Dallas Morning News

March 13, 2005

Greg Speers is in prison today on a flawed conviction. The way his case was handled raises questions about fairness in the justice system. Laura Beil tells her cousin's story and how it has made her wary - as a parent and an American.

My cousin Greg Speers lost his life on April 28, 2000. Maybe he will still get it back.

|

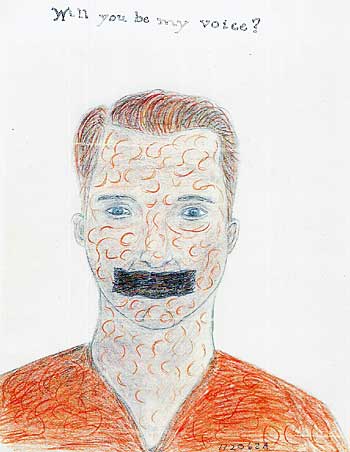

| Photo by Greg Speers / Self Portrait |

The youngest of my Aunt Charlotte and Uncle Bob's eight children, Greg grew up in Tucson, where Uncle Bob was a Walgreens pharmacist. The family would pull up in front of our house in Marshall every other summer, packed into a station wagon brushed with two days of Southwest sand. Those were the Julys of sleeping bags, games of freeze tag, and a slamming back screen door.

Bob and Charlotte Speers presided over the Catholic branch of the family. They were made for children. After their own grew up, they took in foster kids � first Vietnamese refugees, then neglected souls in need of emergency shelter. My aunt and uncle didn't do good deeds because they thought they ought to. They were simply not capable of anything else.

Greg was an engaging, cheery kid who soaked up his role as the baby in the family. The fair-haired adolescent grew into a fetching man, with enviable cheekbones and a Hollywood smile. He stole hearts, then broke them when, in his early 20s, he announced his intention to enter the seminary.

Ultimately, though, he became disillusioned and wanted to reconsider. As a respite, the diocese offered him a job teaching second-graders at a Catholic elementary school in Yuma in 1999. Soon after, an old girlfriend followed him out, and the decision was cinched. He began preparing for the law school entrance exam. He chose to finish the school year in Yuma. He should have realized that national scandals would dictate that an almost-priest should stay far from children.

One student had troubled him almost from the start. I'll call her Stacy. She was a precocious girl who seemed to crave attention from classmates and teachers. And it didn't help that she, like most girls in his class, had a crush on Mr. Speers..

On the afternoon of April 28, 2000, Greg's class was playing a game he called "Math Jeopardy."

One student, hurt that he wasn't calling on her, became disruptive. He told her to go to a cloakroom where kids kept backpacks and supplies. He sometimes sent children there to discipline them, believing that scolding students in front of their peers was unnecessarily humiliating.

Soon after, Stacy joined her friend. He heard the two giggling, saying something about getting naked. Later, as his students played outside, he sent the girls to the principal's office to report their inappropriate talk. He couldn't abandon his class, so he recruited the school's librarian to escort the girls.

If only he had ignored the whole thing.

Assumption of guilt

Just before Greg moved to Yuma, the town had been stunned by reports that a priest who taught at the school in the 1970s had molested his students. The school's current principal was perhaps on a hair trigger from this and other disturbing disclosures of Catholic clergy abuse. In a tragic misunderstanding, the principal thought these girls were coming forward to report an incident on their own and didn't initially realize that Greg had sent them. She dialed the police. They interviewed the girls and eventually arrested Greg.

News that a teacher � Catholic and male � had been jailed on charges of molesting his students hit Yuma like a desert sandstorm. Greg voluntarily consented to a search of his apartment, hoping that if the police realized he had nothing to hide, they would know that they had made a dreadful mistake.

I have to admit that when his sister called to tell me what happened, I wondered about his innocence. Though superficially subscribing to the idea of innocent until proven guilty, we Americans just don't think that way. A mere charge carries an assumption of guilt. Some crimes are radioactive enough to be instant conviction.

You think Greg did it? I asked my husband. How well did I really know him, only seeing him on and off over the years? But from what I could tell, he hadn't seemed creepily fond of children. The only interest I knew he had in anything overtly sexual was something he'd written in seminary about pornography and the language that markets people as objects.

Plus, child predators thrive on manipulation and secrecy, and yet, Greg himself had brought the girls to the principal's attention. The police said Greg had abused girls at school, during class. If Greg wanted to fondle little girls, why did he have an "open classroom" policy that urged parents to drop by at any time? I was never in the school, so I can't say with certainty that Greg is innocent. I can say I question the evidence of his guilt.

Pedophilia can be such a compulsive behavior � that's what frightens me, as a mother of young children. If he had an unnatural attraction to children, why had the police not found signs of such obsession in the apartment where he lived alone? The damning thing was the girls' statements. But an expert on child interviews � secured by Greg's lawyers on the condition that he would state what he found, regardless of whether it helped the defense � would later write a six-page memo detailing everything the officers did wrong. They asked leading questions. They told the girls that "something bad had happened" and that the police needed their help. They didn't make it clear that it was OK to say, "I don't know."

Certain responses were encouraged; others downplayed.

The tales, especially from Stacy, grew wilder each hour: Mr. Speers, for example, had once told her to sneak away and make a naked video of herself. At some point, according to the transcripts, one officer asks whether she isn't telling little white lies.

"Actually, white stands for heaven," she answered. "So I, I would say little red lies."

Another one of her classmates stammered, "I get all confused, and I'm saying all the wrong things."

On the stand

Weeks later, computer forensics finally excavated something incriminating: temporary Internet files, the kind of images that slip silently into your computer with every online surf. They were never saved or printed. Even if Greg could have seen the pictures, and even if they had been real children, they would have been only partially visible for a matter of seconds. Temporary files linger on probably any computer that touches the Internet.

Still, because of two pictures, Greg was convicted in June 2002 on two counts of possession of child pornography.

So in 2003, at the start of his second trial on the molestation charges, he was, at least in the eyes of the legal system, a bona fide child pornographer.

The prosecutors' case rested on the word of the girls. Police interrogations had found five girls who would swear that Greg touched them in places they did not want to be touched. Each girl gave strikingly similar testimony on the stand. Each of the girl's families had sued the Catholic diocese and garnered a handsome settlement � money that might be called into question with a verdict of not guilty.

The only defense Greg could have offered would have been the testimony of experts on child psychology and techniques for interviewing children. Researchers could have pointed out that children can be easily led into providing certain responses, especially to an authority figure. The experts could have testified that the children come to believe the stories they repeat often enough. The psychologists could have said that in some cases like this, hysteria overtakes parents, law enforcement officials and even entire communities.

But the jury never heard these explanations. The judge refused to allow Greg's lawyers to call expert witnesses. His lawyers were left questioning the other teachers, most of whom came to his defense. Other students told jurors that they never noticed anything unusual in the months Greg was reportedly molesting their classmates. The librarian, the closest thing to an eyewitness anyone had, was � and remains � one of his most steadfast defenders. Before that day, she was little more than a professional acquaintance.

Ultimately, the trial came down to the word of adorable, heartbreaking little girls against that of a 31-year-old man, pasty and hollow-eyed from pretrial incarceration.

Greg did profoundly stupid things, too. While out on bail, he took up with a stripper. He felt bitter and rebellious. He had always tried to do the right thing, he told himself, and look where it had gotten him. When the retrieved computer images sent him back to a jail cell, he started writing her letters that became ever more lurid. He was trying to impress her. They were read in excruciating detail in court, one after the other, for days.

The correspondence didn't mention any fantasies involving children. Perhaps the prosecutors were trying to say that anyone who could write such things must be guilty of something.

The jury agreed. My cousin is serving a 105-year sentence.

What is just?

Greg's case has changed us. We fear children we don't know. I drive the baby-sitter home because my husband never wants to be alone with an underage girl. I hesitate to touch my children's classmates, even to pat one on the back. I worry for teachers, everywhere. I worry for kids.

The day Greg was accused, he told jurors, Stacy had approached his desk and to his astonishment asked out of nowhere, "You want me to draw you a picture of sex?" Where could she have come up with such a thing? Where, indeed. Children in our media-saturated culture are steeped in sex. When I was a kid, the raciest thing around was Barbara Eden's bare midriff in I Dream of Jeannie. Now, my daughter could see more suggestive moves during a three-minute Britney Spears video than I saw in an entire season of Capt. Kirk's love scenes. I want my little girl to stay a little girl, but I must battle a world that wants to turn her into a sexual creature as soon as it can.

My family also now has a jaundiced view of the criminal justice system. No longer do we read about arrests with the same vague detachment. We share articles about child accusers who recant. I am struck by the almost universal response of prosecutors: They remain proud of their convictions.

As a parent, I want to believe that child molesters are caught and punished. As an American, I want to believe that the system clears the innocent. I am now unsettled on both counts. Was Greg innocent or guilty? The way his case was treated, the truth may never be known.

If Greg's students were the victims of a crime, they were owed a fair investigation and trial as much as he.

Overturned

In September, an appeals court overturned the computer case, saying, in part, that he should have been allowed expert testimony. That ruling has in turn been appealed, so he waits. If the convictions on the temporary Internet files stand, then we should all be very afraid. Gentlemen, watch your search engines.

Then, two weeks ago, the molestation case was also overturned. Prosecutors are vowing to try again. If that happens, though, the appeals court has made it clear that this time he will be allowed child psychiatrists who will point out that the key evidence against Greg is likely to be nothing but the inadvertent creation of overzealous detectives.

For the better part of five years, Greg has been denied even the simplest pleasantries: sunlight, books, his mother's hand. My Uncle Bob, the man with the most generous heart I have ever known, died after having drained his life savings on his son's legal defense.

In prison, boredom is Greg's biggest foe. Guards seem to view their charges as inanimate objects, not worthy of dignity or simple kindnesses. People who break our laws should be punished, but knowing the things that happen to Greg, I wonder now whether prison is only fostering a generation of angrier criminals. We will see what part of Greg survives for the time, finally, when his life returns.

Laura Beil covers medical issues for The Dallas Morning News. Her e-mail address is lbeil@ dallasnews.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.