detroit, Michigan

The sister accused of abuse by Marya Dantzer, Adrian Dominican Sr. Mary Gael, left religious life in 1971, before Dantzer ever reported what happened to her. But that didn't stop Dantzer from trying to sue Mary Gael — then married and known as Gael Biondo — the Adrian Dominicans and the Archdiocese of Detroit in 1995. Thirty years earlier, Dantzer had been a shy, only child from a difficult home environment; she told GSR she did not get along with her adoptive mother, and that her adoptive father, though kind, was a binge drinker. She said Sr. Mary Gael, her freshman English teacher, gave her the connection she craved. Mary Gael mentored Dantzer in poetry and in interpretive reading. She also began kissing and touching Dantzer in sexual ways that became increasingly more invasive, although Dantzer says there was only one instance of sexual penetration — in 1968 when Biondo, who had since been transferred to another high school, organized a field trip to the University of Michigan where Dantzer was then a freshman English major. When Dantzer filed her lawsuit, thought to be one of the first such suits against a Catholic sister, she was drawn into a series of conversations with the Adrian Dominicans that she described as chilling. Ultimately, a lawsuit seemed too expensive and Michigan's statute of limitation laws were not in her favor, so Dantzer settled out of court in 1996. In a statement to GSR, Sr. Patricia Siemen, prioress of the Adrian Dominicans, said the sisters' hearts ached for everyone who suffers sexual abuse. "We are committed to taking every measure possible to prevent such abuse, to investigate and report wrongdoing, and to act justly and compassionately throughout." Biondo died in May 2020.

Cáit Finnegan — Queens, New York

Cáit Finnegan told GSR that Sister of Mercy Sr. Juanita Barto, the jovial Spanish teacher at Mater Christi Diocesan High School* in Queens, New York, molested her regularly over a four-year period, beginning when she was a sophomore in 1966. It started with little notes. Barto would leave them in Finnegan's locker, asking her to come talk in her classroom. She also invited Finnegan to attend Broadway shows with her. The more they talked and developed a "special" friendship, the more Finnegan began to confide in Barto and come to love her like a family member. Soon, Barto started locking the classroom door during their talks and sexually violating Finnegan. Finnegan, an aspiring Sister of Mercy with budding musical talent, said she didn't understand what was happening to her ("In my Irish Catholic family, there was no such thing as sex," she said), but Barto told her that God was love and this was how people expressed love. In 1970, Finnegan tried to join the Sisters of Mercy but was rejected. She said the vocation director told her it was because they suspected she was in an "immoral relationship" with Barto. Furious, Finnegan accused Barto of ruining her life, and Barto never touched her again, she said. The following year, Finnegan was accepted into the community, but she sensed that the other sisters were trying to protect her from Barto. Once, at a vacation house, Finnegan recalls that an older sister swapped her black veil with Finnegan's white novice veil so Finnegan could escape to her room without drawing Barto's attention. Looking back on it as an adult, Finnegan said she isn't sure if the sisters actually suspected sexual abuse or just knew Barto's penchant to develop what she called "obsessions" with people. Regardless, Finnegan was not allowed to make vows at the end of her novitiate, and she never learned why. Barto, however, continued her teaching career until 1988, after which she worked as the assistant manager in a Catholic Charities home on Long Island for people with developmental disabilities. It wasn't until she was an adult that Finnegan came to understand that she had been a victim of pedophilia, but by that time, the statute of limitations in New York had run out. In 2003, the Sisters of Mercy agreed to pay for Finnegan's therapy but denied her requests to meet with Barto. In 2014, Barto died without Finnegan ever having the chance to confront and — as she desired — to forgive her. Two years ago, New York extended the statute of limitations for second- and third-degree rape, and Finnegan considered filing a lawsuit — something she never thought she would live long enough to be able to do. But she said that after a mediation phone call with Sr. Patricia Vetrano, president of the Sisters of Mercy Mid-Atlantic Community, in October 2020, she decided instead to settle with the Sisters of Mercy and the Diocese of Brooklyn.* The Sisters of Mercy declined to comment on the specifics of Finnegan's allegations, although Vetrano said in a recent statement to GSR that the congregation was "deeply saddened by the disturbing allegations of sexual abuse by one of its deceased members from 50 years ago," and that they had established policies and procedures to help prevent sexual abuse. Finnegan said her goal has always been restorative justice — not vengeance — and she is optimistic that Vetrano will make good on her word to work with her in showing other communities of women religious how to model the Gospel when dealing with survivors. It's not enough for them to feel sorry, Finnegan said. "You need to do something about this." Lives derailed When Anne Gleeson surveys her life, she told GSR she can see all the damage from Judy Fisher's abuse. There are the tangible things like medical and therapy bills, and then the more impalpable things like broken relationships and destroyed dreams. To keep her isolated, Gleeson said, Fisher made her drop all of her friends. "I just turned my back on everybody because [she] convinced me that there was something super cool about me — that I was special and I was so mature compared to everyone else," Gleeson said. "We had this thing. It was God's love and no one else could understand." An artist, Gleeson had been awarded a full, four-year scholarship to attend the art program at Avila University in Kansas City; she had spent months in the basement working on her portfolio. But her parents, suspecting Fisher, who was then a principal at a school in Colorado, was trying to lure her away from St. Louis and their protective gaze, refused to let her go. She had to call the admissions office and decline the scholarship. Gleeson was crushed. And because Fisher conflated her molestation with God, it destroyed Gleeson's entire spiritual belief system — which even now, almost 50 years later, leaves Gleeson sobbing so hard in an interview she can barely speak. Losing one's religion is a common result of church-related sexual abuse, said Judi Goodman, a Massachusetts-based therapist who specializes in trauma and treats clergy abuse patients. When an abuser is a religious authority, Goodman explained, the abuse becomes mixed up with the victim's belief that church is a safe place or that God will protect her. So, in addition to the more common psychological responses to sexual abuse — depression, dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder — people abused by clergy or women religious also suffer what can be an isolating crisis of faith. Marya Dantzer said that the emotional and spiritual rape she endured was "more horrific and damaging, by far" than the sexual violation. Gleeson also described what happened to her as "spiritual rape." Of the five survivors who spoke to GSR, none of them still identifies with the Roman Catholicism of their childhood. And only Dantzer, who joined a Unitarian Universalist congregation about eight years ago, and Finnegan, who is a bishop in the Celtic Christian Church, remain connected to any form of organized religion at all. Theresa Camden said she only enters a church building if it's for a wedding or a funeral. "And that's a struggle because the dishonesty in the church is so awful. It's a shame to know the church has totally protected not only the priests, but Sr. Mary Finn in very extraordinary ways," she said. She despises everything Catholic. Several of the women shared that they continue to struggle with intimacy. Camden said she would have loved to have gotten married and raised a family, but being abused destroyed her ability to trust people. Becky Starr, who did get married, said she has no interest in sex as a result of her abuse, which has caused problems in her 53-year-old marriage. Finnegan still has nightmares about Juanita Barto. She also said that after her daughter was born, she was so terrified that someone would hurt her baby that she had to quit her job. She was afraid to leave her with anyone. And she did not return to the workforce until her daughter was in college — and then, only with a therapy dog by her side. But after decades of feeling silenced, some survivors say that, today, they at least feel empowered to speak their truth. In 2018, Starr published her novel A Statute With Limitations: Before #MeToo, a fictionalized account of her abuse. Finnegan has been chronicling her journey from anger to forgiveness on a blog, and in 2019, started abusedbynuns.org to compile resources for other survivors. Additionally, some members of Mary Dispenza's growing list of nun abuse survivors have started a monthly virtual meeting. Participants say this gathering has begun to foster a sense of solidarity for a group of people who have long felt isolated and ignored. Finnegan, for one, has vowed to tell the world about what happened to her. "I will never shut up again," she said. Contact: info@globalsistersreport.org

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.