WOODLAND (NJ)

nj.com [New Jersey]

May 1, 2021

By Susan K. Livio, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com

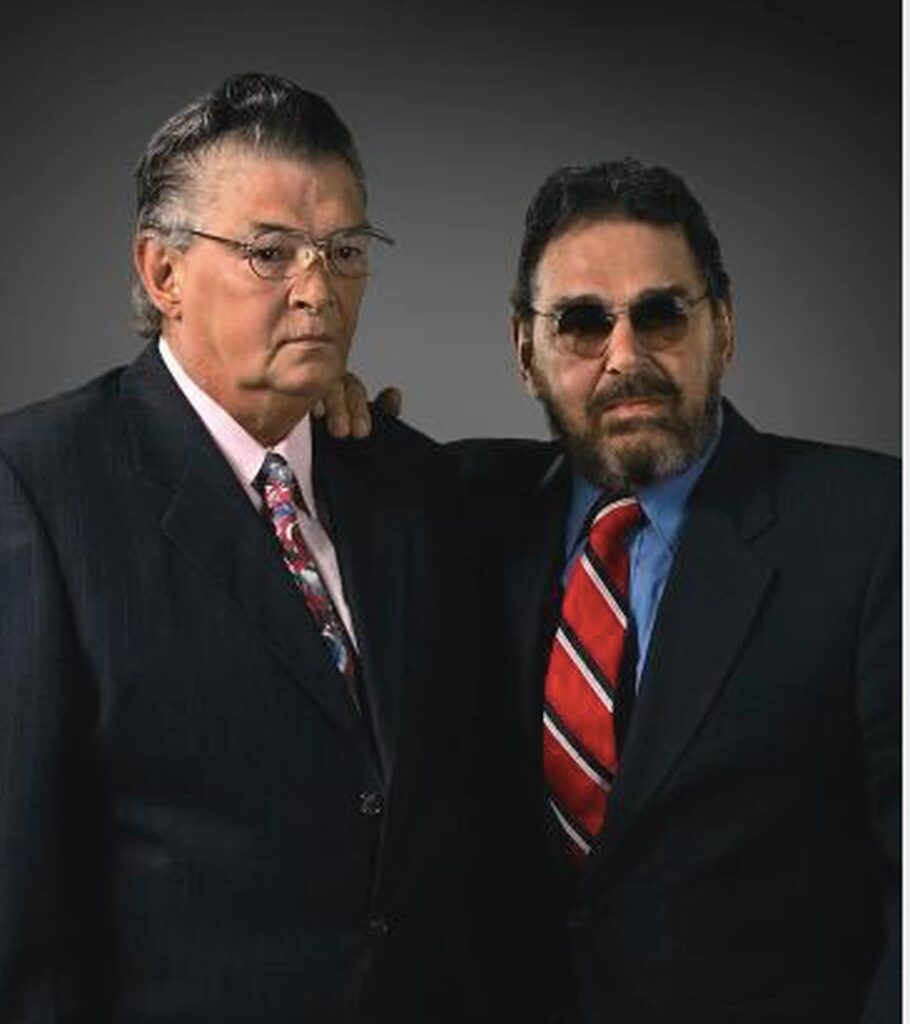

[Photo above: From left to right, 7-year-old “Chuckie” and 8-year-old Bobby Carroll in 1948, two orphans in foster care, before they were sent to the New Jersey State Colony for Boys, an institution later renamed the New Lisbon Developmental Center.]

Charles Carroll was 8 and his brother Robert was 9 when they were delivered to a state institution for children with developmental disabilities in rural Burlington County more than 70 years ago.

Neither boy was disabled. But their parents had abandoned them, and foster families had returned them.

The New Jersey State Colony for Boys, today known as the New Lisbon Developmental Center, became their home and their hell. They were raped by older boys and employees and deprived of an education and any hope of escaping before they reached adulthood, according to Charles A. Carroll’s 2005 harrowing memoir, Hard Candy.

Yet when Bobby died from COVID-19 last year, Chuck Carroll chose to scatter his beloved brother’s ashes in a cemetery on the grounds of that facility in New Lisbon.

Friends who joined Carroll one cloudy Saturday morning in April to witness Bobby’s interment admitted they were confused as to why Chuck had chosen New Lisbon for his brother’s final resting place.

“This was our only home — good or bad,” said Carroll, 78, who lives in Ocean County some 20 miles away.

“This is what I want for myself too,” Carroll said, gesturing toward his friends, “and they are going to take care of that.”

Returning to New Lisbon brings back the memories, but they do not overwhelm him anymore, he said.

“All of the pain I carried throughout my life — having written my book took care of that,” he said. “It was a rebirth, and it just removed all of that hate and bitterness. I am at peace with myself today.”

Carroll’s state of mind improved that week when The Herman Law Firm in New York filed a $10 million lawsuit on his behalf. It accuses the state of gross negligence for hiring the four employees who sexually assaulted him, and for refusing to investigate and protect him when he told managers at the time he and his brother had been abused, according to the complaint filed in state Superior Court in Mercer County.

The sexual assaults continued even when Carroll turned 13 and he and two of his abusers were transferred to Edward R. Johnstone Training and Research Center in Bordentown, another state facility for juveniles with mental and behavioral disorders, according to the lawsuit.

Carroll said he found an attorney and explored his options after Gov. Phil Murphy signed a law two years ago expanding the statue of limitations on lawsuits filed by victims of sexual assault,

A spokesman for the state Attorney General’s Office, which would represent the state against Carroll’s claim, declined to comment.

“I am not looking for an apology from these people,” Carroll said. “I just want them to understand that because of their negligence, there was a lot of damage done to others and myself.”

Especially Bobby.

Carroll said he never learned why his mother surrendered her sons to St. Walburga, a Catholic orphanage in Roselle in 1943, a year after he was born. They never knew their father. Three years later, they entered foster care and were quickly deemed hard to place. One family lost interest after the woman unexpectedly became pregnant, Carroll said.

Like many of the boys they would meet at New Lisbon, they were not intellectually disabled. (A 1991 letter published in the book from a psychologist who was an intern in the 1950s and had befriended Carroll said: “… Your thinking and problem-solving seemed perfectly normal.” )

The book describes New Lisbon as a violent and chaotic place, ruled by a number of sadistic or indifferent staff and aided by teenage enforcers — residents themselves — who had becomehardened by their own abuse. The book’s title, Hard Candy, comes from the treats a verbally abusive “cottage mother” handed out to boys who behaved. But an older boy named Jackson swiped most of the candy for himself and doled it out to kids like Chuck Carroll to keep them quiet after being raped by him, the book says.

The Carroll brothers ran away. They talked back. Their antics and insubordination landed them at Cedar Cottage, the closest thing to jail on the New Lisbon grounds, according to the book.

“Cedar’s residents were the embodiment of the Colony’s ultimate failures. Most had been renegades to stand up to New Lisbon’s wrongs — pleading for basic decency, more rights, and a democratic way of life — but they did so with fewer and simpler words. Residents who spoke the loudest and became a nuisance to those in charge were either sent to Fern Cottage or shipped to Trenton where their minds would be ‘fixed’ once and for all.”

“Trenton” referred to what is today Trenton Psychiatric Hospital, which practiced electroshock therapy, then a relatively new and crude treatment. “Many who went to Trenton were never the same after they returned — they would come back just the way New Lisbon wanted them: docile, obedient and unassuming,” Carroll wrote.

New Lisbon ultimately sent Bobby, then 12, to Trenton. Carroll said his brother told him he had endured some 200 treatments, which erased his prankster and brazen tendencies and inflicted enough damage that “he became more acclimated to the environment,” Carroll said. Bobby finally fit in with the other boys who were limited intellectually.

“Prior to shock treatments, he was angry like me,” Carroll said.

Carroll was finally discharged from Johnstone in 1959 when he was 17 and worked as a custodian at a nursing home in Atlantic City for a year. He later moved to California where he started an electrical contracting business. He sold it in the 1990s and started working on his book, a project that would take seven years.

Chuck and Bobby spent more of their adult years apart than together, losing track of each other twice.

After Carroll’s book was published in 2005, he said he hired a private investigator to locate Bobby. The investigator tracked him to Fort Dix, where he was a dishwasher who would soon be out of a job. He was caught sleeping in the boiler room after his shift.

“He was homeless,” Carroll said. “I sent him a Greyhound ticket. I met with him at the Greyhound bus terminal station in Palm Springs and took him to my home in Yucca Valley, California. I promised he would never be homeless again.”

“He was a wonderful man, gentle, loving soul who people took advantage of all his life. And when I got him in 2005, I swore no one would ever hurt him again,” Carroll said.

In 2019, Bobby’s health declined. Diabetic neuropathy made walking painful. He also had trouble swallowing, Carroll said. Taking care of his brother became more than he could handle. He placed Bobby in a nursing home. “And that is where he got the COVID-19,” he said, his eyes filling with tears. He died May 29, 2020 at age 78.

On April 10, Carroll met his friends, as well as a reporter and photographer from NJ Advance Media at the Wawa off Route 72 in Woodland Township. Carroll led the four-car caravan into a side entrance of New Lisbon, which became a coed institution for adults with developmental disabilities in 1977, according to the Department of Human Services.

Joanna Kruse, a teacher who befriended the Carroll brothers after reading the book in 2018, carried two bouquets of long-stemmed flowers to the tiny cemetery tucked into a corner of the property.

Carroll tossed fistfuls of ash along a bare stretch of grass between the rows of weathered tombstones and a statue of an angel. Kruse followed behind him, dropping stems from the bouquets cradled in her arm. He paused and tipped his cap, his face pinched with pain.

When the urn was empty, Carroll leaned on the fence and wept as he described what he was thinking as he said goodbye to his brother.

“I was telling him how much I loved him. At the end there, where I took my hat off, I said, you will forever be in my heart,” he said.

He said he didn’t bother with prayers. “I’m sorry to admit this, but there is no God left in me. After so many tears and praying…I just let it all go.”

Carroll said he does speaking engagements and has testified on behalf of sexual abuse victims before legislative committees at the Statehouse. He turned the book into a screenplay, State Colony, which was a quarterfinalist in the Golden Script competition last year. Through his blog, he keeps tabs on New Lisbon and often hears from families and other “insiders” who sometimes complain about the care.

There is a place for facilities like New Lisbon, Carroll said, “but what they need to do is better train those who are close to the resident. For some of them, it’s just a paycheck.”

Kruse said the book “was so raw and sincere,” she and her boyfriend contacted Carroll through his website, hardcandyblog.com. They call each other close friends.

“I wanted to dive into the book at every moment and put my arms around those two little boys, those orphans, who were on a daily basis being harassed and tortured, living in fear every single day,” Kruse said.

Carroll said he was forced to relive the abuse while he wrote the book, but it exorcised the demons in his mind.

“I didn’t write the book for myself, but I was the first one handsomely paid with the solace and peace,” he said. “Psychologists, psychiatrists, group therapy, all of that stuff didn’t work. The book took care of it.”

Carroll said It’s the memories of Bobby as a child at New Lisbon, the jovial prankster and his defender, that give him comfort now. That’s why bringing his brother’s remains here made sense to him, and why he wants to have his ashes laid to rest here, too, he said.

“I did this because it is how I remember him here,” Carroll said. “I belong here, not because it’s New Lisbon, but because he’s here now, And I want to be with him.”

Our journalism needs your support. Please subscribe today to NJ.com.

—

Susan K. Livio may be reached at slivio@njadvancemedia.com. Follow her on Twitter @SusanKLivio.