MANHATTAN BEACH (CA)

New York Times [New York NY]

March 31, 2021

By Alan Yuhas

Vigilante parents dug under a preschool, searching for secret tunnels. The police swapped tips on identifying pagan symbols. A company that sells toothpaste and soap had to deny, repeatedly, that it was acting as an agent of Satan.

Early in the 1980s, baseless conspiracy theories about cults committing mass child abuse spread around the country. Talk shows and news programs fanned fears, and the authorities investigated hundreds of allegations. Even as cases slowly collapsed and skepticism prevailed, defendants went to prison, families were traumatized and millions of dollars were spent on prosecutions.

The phenomenon was so sprawling that, in its aftermath, it took on several names, like the ritual abuse scare or the day care panic. But one name has increasingly stuck: the satanic panic.

“The evidence wasn’t there, but the allegations of satanic ritual abuse never really went away,” said Ken Lanning, a former F.B.I. agent who worked on hundreds of abuse cases with the bureau’s behavioral science unit. “When people get emotionally involved in an issue, common sense and reason go out the window. People believe what they want and need to believe.”

1980: The ‘proper fuel’ for panic

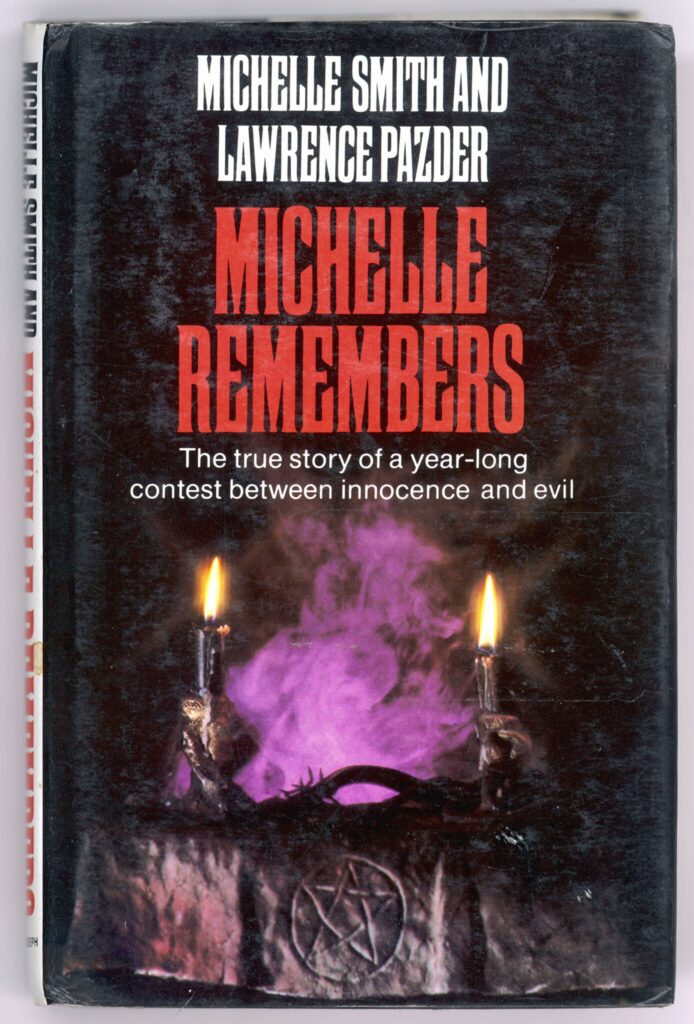

When the book “Michelle Remembers” was published in 1980, introducing readers to a cast of murderous Canadian satanists, it landed on a powder keg of American anxieties, said Mary deYoung, a professor emeritus of sociology at Grand Valley State University.

More women were going to work, by choice and necessity in the wake of the women’s rights movement and as the country struggled with a recession. Conservatism and the religious right were ascendant, and both emphasized the nuclear family. Good day care was hard to find, Ms. deYoung said, and many parents felt guilt for relying on it.

And after decades of denial, the public was starting to confront the problem of sexual abuse, especially involving children. “You hook all of those things together magically and boom — you’ve got the proper fuel for a moral panic,” she said.

The spark, she said, was “Michelle Remembers,” a book by a Canadian psychologist and his former patient about her memories of child abuse at the hands of satanists. Although its lurid claims were quickly challenged, the book was a best seller. Suddenly, it seemed, terror could be lurking in any neighborhood.

The book gave people a villain to look for outside the family, said Sarah Marshall, a host of the history podcast “You’re Wrong About.” What readers heard, she said, was, “Don’t look in the mirror, the call is not coming from inside the house — the satanists are the problem.”

Some social workers and police officers, searching for an authority to help them face the problem of abuse, even adopted it as a training text, she said.

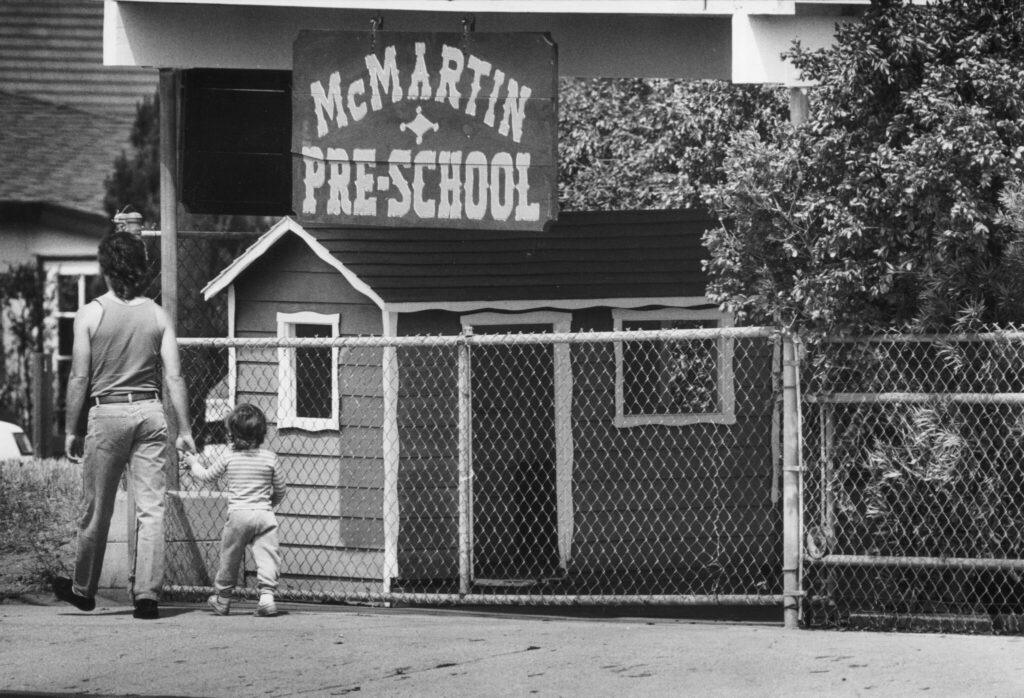

1983: Fear spreads in Manhattan Beach

In the summer of 1983, a woman in Manhattan Beach, Calif., accused an employee at her son’s preschool, McMartin, of abusing him. The police sent a letter to about 200 families, asking for help with their investigation.

“The following procedure is obviously an unpleasant one, but to protect the rights of your children as well as the rights of the accused, this inquiry is necessary,” the police chief wrote, describing alleged sex crimes. “Please question your child to see if he or she has been a witness to any crime or if she has been a victim.”

The letter was “a model of what not to do,” said John Myers, a professor at the University of California, Hastings, and a lawyer who represents child victims of abuse.

The authorities also asked therapists to help interview hundreds of children. They questioned them for hours at a time, often asking leading and suggestive questions, he said. “We as professionals were singularly ill-equipped,” Mr. Myers said. “Nobody had thought about proper forensic interviews in these situations.”

The allegations “didn’t move to full-blown satanism immediately,” said Richard Beck, the author of a book about the panic. “The intermediary steps were people saying there was something weird or elaborate about what happened, and a fair number of those claims came out of the interviews.”

In 1986, prosecutors charged seven employees with more than 100 counts of child molestation and conspiracy. A week later, they dropped the charges against five defendants, citing weak evidence. All the defendants maintained their innocence.

By then, the case was a national spectacle, and prosecutors pursued it despite growing doubts about the original accuser’s story and a variety of fantastical claims from interviews, including a “goatman,” bloody animal sacrifices, a school employee who could fly and acts of violence that left no physical trace. But the trial would not end for years, with no convictions, and prosecutors around the country started dozens of cases like it.

Each authority — the police, prosecutors, psychologists, the media — put pressure on the others to act, said Anna Merlan, the author of a book on the history of conspiracy theories. “It was a very fervid environment,” she said. “Very credible-seeming people were saying: ‘Occult ritual abuse is all around you. We’ve seen it and the signs are visible if you know how to look for it.’”

Seminars on symbols

The authorities tried to make sense of the allegations. Mr. Lanning, the retired F.B.I. agent, said that as “a deluge” of calls about strange abuse began in 1983, he tried to investigate with an open mind. “My attitude was, yes, most anything is possible,” he said. “But where’s the evidence?”

So F.B.I. agents, police officers, lawyers and social workers gathered what they could, and shared their findings at conferences and seminars. They handed out satanic calendars, traded pamphlets about symbols like the “cross of Nero” and the “horned hand,” and copied lists of supposed occult organizations, which included a collective of feminist astrologers in Minnesota.

“A lot of this stuff was being disseminated by law enforcement without efforts to corroborate it,” Mr. Lanning said. “One cop would come up and say, ‘What a load of crap,’ but then another would say, ‘I’ve got to learn more!’”

When Mr. Lanning asked officers how they corroborated information, their stories fell apart, he said. “Oh, I got it from so-and-so,” he recalled hearing. But often, he said, the pamphlets still made it into copy machines and onto the news.

The drumbeat on TV

In May 1985, the news program “20/20” ran a segment on Satan worship that described animal mutilations “clearly used in some kind of bizarre ritual,” rock music “associated with devil worship,” “satanic graffiti” and backward messages in pop songs.

There were a few caveats. The host, Hugh Downs, opened by saying: “Police have been skeptical when investigating these acts, just as we are in reporting them. But there is no question that something is going on out there, and that’s sufficient reason for ‘20/20’ to look into it.”

The program presented cult activity, if not the occult itself, in all but certain terms. “Today we have found Satan is alive and thriving, or at least plenty of people believe he is,” said the correspondent Tom Jarriel. “His followers are extremely secretive but found in all walks of life.” Only near the end of the report did he say that, until evidence was proved, “the link between crime and satanic cults will remain speculative.”

Three years later, NBC commissioned its own special, hosted by Geraldo Rivera, who described gruesome crimes, aired child testimony of abuse and interviewed Ozzy Osbourne. Almost 20 million homes tuned in.

Taking rumors to court

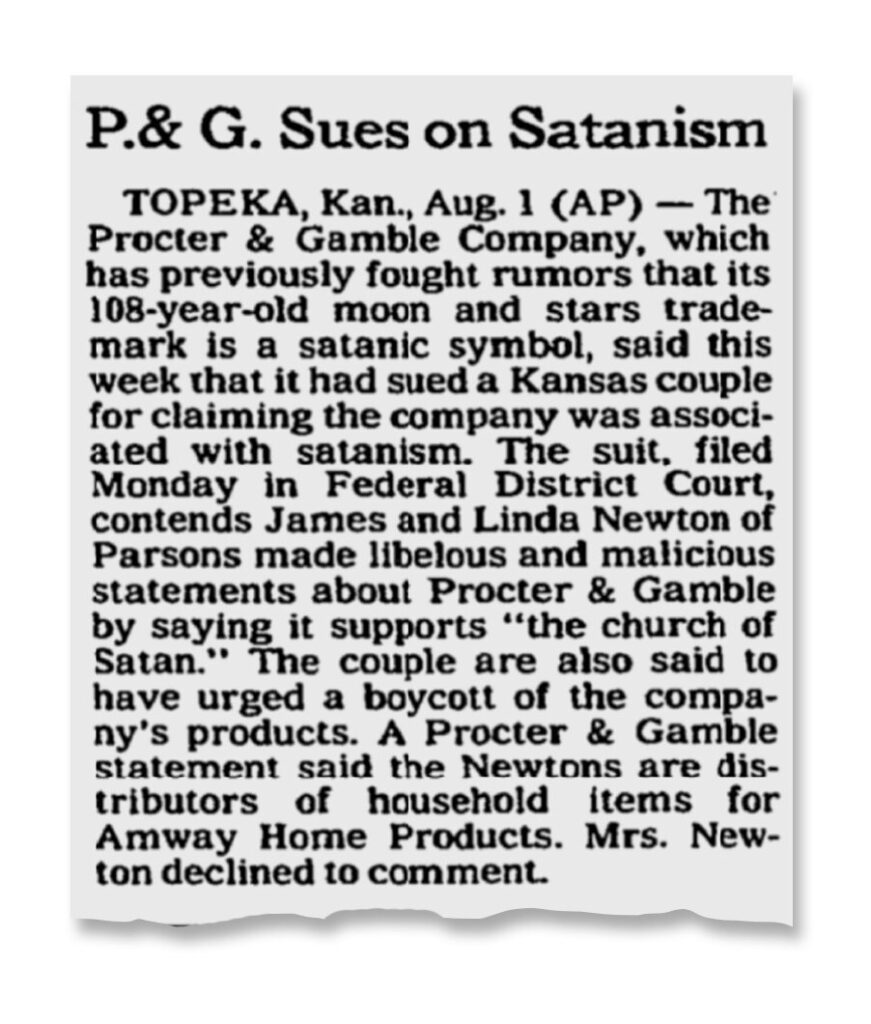

In April 1985, thousands of curious, angry and confused customers were calling the corporate giant Procter & Gamble about leaflets that accused it of using its profits from household goods to support devil worship.

“They simply are not true,” W. Wallace Abbott, a senior vice president said at a news conference. “We haven’t the vaguest idea how it started; all we know is people are believing it. Do you know how hard it is to fight a rumor?”

False rumors had started years earlier, many claiming that its logo, of a bearded man in the moon facing 13 stars, was actually a symbol of the devil. (The logo dated to 1882 and the stars referred to the 13 original colonies.) The company began a two-decade campaign to defend its name, sending representatives to churches, filing lawsuits and pursuing court cases as recently as 2007. It also changed its logo.

Verdicts

In 1990, a jury acquitted the McMartin Preschool defendants on some charges and deadlocked on others, saying it was impossible to determine the truth from the children’s testimony. A second prosecution ended in a mistrial. Prosecutors, having spent $15 million, dropped the case.

Nearly 200 people were charged with crimes over the course of the satanic panic, and dozens were convicted. Many defendants were eventually freed, sometimes after years. Three Arkansas teenagers who became known as the West Memphis Three were freed in 2011, almost 20 years after they were convicted of murders that prosecutors portrayed as a satanic sacrifice. In 2013, a Texas couple were released after 21 years in prison; they were later awarded $3.4 million from a state fund for wrongful convictions.

In 1992, Mr. Lanning, the F.B.I. agent, released an investigative guide that explained his skepticism of satanic abuse claims. Two years later, researchers with the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect found that investigators could not substantiate any of roughly 12,000 accusations of group cult sexual abuse based on satanic ritual.

In a few instances, apologies followed, including from Mr. Rivera and Kyle Zirpolo, one of the former McMartin students who made allegations to the police. “I lied,” he told The Los Angeles Times. “It was an ordeal. I remember thinking to myself, ‘I’m not going to get out of here unless I tell them what they want to hear.’”

.