Files show Law, others backed priest

By Walter V. Robinson and Thomas Farragher

Boston Globe

April 9, 2002

http://www.boston.com/globe/spotlight/abuse/stories/040902_shanley_record.htm

For more than a decade, Cardinal Bernard F. Law and his deputies ignored

allegations of sexual misconduct against Rev. Paul R. Shanley and reacted

casually to complaints that Shanley endorsed sexual relations between

men and boys, according to an avalanche of documents that were made public

yesterday.

|

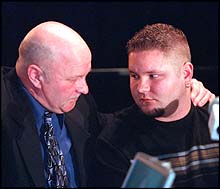

| Rodney Ford, left, with his son Gregory, who was allegedly molested by the Rev. Paul R. Shanley. (Globe Staff Photo / Jonathan Wiggs) |

As recently as 1997 - after the Boston archdiocese had paid monetary settlements

to several of Shanley's victims - Law did not object to Shanley's application

to be director of a church-run New York City guest house frequented by

student travelers.

Like a priest clad in a Teflon cassock, Shanley received an extraordinary tribute from Law when he retired in 1996, not two decades after Shanley asserted in public remarks that there was no psychic harm from engaging in taboo practices like incest or bestiality.

In the Feb. 29, 1996, letter, the cardinal declared, ''Without doubt over all of these years of generous and zealous care, the lives and hearts of many people have been touched by your sharing of the Lord's Spirit. You are truly appreciated for all that you have done.''

Yesterday, law enforcement officials were more skeptical. Kurt N. Schwartz, chief of the criminal division under Attorney General Thomas F. Reilly, and three State Police detectives attended the 21/2-hour news conference at which the documents were unveiled by attorney Roderick MacLeish Jr. He obtained them under a court order on behalf of Gregory Ford, a Newton man who allegedly was molested by Shanley between 1983 and 1989.

''We're taking a serious look at today's developments,'' said Ann Donlan, a spokeswoman for Reilly. She declined to elaborate, but said the presence of a senior member of Reilly's staff ''speaks for itself.''

Arthur Austin, another alleged victim of Shanley who attended the news conference, expressed bitterness and dismay at the church's longtime protection of Shanley, who is now 71. ''If the Catholic Church in America does not fit the definition of organized crime, then Americans seriously need to examine their concept of justice,'' Austin said.

The 800 pages of documents, in some major respects, are not unlike the church records, also forced into the open by court order, about former priest John J. Geoghan. In each case there was a priest known to have molested children, two cardinals and several bishops seemingly uninterested in complaints about him, and prelates who transferred him without alerting his new superiors that he was a danger to children.

In both cases, church lawyers waged legal battles to protect the documents from public release.

Geoghan is now serving a nine-to-10 year prison sentence. Shanley, because he left Massachusetts for California in 1990, is believed to be potentially vulnerable to criminal charges because the clock on the statute of limitations stopped running when he left the state.

Yesterday's documents on the sexual misbehavior of a second priest is likely to increase public suspicion that the archdiocese holds embarrassing files on others among the nearly 100 diocesan priests whose names have been turned over to prosecutors since January.

Donna M. Morrissey, the cardinal's spokeswoman, issued a statement last night declaring that the archdiocese ''has learned from the painful experience of the inadequate policies and procedures of the past.''

Her statement, which made no mention of the Shanley documents, said: ''Whatever may have occurred in the past, there were no deliberate decisions to put children at risk.''

But MacLeish, who said there are 26 known Shanley victims, called the documents astonishing for what they say about the depth of the archdiocese's knowledge of Shanley's sexual habits and for the disdain they show for his victims, many of them allegedly abused during the 1970s, when Shanley was a controversial ''street priest'' in Boston.

''This man was a monster in the Archdiocese of Boston for many, many years,'' MacLeish said. ''He had beliefs that no rational human being could defend.''

MacLeish, wearing a wireless microphone and narrating a computer-generated tour of some of the 818 documents handed over by the archdiocese, said warning signs about Shanley date back as early as 1967.

''All of the suffering that has taken place at the hands of Paul Shanley - a serial child molester for four decades, three of them in Boston - none of it had to happen,'' he said.

Before an audience of journalists, accusers' families, and parishioners from the Newton church Shanley served as curate and pastor from 1979 to 1990, MacLeish argued that Law, his predecessor, Cardinal Humberto S. Medeiros, and their top aides were complicit in covering up the church's knowledge of a molester in their midst. Letter after letter was projected onto a large screen in a Boston hotel conference room, with warnings from people who recoiled at Shanley's casual attitude about sex between men and boys, or who reported that he had masturbated one boy and identified other possible victims with names, telephone numbers, and addresses.

In rebutting a 1967 complaint that he had molested three boys, a letter from Shanley to Monsignor Francis J. Sexton denied that he had touched any of the boys. ''... It is indeed a comforting prospect to realize that any allegations which might in the future be made against me involving women will be given far less credence than ordinary in the light of my presumed predilection for pederasty,'' Shanley wrote.

But when Shanley was finally sent for treatment in late 1993 to the Institute of Living in Hartford, after some of his victims pressed claims against the archdiocese, he admitted that he had molested boys and had also had sexual relationships with men and women.

The handwritten notes of Rev. William F. Murphy, an archdiocesan official, note that Shanley's treatment concluded that he had a personality disorder, was ''narcissistic'' and ''histrionic'' and ''admitted to substantial complaints.'' The record cited his admissions to nine sexual encounters, four involving boys.

Whether or not church officials believed Shanley's denials in the 1960s and 1970s, there was little doubt about his controversial stance on sexual practices.

In 1977, for instance, the archdiocese was alerted by an appalled Catholic that during a public address in Rochester, N.Y., Shanley asserted that the only harm that befalls children from having sexual relations with adults is from the trauma of societal condemnation of such acts.

''He stated that he can think of no sexual act that causes psychic damage - `not even incest or bestiality,''' according to a letter sent to Medeiros, who died in 1983.

Indeed, the records in Shanley's personnel files disclose that Medeiros wrote to the Vatican in February 1979 about Shanley's comments about sexual practices. In the letter, Medeiros called Shanley a ''troubled priest.''

Two months later, Medeiros was alerted by a New York City lawyer that Shanley had been quoted as making similar remarks in an interview about man-boy love with a publication called Gaysweek.

Within days, according to the church records, Medeiros removed Shanley from his street ministry, sending him to St. John the Evangelist Church in Newton, but with an admonition.

''It is understood that your ministry at Saint John Parish and elsewhere in this Archdiocese of Boston will be exercised in full conformity with the clear teachings of the Church as expressed in papal documents and other pronouncements of the Holy See, especially those regarding sexual ethics,'' Medeiros wrote in a letter to Shanley.

Six years later, Law promoted Shanley to pastor. And four months after Shanley became pastor in 1985, the archdiocese reacted nonchalantly when a woman alerted the Chancery that Shanley gave another talk in Rochester in which he once again endorsed sexual relations between men and boys.

In response, Rev. John B. McCormack - now the bishop of Manchester, N.H. - sent a friendly note to Shanley, a seminary classmate. In a letter signed, ''Fraternally in Christ,'' McCormack wrote: ''Would you care to comment on the remarks she made. You can either put them in writing or we could get together some day about it.''

There was no evidence in the files that Shanley responded in writing. Through a spokesman, McCormack yesterday refused to comment on the documents.

Three years later, in 1988, a man complained to the archdiocese that Shanley began a sexually explicit conversation with him. But despite the evidence in the Chancery's files about earlier accusations made against Shanley, Bishop Robert J. Banks, Law's top deputy, concluded in a memo that nothing could be done because Shanley denied that the incident occurred.

It was Banks, the Globe reported yesterday, who cleared the way in 1990 for Shanley to take an assignment in a California diocese with a letter asserting that Shanley had had no problems during his years in Boston.

Banks, who is now bishop of Green Bay, Wis., said in a brief statement from his spokesman: ''Obviously, I was not aware of any allegations against Father Shanley before I sent the letter.''

Yesterday, Austin, who says Shanley abused him from 1968 to 1974, evoked an audible gasp when he retold a conversation he said he had with Murphy, the archdiocesan official. Austin said the conversation drove him from the Roman Catholic Church and prompted his decision to get legal help.

''He called me about three months after I had come forward in November of 1998 and said to me: `Arthur, I'm going to have to be very careful about meeting with you.' I said, `Why is that, Bill?' And he said to me, `Because I've spoken to experts here at the Chancery who have told me that you are going to want from me what you wanted from Father Shanley.' ''

Murphy did not return telephone calls seeking comment.

MacLeish said Murphy's response to Austin illustrates a cavalier attitude the church used toward victims. Sometimes, he said, citing one document that appears to refer to a woman who accused Shanley of being a child molester, they put telephone complainers on hold, hoping they'd go away.

In December 1989, Shanley stepped down as pastor in Newton for reasons that are not clear from the documents. He was placed on sick leave and moved to California as a part-time priest at a parish in San Bernardino. During the three years he was there, the Globe reported yesterday, Shanley and another priest from the Boston Archdiocese, Rev. John J. White, were co-owners and operators of a Palm Springs motel that catered to gay clients.

It was during that period that McCormack, who visited with both men, corresponded warmly with Shanley over Shanley's regular complaints that the archdiocese was not giving him enough financial support. He accompanied one plea to McCormack with what appeared to be a warning that reporters were calling him and there might be a ''media whirlwind.''

In December 1990, Law himself wrote to Shanley, granting his request to extend his sick leave for a year. Extending his ''warm personal regards,'' Law said he was saddened to hear about Shanley's ''malaise.''

McCormack and Shanley also corresponded about a proposal, apparently by Shanley, to create a ''safehouse'' in Palm Springs where the Boston Archdiocese could send ''warehoused'' priests. When he heard no response, he wrote McCormack, ''I assume the hesitation is about me, not the concept.''

Shanley, however, moved to New York City in 1995, and took a job at Leo House, a guest house run by an order of nuns on West 23d street in Manhattan. Its guests included teenagers. A letter in the files by an unidentified archdiocesan official says that the job ''was a placement of his own finding'' and expresses concern that ''it would be hard to defend if any public disclosure was made about it; i.e., NYC, possible questionable supervision, transient guests, young people, not of our making, etc.''

Despite those concerns, Shanley remained at Leo House for nearly two more years, eventually as acting executive director. And had New York Cardinal John O'Connor not vetoed the proposal, Law was prepared to approve him becoming permanent director in 1997.

During Shanley's long-running effort to get that job, he wrote a letter of frustration to Rev. Brian M. Flatley, an aide to Law, saying he had ''abided by my promise'' not to tell anyone that he himself had been molested as a teenager, and when he was a seminarian, by a priest, a faculty member, a pastor, and an unidentified cardinal.

In June 1997, Law wrote a letter to O'Connor, citing ''some controversy'' in Shanley's past, but adding: ''If you decide to allow Father Shanley to accept this position, I would not object.'' But Flatley never sent the letter, after learning that O'Connor ruled out the promotion.

Not long after that, Shanley moved to San Diego.

Globe Staff reporters Kevin Cullen, Sacha Pfeiffer, Matt Carroll, and Tatsha Robertson contributed to this report. Walter Robinson can be reached at wrobinson @ globe.com. Tom Farragher can be reached at farragher@globe.com.

This story ran on page A1 of the Boston Globe on 4/9/2002.

The materials on BishopAccountability.org are offered solely for educational

purposes. Should any reader wish to quote or reproduce for sale any documents

to which other persons or institutions hold the rights, the original publisher

should be contacted and permission requested. If any original publisher

objects to our maintaining a cache of their documents for safekeeping,

we will gladly take down our cache of those documents and offer links

to the original publisher's posted versions instead.

Original material copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.