Unholy Alliances

By Leslie Bennetts

Vanity Fair

December 1991

[This web version was created from a xerox copy of the original

article (1M file) in the Robert Costello archive. The original article

is also available as two smaller files 1 2.]

Big and sprawling and a bright-yellow

brick, St. Rita's is an imposing presence in a quiet New Orleans neighborhood

of neat little houses and well-tended lawns. It is scarcely past dawn

when the first parishioners begin to file into church for early-morning

Mass, but already the air is as hot as a furnace. Outside St. Rita's,

the force of nature is inescapable: in this tropical climate, lush green

vegetation thrusts into every crevice, floods come with the first hard

rain, and thunder rumbles across the skies in a low, continuous murmur.

Inside the pristine, air-conditioned church, however, an old-fashioned

decorum prevails. Although most of the women wear casual clothes on this

weekday morning, their heads are modestly covered, as if all the years

of liberalization since Vatican II had never happened. As a white-robed

priest leads the faithful in prayer, his voice is mellifluous and soothing:

"And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil,"

he intones solemnly. The faces of his flock are as serene as their sanctuary;

inside this place, man has triumphed over nature to impose a rigorous

order on its darker and more luxuriant excesses.

|

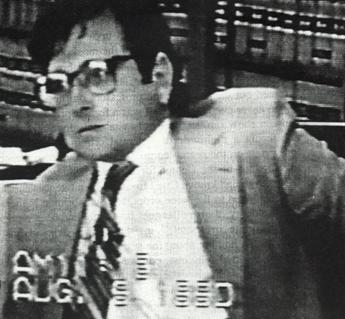

| Former priest Dino Cinel during his deposition in 1990 and some of the child pornography discovered in his room at the rectory. |

|

Or so it seemed until last spring, when the parishioners at St. Rita's finally learned from the news media about the activities of one of their favorite priests. Father Dino Cinel, a charming Italian-born priest who lived at St. Rita's for nearly a decade, was discovered to have stockpiled an enormous cache of commercially produced pornographic films, photographs, and magazines featuring young children as sexual objects. "Little Brother Wants a Kiss!" reads one magazine. "Yes! A minor is loads of fun!" Another shows pictures of children in black leather performing oral sex on each other; one headline advertises "Big Prick Dream Boy." A how-to article entitled "Young Boys Are Fun in Bed" instructs "fellow boy-fuckers" on how to seduce children, from hanging around near schoolyards to striking up conversations—''Be nice"—to initiating sex ("A few drinks or a pipe of hashish ... will help you a lot").

The mere possession of such material carries a mandatory jail sentence in Louisiana, which has one of the strictest child-pornography laws in the nation, but there was more. Also found in Father Cinel's room were 160 hours of homemade pornographic videotapes in which the handsome priest performed anal sex, oral sex, group sex, and a dizzying array of other diversions (often including his fluffy white lapdog) with at least seven different teenage boys. His voice as soft as a caress, he was relentlessly persuasive as he urged one boy to have sex with his brother on-camera, another to have intercourse with his mother and to bring in his sister and her boyfriend to make a group-sex video they might sell in Denmark. At one point one of Cinel's partners reported back on his mother's reaction when he tried to seduce her: "She got real upset," he said plaintively. "She never reacted the same to me after that. It blew her mind."

Hers wasn't the only mind that was blown. To the horror of the parishioners at St. Rita's, many of the videotapes were made in the rectory, in Father Cinel's modest little suite of rooms right under the noses of the other priests in residence there. But the uproar last spring was only the public eruption of a scandal that the church had kept secret for more than two years and that was finally revealed not by diocesan officials but by Richard Angelico, an outstanding investigative reporter on WDSU-TV, the local NBC affiliate. Father Cinel's cache of contraband had been discovered at the end of December 1988, and although he himself was discreetly ousted as a parish priest shortly thereafter, the archdiocese held on to his collection of pornography for three months before turning it over to the district attorney's office, prompting a barrage of later questions about whether the tapes had during that time been purged of sequences involving minors or parishioners. In addition to the resulting charges of a church cover-up, when the news became public the district attorney immediately came under fire for his failure to prosecute Cinel.

The Catholic Church

is in crisis over the shocking incidence of pedophilia in the priesthood—its

lawsuit payouts could total $1 billion within the next few years.

But how is the church confronting the problem? Leslie Bennetts reports

on the case of a New Orleans priest who allegedly exploited young

men for sex and collected child pornography, but was allowed to

re-emerge as a tenured college professor in New York. |

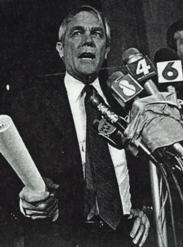

Harry Connick Sr., the father of the singer, is a devout Catholic and a parishioner at St. Rita's as well as the longtime D.A. of Orleans Parish, New Orleans being a town so Catholic its counties are called parishes. Although Connick had lobbied hard for Louisiana's tough new child-pornography statute, he had also entertained Father Cinel in his home, and the sociable priest had even performed the rites at the wedding of Connick's brother-in-law. In a television interview with Angelico, the D.A. admitted that one reason he hadn't prosecuted the case, despite a recommendation by his own investigators that he do so, was his unwillingness to embarrass "Holy Mother the Church." The ensuing outcry drove him from public view, although the D.A.'s office did finally file a single, unspecific charge of possession of pornography against Cinel—a move so halfhearted that it elicited still more criticism, since hundreds of charges could technically have been filed based on the commercial pornography collection alone.

Indeed, the Cinel case is being described as the largest documented case of priest pedophilia in the history of the crime. Federal authorities are expected to file additional charges this fall based on violations of customs and postal regulations, since Cinel admitted he had smuggled some of his stash into the country from Europe. Then there are the civil lawsuits: two so far, one by each of Cinel's most long-standing boyfriends, citing not only the priest but also the church for its failure to protect them from Father Cinel's predations.

A major New York educational system has also become embroiled in the controversy. After being quietly dismissed from St. Rita's in early 1989, Cinel, a respected historian, continued to teach at Tulane University a few blocks away, and before the next year was out he had landed a job as "distinguished professor" of history at the College of Staten Island, which is part of the City University of New York. The distinguished-professor rank carries a $20,000 bonus, so by last winter Cinel was ensconced at Staten Island in the cushiest of academic posts, with an annual salary of $90,000 and a decidedly underwhelming work load of half a course per semester. The new distinguished professor was given tenure, of course, so when the scandal broke shortly thereafter, the College of Staten Island found, to its extreme dismay, that it couldn't even suspend Cinel without running a lengthy procedural gauntlet of byzantine complexity, a process that would obviously take months to complete and in which Cinel was entitled to an automatic defense by the union representing faculty members. In September, the college finally reassigned Cinel to a theretofore nonexistent position at CUNY Press, a largely nonexistent entity that has yet to publish a book. "The highest priority is to avoid contact between him and students," said Dr. Barry Bressler, the vice president for academic affairs at the College of Staten Island. The college had originally settled upon Cinel after a long search process ratified by some of the most prominent historians in the country, but after the scandal broke the school was besieged with criticism for its handling of the situation; it turned out that most of the professors on the search committee never even knew Cinel was a former priest—a fact he had somehow omitted from his vita—let alone a disgraced one facing a multitude of potential criminal charges. The lone priest on the search committee—Lydio Tomasi, executive director of the Center for Migration Studies on Staten Island, who had known Cinel for more than twenty years and even belonged to the same order, the Scalabrinian Fathers—never told any of his colleagues that Cinel had been a priest. "It was quite irrelevant," insists Tomasi, who claims to have known nothing about the sex scandal.

|

| Cinel with his wife, Linda, and teaching at the College of Staten Island last May. |

|

With assorted religious, educational, and criminal-justice systems reeling in his wake, the fifty-year-old Cinel has been living in Brooklyn since last summer with Linda Pollock, the fellow Tulane history professor he married two years ago after getting her pregnant, and with their toddler, a girl. The Scottish-born Pollock is "kind of a wallflower," according to Dr. Bressler. "She's the opposite of Dino." Indeed, even his enemies acknowledge that Cinel is extremely charming. He is now presenting himself as a respectable family man while maintaining a posture of aggrieved innocence, telling everyone who will listen that his sexual peccadilloes are behind him and that he can't understand why everyone is making such a big deal out of something that happened in the past. "Before this I was a prince—now I'm a pariah," he said bitterly to another professor over the summer.

He may be a pariah, but he's also free to walk the streets, and the mere thought makes many observers shudder. "Somebody's got to put this guy in jail," says Gary Raymond, a private investigator and former New Orleans policeman who has worked on the case. "The experts always say there's no cure for pedophilia, and based on the lack of proof of rehabilitation other than Cinel's saying 'I've given it up,' I can only assume that what he's doing at the present time is molesting kids, because that's what Dino Cinel has always done, and everything else—the priesthood, Tulane, CUNY—everything has been secondary. If he's photographed seven boys, he's seduced seventy, and if he's seduced seventy, he's taken a shot at seven hundred."

Unfortunately, such numbers would not be unprecedented; in the last few years, the Catholic Church has been overwhelmed with similar cases. In fact, it is surprising that Cinel's own archdiocese handled his case so ineptly, since it had already endured a horrific embarrassment a few years earlier with a slew of lawsuits against Gilbert Gauthe, a Louisiana priest who has thus far cost the church more than $20 million. "According to some of the estimates, as many as two hundred kids, mostly altar boys, were abused over a five- to seven-year period," says Raul Bencomo, an attorney for some of the plaintiffs. The damage was exacerbated by the fact that church authorities had known Gauthe was a pedophile. "They shuffled him from one parish to another and swept it under the rug to avoid the embarrassment," says Bencomo. "They have their own code of silence, just like cops, but there's no question there were other priests involved. These guys were trading these kids like baseball cards." A total of seven priests were eventually implicated in the scandal, and Gauthe is currently serving twenty years at hard labor.

"The Cinel case

is a Watergate kind of story, because ultimately every one of these

cases is a tragedy." |

According to the experts, such situations are all too common. "The pattern you find in many if not most of these cases is that a priest is removed and recycled, sometimes with therapy, sometimes not," says Jason Berry, a Catholic journalist and the author of And Lead Us Not into Temptation, a book about homosexuality and pedophilia in the priesthood that will be published next year by Doubleday. "They're placed in another parish, in another priestly assignment, and when parents and parishioners find out they have received damaged goods, they get very angry. "

Increasingly, they also get a very expensive form of revenge. "Roughly $300 million has been paid by church officials and insurers since 1985 in cases of priests abusing children and adolescents," reports Berry, adding that there have been at least two hundred priests or brothers reported to the Vatican Embassy for such offenses in the last six years alone. Since many court records are sealed and settlements are often predicated on the enforced silence of the plaintiffs, such estimates are generally conceded to be extremely conservative; internal church documents describe priest pedophilia as a major crisis and warn that lawsuits may cost the church as much as $1 billion by 1995. No one really knows how many child molesters there are in the general population, let alone the priesthood, but around 6 percent of priests are believed to be pedophiles, according to A. W. Richard Sipe, a former Benedictine monk and the author of A Secret World: Sexuality and the Search for Celibacy.

Catholic officials who deal with pedophilia object to its characterization as a particular problem for the priesthood. "I don't think it's a church problem, I think it's a universal problem," says Monsignor Robert Bacher, president and C.E.O. of St. Luke Institute, a psychiatric hospital in Maryland whose patients include priests with sexual disorders. "Most of the people we treat who are pedophiles were abused by their own families, and it grows in geometric progression—a father abuses three or four children, and they go out and become child abusers."

Nevertheless, other analysts find the church particularly culpable in how it handles the problem. "What is so staggering to me is not that there are a lot of pedophile priests, because child molestation affects all layers of society," says Jason Berry. "What staggers me is the stupidity of the bishops who simply are afraid to do the morally correct thing. The Cinel case is a Watergate kind of story, because ultimately every one of these cases is a tragedy. You have the hubris of power—the raw arrogance, the blindness, the myopia. Every one of these stories is about the abuse of ecclesiastical power, and about the ecclesiastical power structure trying to conceal the internal corruptions that have long been tolerated."

How long Dino Cinel's corruptions had been tolerated remains a matter of conjecture. Philip Hannan, the New Orleans archbishop during Cinel's tenure at St. Rita's, maintains that Cinel arrived there with glowing recommendations from his former bishop in California. However, Chris Fontaine, one of the two young men now suing Cinel, told WDSU's Richard Angelico that the priest once admitted to him that he was fleeing from earlier indiscretions. "He got into some serious trouble in New York, and he went to California, and then he got into some trouble in California and he got kicked out of the church ... because he was having homosexual problems and they told him to get out," says Fontaine. In New Orleans. Cinel "started all over again," Fontaine adds. Through his lawyer, Arthur "Buddy" Lemann, Cinel categorically denies Fontaine's account. When I ask Hannan, who has since retired as archbishop, if he knew anything about such a history, he says, "That is absolutely not the story of the church."

Even if the church knew nothing about Cinel's proclivities, experts report that such discreet recycling is common. "I've followed priests who have had this problem who have been in dozens of parishes all over the country," says A. W. Richard Sipe. "The policy is 'Avoid scandal at any cost.'"

For Fontaine and Ronnie Tichenor, the other young man who has filed suit against Cinel, the knowledge that theirs are not isolated cases provides little consolation. Both are now in their mid-twenties, both are the products of troubled family backgrounds, both lacked a stable father figure at home, and both remain deeply disturbed by their experiences with Father Cinel. Tichenor says he was only thirteen when he began having sex with the priest (Cinel claims he doesn't remember how old Tichenor was when they got involved), but the passage of years has done little to assuage his turmoil. "Many's the night I sat in the kitchen of my mother's house with the barrel of a gun in my mouth," Tichenor told Richard Angelico.

The D.A. admitted that

one reason he hadn't prosecuted the case was his unwillingness to

embarrass "Holy Mother the Church." |

Fontaine acknowledges that he was seventeen when his affair with Cinel started, but he has always looked far younger than his years, and his mental capabilities are limited; indeed, he is described by his lawyers as borderline retarded. Cinel's videotapes provide eloquent testimony to Fontaine's childishness; in one sequence, he is watching a Smurf cartoon on television while Cinel performs oral sex on him. Fontaine remains particularly fragile; he has been diagnosed in the past as both suicidal and, after threatening to kill Cinel, homicidal, and he is haunted by his feelings of betrayal by the priest, to whom he had been deeply attached. Fontaine finally decided to sue only after seeing an issue of a European porno magazine entitled Dreamboy U.S.A., which consisted entirely of pictures of himself—posing in provocative positions, pulling down his underpants, displaying his erections, masturbating—secretly supplied to the magazine by Cinel. Cinel claims he never got any money for the pictures—but for Fontaine, who believes that Cinel sold the material without telling him, the discovery was the ultimate blow in a series of disillusionments made possible by his own terrible vulnerability.

A slight, freckled young man with reddish-brown hair, Fontaine speaks slowly and haltingly, stumbling over syntax and groping for words; he may not be articulate, but after years of therapy he has come to a clear understanding of why Father Cinel was able to manipulate him so egregiously. "I was just begging for somebody to love me," Fontaine told Richard Angelico, his voice suffused with bitterness. "He made me believe he loved me and he would always be there for me. My parents didn't care about me, and I didn't have nothing. If he had told me to jump off a bridge, I would have jumped.... He made me believe that I was a kid in need of a father and he was a father in need of a son, and God put us together to help each other and to serve each other's needs. I was seventeen years old, but I must have been fourteen years old in my brain.... I didn't think about the cost. All I knew was here was a person telling me he loved me, and I was going to do everything in my power to keep him.... When I was with him, I really didn't doubt his word. All I knew was that for the first time in my life I had somebody home waiting for me that was supposedly going to be there forever for me.... I sat outside that church many a night in the pouring rain, waiting for him to come home, where I could go inside. That's how much I loved him."

A cluster of television cameras and reporters are massed in front of Darryl Tschirn's law office overlooking Lake Pontchartrain as Dino Cinel and his attorney step off the elevator. Cinel's lawyer is scowling as they dart through the assembled press, but the former priest simply looks shell-shocked, his eyes wide and startled like those of a deer caught in headlights. Pale and wan, clad in a pin-striped navy suit jacket over rumpled khaki pants, he keeps his head down as he disappears into the inner office, where he is about to give a deposition in one of the two civil suits that have been filed by Tschirn and David Paddison, the attorneys for both Fontaine and Tichenor. On this particular occasion, Cinel spends a lot of time pleading the Fifth Amendment, but it doesn't matter; he has already aired a remarkable amount of dirty laundry in a videotaped deposition taken in August of 1990. If Cinel looks somewhat chastened now, back then he seemed a different man entirely—arrogant to the point of insolence, cavalier, even nonchalant as he discussed his richly varied sex life with both men and women during his twenty-three years as a priest, his illicit activities in the rectory at St. Rita's, and his contraband pornography collection, among other topics.

According to his deposition, Cinel, the youngest of nine children, was first introduced to sex back home in Italy by the headmaster of his boarding school, whom he described as "an eminent priest who was a friend of the pope." Cinel was thirteen or fourteen at the time, and the encounters with his superior continued over the next couple of years. After Cinel became a priest, his sex partners included both women and young men; after acquiring a master's degree at New York University, he earned his doctorate at Stanford, maintaining a four-year affair with a woman in California in addition to his more fleeting homosexual contacts. Cinel's taste for adolescent boys was already well established; when he moved to New Orleans, he made a point of calling the D.A.'s office to ascertain the age of consent in Louisiana. He had been down to the French Quarter, where many male hustlers hang out, "and I had seen that some of them looked young and I wanted to know what the situation was here," Cinel explained. "I tried to stay clear of the law." At no point during his entire four-hour deposition did he mention the conflict between his behavior and his vows as a priest. Sparring verbally with the lawyer who was questioning him, Cinel taunted his opponent as if he thought he were invulnerable, and a mocking smile rarely left his face. Cinel's lawyer, Arthur Lemann, has a ready explanation for his client's attitude back then. "He had been assured he wasn't going to be criminally prosecuted and that the deposition he was giving would be confidential and sealed," says Lemann, a sleek, portly man who favors three-piece white linen suits, saddle shoes, Panama hats, and fat cigars. "The D.A. had agreed not to prosecute him; there was a binding oral agreement."

The beleaguered district attorney refuses to comment on this or any other aspect of the Cinel case, which has been a major headache ever since Connick admitted he went easy on Cinel because he didn't want to embarrass the church. "It's a pending case, and I'm not going to discuss anything about it," Connick tells me. Even things he's said in the past? He groans. "Especially things I've said in the past," he says.

|

| New Orleans D.A. Harry Connick Sr. [below] and former New Orleans archbishop Philip Hannan, one of the first to be informed of Cinel's activities. |

|

However, Cinel isn't the only one who got the distinct impression that Connick didn't want to prosecute him. Gary Raymond, who worked as an investigator in the D.A.'s office for seven years before retiring to establish a private practice, wrote Connick a three-page letter in the summer of 1990 outlining the case against Cinel. "I literally begged Harry Connick to charge this man," says Raymond, a wiry, intense man who is determined to see the former priest brought to justice. "I was then told by an investigator in the D.A.'s office that Connick was upset because I had created a paper trail. " Connick still took no action; months later, Raymond ran into him on St. Patrick's Day. "When are you going to prosecute this priest?" he demanded. "Never, as long as I'm D.A.," Connick replied, according to Raymond. (It was only after the media broke the story last spring that Connick even filed the one charge against Cinel. After months of continuing criticism, this fall the D.A. finally charged him with sixty separate counts of possession of child pornography.)

The alleged agreement with the D.A. isn't the only deal Cinel claims to have made: when another priest finally blew the whistle on him, Cinel says, the archbishop agreed that if he departed quietly the material discovered in his room would not be used against him. The circumstances of Cinel's downfall were ironic. He had just been driven to the airport by Linda Pollock, his future wife, who was to use his car while he made a lecture trip to Italy. She promptly locked the keys in the car and called the rectory to ask another priest to check Cinel's room for an extra set. Father James Tarantino began poking around in Cinel's desk, where he found piles of child pornography. Archbishop Hannan was notified and called Cinel in Italy the next day. Both Cinel and Hannan agree that the archbishop's first request was that the errant father simply stay in Italy; Hannan doesn't seem to see anything wrong with having encouraged a priest who had just been discovered to have committed criminal acts to become a fugitive from justice. But Cinel refused to disappear. "He replied, to my great surprise, that he resented the invasion of privacy of his room, and didn't show any kind of remorse," Hannan reports. The rest of their conversation is a matter of bitter dispute. "Of course I did not make any deal at all," protests Hannan. "Those charges are ridiculous." Indeed, Hannan has repeatedly expressed outrage that anyone would even question his word against that of someone like Cinel. "Father Dino was a real number-one con man," he says indignantly.

However, Hannan's version of events is contradicted by others as well. One key issue is whether the archdiocese notified Tulane University when the tapes were discovered. The first time I ask Hannan whether he told Tulane, he stammers and hedges. "I'm trying to think ... I don't remember what we did about Tulane," he says. Half an hour later, his memory suddenly improves, and he calls me back with a new answer, saying that he had indeed informed the school. "It was all done within twenty-four hours," he says briskly. "I took care of notifying some of the people, and Bishop Muench notified some of the others—right away."

Tulane has a different story. Strangely, the university has also assumed an embattled posture, with top officials refusing to answer any questions about Cinel, but in response to my repeated inquiries the school's Office of Public Affairs finally read me this statement, approved by the president: "The archdiocese did not inform the university of the allegations made against Dino Cinel prior to the news reports about him." Although it would appear that either former archbishop Hannan or the university's president must be lying, even Tulane faculty members are puzzled. According to one professor, the history department received a directive from the dean more than two years ago that they were to respond "No comment" to any questions about Cinel from the media. If university officials didn't know anything, what were they instructing faculty members to stonewall the press about? In any case, Tulane later said nothing to the College of Staten Island about any problems involving Cinel.

Further questions have been raised about the archdiocese's dealings with St. Rita's. "Parishioners were never told about what happened in the rectory, nor were they ever asked to speak with their children," reported Richard Angelico on WDSU-TV. Don Richard, an attorney for the archdiocese, admitted to Angelico that this was true, and tried to justify the church's silence in terms of its sensitivity to a possible criminal investigation: "My advice to the church was 'You do nothing to prejudice a criminal case that might arise against anyone'—and so we did absolutely nothing," Richard explained.

A couple of months later, however, when I ask former archbishop Hannan about it, he suddenly changes the official story, thereby contradicting his archdiocese's own lawyer. "As soon as he knew about this, Father Tarantino told the people and apologized to the people," Hannan maintains. "He didn't even wait for a Sunday; I think he told them at a weekday Mass so they would know immediately."

Another question is why the church didn't insist Cinel get some kind of treatment. "Dino flounced out on us," says Hannan. "He left angry, and we had no knowledge of where he had gone." In fact, Cinel could rather easily be found a few blocks away, in his longtime office at the Tulane history department. But perhaps the most important controversy involves the church's decision to hang on to Cinel's pornography collection for three months before turning it over to the authorities. Even then, the archdiocese made its squeamishness about prosecution more than apparent. "We therefore wish to make it clear that it was not the intention of the Archdiocese in taking such action that it would be regarded as seeking to initiate or urge prosecution of Dr. Cinel or anyone else thereby," wrote Thomas Rayer, an attorney for the archdiocese, in a letter to the D.A.'s office. "This action on the part of the Archdiocese should therefore not be considered by your office as in any way seeking the initiation of criminal charges with respect to this material or any activities of Dr. Cinel in relation thereto." Judging by his subsequent inaction, the district attorney got the message.

Many wonder if the evidence was tampered with while in the hands of church officials, but Hannan denies there was any purge of the material, saying the church kept it for so long merely to "get some idea of who was involved" on the videotapes. Others are less than convinced. "This is a classic story of a church coverup," says Jason Berry. "I think the archbishop and the lawyers for the archdiocese broke the law. You don't sit for three months on child pornography; possession of it is a crime.... Dino Cinel should have been arrested the moment he got back from Italy." According to a recent deposition by Bishop Robert Muench, the tapes remained at St. Rita's for six days after Father Tarantino found them, before they were even turned over to the archdiocese. "I think in those six days Tarantino blasted through those tapes to see who was there and who shouldn't be there," says attorney Darryl Tschirn. "Nobody ever inventoried the tapes. Nobody knows how many there were—and how many they ended up with." Bishop Muench admitted in his deposition that he and Tarantino fast-forwarded through some of the tapes to see who was on them, but Tarantino says, "The materials I found were turned over to the archdiocesan representative precisely as found without exception."

But if there was a cover-up, it wouldn't surprise some who have dealt with pedophiles in the church. Louisiana attorney F. Ray Mouton served as the lawyer for the notorious Father Gauthe, and he also co-authored a confidential report to the American bishops on priest pedophilia in 1985. Last spring, Mouton was asked by a Washington, D.C., television station, WUSA, how often the Catholic Church tries to obstruct criminal investigations and cover up incidents of priestly pedophilia. "Always," Mouton said flatly. "They may put forth an appearance of cooperation, but in the back room in the chancery, they're designing a plan to stonewall."

David Figueroa was only five years old back in 1964 when, he says, Father Joseph Henry, the pastor at the Church of St. Anthony in Kailua, Hawaii, began to abuse him sexually. One of fourteen children in a devout Catholic family, Figueroa attended the St. Anthony Parochial School, and his mother worked as a housekeeper at the church rectory, one of several places where he says he was routinely molested by his priest during the next eight years. When the pastor died in 1972, he was replaced by Joseph Ferrario, who is now the bishop of Honolulu. Figueroa says he confided in Ferrario that he had been sexually exploited by Father Henry for years, whereupon Ferrario embarked on what was supposed to be counseling. Instead, according to Figueroa, the priest began his own sexual relationship with the boy, which would continue for the next ten years. When he was nineteen, Figueroa began to receive counseling from Father Tony Bolger, another diocesan priest, but before long Bolger too had instigated what Figueroa says was a sexual relationship. The teenager told Ferrario, who allegedly continued to molest him as well, about his experiences with Bolger, but instead of taking any punitive action, Ferrario appointed Bolger as pastor at St. Anthony. By this time Ferrario himself had become a bishop. It wasn't until 1985, more than twenty years after the whole saga had begun, that David Figueroa's mother learned about the alleged sexual exploitation and reported it in a letter to Archbishop Pio Laghi, then the papal pro-nuncio in Washington, D.C. Ferrario defended himself by saying that an investigation had been conducted by the church and that the accusation was unfounded. However, David Figueroa was just getting started. In 1989 he publicly announced his charges of sexual molestation against Bishop Ferrario, who again denied everything and dismissed Figueroa as a "good storyteller." Last August, the young man finally filed a civil lawsuit against the bishop.

Although Ferrario is the first member of the U.S. hierarchy to face such charges, another North American bishop has already been brought down by a pedophilia scandal. Last year Newfoundland's Archbishop Alphonsus Penney resigned in disgrace after an investigative panel he himself had established condemned his handling of widespread sex abuse at a Catholic-run boys' orphanage. The commission found that priests who abused boys sexually were better treated by the hierarchy than were the victims, and said that the lack of archdiocesan leadership might actually have encouraged the abuse. Archbishop Penney, who had resisted earlier calls for his resignation, finally took responsibility for the church's failure to act on long-standing reports of molestation. "We are naked," said Penney. "Our anger, our pain, our anguish, our shame, and our vulnerability are clear to the whole world."

That scandal was only one of many that have stunned Newfoundland's Catholic community in the last couple of years. More than two dozen priests and Christian Brothers have been convicted of or are facing charges of sexually abusing boys, and the moral verdicts have been even harsher than the criminal ones. Last August a Newfoundland judge told Edward English of the Christian Brothers, "You are a disgrace to the order and to humanity," and sentenced him to twelve years in prison. While Canada has been rocked by its epidemic of priest pedophilia, it doesn't compare with what is going on in the United States, where the cases have been multiplying faster than anyone can count. Not that church officials particularly want to; the Catholic Church insists that it has no central reporting system and therefore no figures on the extent of priest pedophilia around the country. "We have no way of knowing for sure how many cases or complaints are out there," says Mark Chopko, general counsel to the U.S. Catholic Conference, the public-policy arm of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops. Chopko, who is also the author of a 1988 statement on priest pedophilia that remains the last official pronouncement on the subject, admits that the situation got so bad that by the mid-1980s the church was totally unable to obtain liability insurance covering sex abuse, although he claims that such coverage is gradually becoming available again. But despite the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in punitive and compensatory damages, the official church position continues to be that its pedophilia problem is no worse than anyone else's. "I don't think it's a crisis for the priesthood," says Chopko. "I think it's a problem for all institutions, like churches, that have to care for children. It's a problem for schools, for child-care agencies, for scouting agencies, for day-care centers—and it's a problem for the clergy." Chopko rejects as "utter and complete nonsense" the idea that the church frequently tries to cover up the problem. "I can't tell you that every time one of these charges has been filed it's been handled with an adequate degree of charity or the right degree of promptness," he says, "but, knowing many of the bishops and clergy involved in some of these cases, either they didn't know what was happening or they didn't believe anything so horrific could be happening in one of their institutions."

Courts around the country are increasingly finding otherwise as a massive amount of documentation accumulates on efforts by church officials to conceal incidents of child molestation and a widespread pattern of gross insensitivity to the suffering of victims. Last December, a Minnesota jury awarded $3.5 million, including $2.7 million in punitive damages, to a young man who had been sexually molested for eight years, starting when he was a thirteen-year-old altar boy, by a priest with a long history of such abuse. According to Father Thomas Adamson, he began molesting boys in 1961, in his first parish assignment, and he admitted such transgressions to his bishop three years later. The bishop told him to control his behavior and transferred him to another parish. For the next twenty-three years, Father Adamson continued to be reassigned to different parishes despite ongoing complaints and at least three interludes of psychiatric treatment at different facilities. Internal church documents reveal a great deal of hand-wringing about the problem and a constant concern that the scandal might become public, but no decisive action by church officials to ensure that Father Adamson would no longer be in a position to molest youngsters. "They knew about this guy and they didn't report it, so he never got prosecuted, and now he can't be, because of the passage of time," says Jeffrey Anderson, a St. Paul attorney who is representing Adamson's victims in eleven different civil lawsuits. "Father Adamson sexually abused at least thirty-five boys we've identified in various parishes, but he's never spent a day in jail."

Anderson, who is also the attorney for David Figueroa, is currently handling more than eighty cases involving priest pedophiles around the country. The often repeated figure of two hundred priests reported for sexual misconduct in the last six years is a gross underestimate, according to Anderson, who says he personally knows of well over two hundred and the total figure "has got to be over four hundred." At least half of the cases he himself has dealt with involve some kind of church cover-up, he adds. "The pattern is one of institutional indifference and complicity to misconduct," he says. "Even if the church has reason to know it's going on, there's a head-in-the-sand kind of attitude—and when they do discover it, then there's a pattern of conspiracy to conceal it and avoid any public scandal or scrutiny."

As in the Adamson case, the expiration of the statute of limitations has often worked in the church's favor in precluding criminal prosecution when past abuse finally does surface. However, in some states the church has a more powerful ally in the so-called doctrine of charitable immunity, which bars lawsuits against charitable institutions. This law has been upheld under even the most tragic circumstances, as in the case of Christopher Schultz, a New Jersey boy who was abused from the age of ten by Edmund Coakeley, a Franciscan brother who was a parochial-school teacher and a scoutmaster. Schultz's brother was also molested by Coakeley, whose taste included bondage and sadomasochism: "He would take pictures of them doing what he'd tell them were the Stations of the Cross," says David Jaroslawicz, the attorney who eventually filed suit on behalf of the Schultz family. Christopher Schultz became increasingly disturbed, and when his parents finally learned about the abuse, they went to the church and asked for help. "The church denied anything happened, and said the child fabricated everything," says Jaroslawicz. Christopher finally committed suicide in 1979. "He ingested wintergreen tablets from the medicine cabinet and said, in essence, 'I can't live anymore with what I've done,'" says Jaroslawicz. "The real outrage here is the cover-up. This child probably wouldn't have killed himself if these people had acknowledged that the child hadn't done anything wrong and had been taken advantage of. The fact that they made him feel that nobody believed him, and that he had to go to school every day and see this guy—that totally shattered the child." It shattered his family as well; his mother, a nurse, had a nervous breakdown, according to court papers, and the parents were later divorced. The family's subsequent lawsuit was vigorously fought by the Archdiocese of Newark, the Franciscan Brothers, and the Boy Scouts of America, who demanded it be "thrown out on the grounds that charities are immune from paying damages to beneficiaries of their services in New Jersey," according to the Asbury Park Press. In 1984 the New Jersey Supreme Court agreed, dismissing all claims by the Schultz family.

Representatives of the church now acknowledge that mistakes have been made, but they claim that the church has changed in recent years. "We have been trying harder, and we've been generally doing better," says Mark Chopko of the U.S. Catholic Conference. "If you look at the cases that are filed now, it's not new incidents as much as it is abuse that happened in the 1960s and '70s." Chopko vehemently denies that cover-ups are still occurring. Police officials in two Virginia counties have recently offered a different point of view. Earlier this year, Father Thomas Chleboski was arrested in Arlington and charged with six counts of molesting a thirteen-year-old student at Our Lady of Victory School. "Police say they received a complete lack of cooperation from the Roman Catholic Church," reported Washington's WUSA-TV. Indeed, according to Detective Tom Bell of the Arlington County Police, when detectives first contacted church officials, "they would not even acknowledge that this man was a priest," let alone give the police any information on where to find Father Chleboski. An investigation revealed earlier alleged incidents of abuse at previous places Chleboski had served, but there too detectives were given the cold shoulder by church officials. "The individuals told us that they were told by the archdiocese not to say anything to the police," said Detective Gary Costello of the Montgomery County Police Pedophilia Unit.

Asked about the Chleboski case, Mark Chopko says the lack of cooperation was due solely to the archdiocese's administrative desire to centralize communications and make sure any statements came from the chancery rather than from individual parishes. "Conspiracy to me connotes some intention not to tell the truth and not to deal honestly with a known situation," Chopko says. "The idea that there has been some kind of intention to deal dishonestly with reports of child abuse is just nonsense. "

On a drowsy afternoon in high summer, New Orleans's Jackson Square is quiet and picturesque. Just beyond a line of horse-drawn carriages, the plantain fronds rustle faintly in the ghost of a breeze off the Mississippi River, a saxophone wails plaintively in the hands of a street musician, and a sidewalk artist draws pictures for the passing tourists who flock to this quaint landmark in the middle of the French Quarter, where the dignified spires of St. Louis Cathedral tower over the lacy wrought-iron balconies that ring the square. Chris Fontaine's father used to work the crowds here as a sidewalk artist, and it was here that Chris says he first met Dino Cinel, on a day when he was upset about family problems and particularly vulnerable to the attentions of a sympathetic stranger. "He came walking up to me ... and he started telling me he was a priest," Fontaine reported in a taped interview with Richard Angelico. "We became friends." According to Fontaine, they didn't have sex until they had seen each other two or three times, whereupon Cinel "asked me if I smoked weed, and asked me if I knew how to roll." After they had smoked some marijuana, Fontaine said, "he just reached over and started rubbing his hands on me and told me he wanted to give me a massage. ... Then he told me to take off my clothes. He just told me to leave my underwear on, and it went from there. He started masturbating me, and I tried to get away; he held me down for a minute and told me, 'Just relax and close your eyes.' He put it in my head that they did it in Greek days and it's all right."

Cinel has provided a markedly different account of these events. He claims that he picked up Fontaine several blocks away from Jackson Square at the corner of Bourbon and St. Ann, a notorious hangout for male prostitutes, and that Fontaine was an experienced hustler. "He approached me and asked me first if I was a policeman," Cinel said in his 1990 deposition. "He was afraid I was there to bust him, because it was obvious what he was doing.... He said, 'Do you want to have a good time?'" Cinel admitted that Fontaine looked "very young ... probably fourteen, fifteen years of age," and said that the boy showed him an ID to prove he was seventeen. At the time, Cinel was forty-one.

Both Fontaine and Cinel agree that the boy went on to become a regular visitor to the rectory at St. Rita's. Indeed, Fontaine says he lived there off and on for six to nine months, lounging in the common room, where he watched television with the other priests, and spending the night and waking up to the housekeepers, who routinely found him in Cinel's bed in the morning. Former archbishop Hannan admits that other priests at St. Rita's were aware of such comings and goings, but Cinel apparently told them that the teenagers who frequented his room were homeless boys whom he was counseling. Still, it is difficult to comprehend how his fellow priests could have missed what was happening. "They had to know," says Fontaine. "They always saw me in the middle of the night making sandwiches, making noise in the kitchen. Sometimes we would watch TV and I'd be in bikini drawers or something like that." According to Fontaine, Father Cinel's acts of sacrilege weren't confined to his bedroom; one time he told Fontaine he needed an altar boy, persuaded him to serve at Mass, and then had sex with him afterward in the sacristy (a claim Cinel denies). Other sexual rendezvous were held at a country house Cinel bought in Mississippi and at the borrowed homes of various parishioners. Wherever he was, Cinel recorded his trysts on video. "He had this obsession with the camera," Fontaine reports. "Everywhere he went, the camera was with him. He was always taking pictures of everything."

While Cinel was extremely skillful at fostering Fontaine's sense of emotional dependency, he apparently didn't hesitate to use harsher forms of leverage as well. Early in his relationship with Fontaine, whose troubled adolescence included at least one episode as a juvenile offender, Cinel went to court with the boy to help get him out of some minor skirmish with the law. The judge released Fontaine on probation, under the priest's supervision. "Father is willing to work with you and willing to help you," said the judge. "I hope that will be sufficient to get you on the right track, young man." According to Fontaine, whenever he resisted Cinel thereafter, Cinel would threaten to have him sent to prison. "Dino Cinel may have told him that he may report him to the judge if he didn't do certain things," says Buddy Lemann, Cinel's lawyer. "But it's our position that Chris Fontaine voluntarily entered into all acts with Dino Cinel."

These days Fontaine works as a carpenter when he can, but his lawyers and his psychologist say he's in tenuous shape at best. "Chris is a mess," attests David Paddison. "He's probably going to need some type of medical care forever."

Ronnie Tichenor was in residence at a home for runaway children in the French Quarter when he first met Father Cinel. "He told me he was looking out for my welfare, that he could help me better achieve an education and a better position in life," Tichenor says. Cinel also told him many of the same lines he had used with Fontaine, such as the one about being a "father in need of a son." Although Tichenor is now a tall, strapping darkhaired young man, in one videotape Cinel can be heard bragging about how small the boy was when they first had sex. Like Fontaine, Tichenor became a familiar face at the rectory. At one point he got very upset about his relationship with Father Cinel and even confided in another priest, but his protests were brushed off. "I did break down emotionally with Father Michael," Tichenor told Angelico. "But he did not act like there was anything strange or forbidden. He comforted me for five minutes in a general sense, and that was it." In a later deposition Father Michael Fraser said he had attributed Tichenor's angst to "just basic adolescence" and never even realized the boy was upset about Father Cinel. However, the attitude of Cinel's colleagues had a profound impact on the teenager. "I knew that all the other priests and the other associates at the church were familiar with the goings-on; they couldn't help but have been aware," Tichenor said. "And if they accepted it, I felt it must be right, even if it seemed wrong to me.... Because of the general acceptance of everyone around me, I assumed it was me who was confused."

Tichenor has put some distance between himself and Cinel since then, moving to Florida and going to work for a mosquito-control service. But he suspects he knows what Cinel is up to these days. "He looked for guys in basically the same position as myself, who were in need of leadership and support from a male figure, boys who had no father figure at home," Tichenor says. "He has this sense that these things are O.K. He is able to instill this sense of security in young boys. I hate to think of the possibilities."

For Tichenor himself, some of the possibilities are terrifying; both he and Fontaine wonder if Cinel infected them with the AIDS virus, but they are too scared to be tested. Nor is Ronnie the only Tichenor with cause for concern: Cinel also managed to ensnare his twin brother. Cinel, who enjoyed threesomes, often encouraged Ronnie and Chris to have sex as well. With both boys the priest sometimes discussed his porno-house connection in Denmark and speculated on the possibility of selling pictures or videos abroad, but neither boy was aware that any material had changed hands until Fontaine saw his own photographs in Dreamboy U.S.A. Although Cinel says he never got any money for them, their existence raised new questions. Cinel was earning $42,000 a year at Tulane, and although he was receiving free room and board at St. Rita's, his expenses were considerable. In addition to the country house in Mississippi, he also bought a duplex and a ten-unit apartment building in New Orleans, a speedboat, and a Lincoln Town Car. After he left the rectory, he bought a $200,000 house a few blocks from Tulane. How did he finance it all? His lawyer, Buddy Lemann, smiles enigmatically. "Manna from heaven," Lemann drawls, mouthing his frayed cigar.

Lemann, who is best known in New Orleans for defending members of the Marcello crime family, portrays both of the civil lawsuits currently pending against Cinel as cynical attempts by "two streetwise consenting adults" to fatten their bank accounts. "Chris Fontaine is pissed off because he thinks Dino sold his pictures and made a lot of money," Lemann charges. "Chris is a hustler who thinks he's been out-hustled. I think this is a case of two homosexuals having a fight."

In fact, Fontaine, who says his sexual preferences were always heterosexual, has since married and fathered two children, gotten divorced, and is now planning to marry again. Tichenor has also married, although at one point, he says, Cinel lobbied hard against his emerging heterosexual orientation. "I was approximately fifteen years old when I found out what homosexual sex was, and that that was what I was involved in," says Tichenor. When he told Cinel he liked women, "he tried to sway me. He told me that men knew men better and men were to be together." According to Lemann, Cinel denies having tried to steer Tichenor toward homosexuality.

Since his public exposure, Cinel has often accused his critics of homophobia, and Lemann enjoys casting, this case as a noble crusade against bigotry. "I'm going to elicit the gay and homosexual community to get behind this," he vows. "This is positively a gay-rights issue. This guy is being crucified because he had a homosexual tendency. If it was little girls, you wouldn't have had nearly the same amount of commotion.... Greed and sex, that's what this case is about. Cinel's motivation was sexual; his partners' motivation was greed. I think Dino Cinel may be a sinner, but he's not a criminal."

Those closest to Cinel seem to accept his assertion that he has put his pedophiliac proclivities behind him. "It was a pathology in his past," his wife told Lemann. Whatever Pollock chooses to believe, however, even a passing familiarity with the literature on pedophilia would indicate that this is highly unlikely. "We certainly would never talk about this as being curable," says Dr. Fred Berlin, the director of the Sexual Disorders Clinic at Johns Hopkins. "If you're sexually attracted to children, that doesn't change; that's with you for the rest of your life. We do believe that pedophiles can, with proper treatment, learn to control themselves so they don't continue to pose a danger."

Although anyone who molests a child under the age of consent is legally a pedophile, technically Cinel is probably an ephebophile, or one who is attracted to adolescents; the term "pedophile" is used clinically to describe those who are sexually drawn to pre-pubertal children. Cinel's commercial pornography collection favored pre-pubertal boys, but his known real-life encounters were generally with teenagers. Most pedophiles are believed to be heterosexual in their orientation, but experts are finding a different pattern within the priesthood. "The overwhelming majority of priests we've seen would have the diagnosis of homosexual ephebophilia," says Dr. Berlin.

Whatever the age of their victims, pedophiles are notoriously difficult to treat. "Traditionally, using psychoanalytic techniques or behavioral therapy has not been that successful," says Dr. Eli Coleman, director of the Program in Human Sexuality at the University of Minnesota Medical School. Some programs report a significant degree of success with a combination of group therapy, behavior modification, and medication, hormonal and otherwise, but most experts agree that progress is difficult and the subject's full cooperation is crucial.

A higher rate of success is found with pedophiles who are distressed about their urges and wish they were not attracted to children. The task is much harder with those untroubled by a guilty conscience. "Not only are they sexually attracted to children, but there's no conflict between that fact and the sense of right or wrong, says Dr. Berlin. "Trying to treat somebody like that is like trying to treat an alcoholic who denies he has a drinking problem." The prognosis is even bleaker when offenders are simply incarcerated without treatment. "There's an 80 percent recidivism rate if you just put pedophiles in jail and let them out," says Dr. Jay Feierman, a psychiatrist who has treated an estimated three hundred priests for pedophilia at Servants of the Paraclete Treatment Center, a New Mexico facility run by a Catholic religious order.

Cinel claims to have gone for counseling in New Orleans "for a couple of years every week," and says he stopped all sexual activity with teenage boys in 1986. However, he has frequently seemed to lack any sense of remorse, and in his 1990 deposition he even boasted that he had helped Chris Fontaine. "Were you trying to help him get his life together by having sex with him?" he was asked.

"Probably, considering the promiscuity in which he was living, I was the best person he could have sex with," Cinel said smoothly. "Knowing the other characters he was involved with, yes."

To the contrary, many experts say. "Because of the position of trust and authority that a priest holds in a child's life, when sexual abuse takes place the greatest damage done to the child is the betrayal of that trust," attests Dr. Mulry Tetlow, a clinical psychologist and former Jesuit priest. "The damage is much more severe than sexual abuse by a stranger or babysitter."

Nevertheless, those who have had recent conversations with Cinel report a disturbing sense that he is more aggrieved than penitent. "He just doesn't understand," says Sandi Cooper, a fellow history professor at the College of Staten Island, adding that Cinel was "shocked" that the school wants to get rid of him. "He's upset; he feels betrayed." Robert Viscusi, a Brooklyn College professor who also talked to Cinel over the summer, says, "There is this strange kind of dissociation that I found more troubling than anything else. He talks about it very dispassionately and loftily, as if it all had to do with somebody else." Lawrence Powell, a Tulane history professor and former friend of Cinel's, observes, "Even today, he has no moral sense. I don't think he feels he's done anything wrong."

Cinel certainly doesn't deny his transgressions; indeed, before Buddy

Lemann signed on as his lawyer and told him to shut up, Cinel was even

discoursing to the tabloids about the fine points of his sexual tastes.

"He explained to reporters at a press conference in his home that

sex with young men gave him a greater sexual high, while sex with his

wife was 'more emotionally fulfilling,'" the Staten Island Advance

reported. With intimates, he can be even more forthcoming. W. D. Atkins

was Cinel's lawyer until earlier this year, when they parted company over

the $30,000 he says Cinel still owes him (a debt Cinel denies). But the

attorney remains sympathetic to Cinel's case, and it was to Atkins that

Cinel offered one of his more explicit confidences—one that would

not seem to augur well for the former priest's prospects of leading a

reformed life. "He told me, 'I just love to fuck young boys in the

ass,'" Atkins says. "He's delighted with his attitude. He's

not embarrassed in the least."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.