CORK (IRELAND)

Irish Examiner [Cork, Ireland]

June 27, 2021

By Jess Casey

Have we ever grasped how to adequately atone for the sins of the Church and of the State in this country for the abuses suffered in industrial schools, day schools, symphysiotomy, and Magdalene laundries? Jess Casey finds out

“Redress; to remedy, or set right.” The history of modern Ireland is woven tightly with a litany of human rights violations, often referred to as ‘historical’ abuses as if they are confined, now, only to books.

These traumas are living, breathing memory.

We live amongst the legacy of abuse of power, most often inflicted on children, women, and unmarried mothers.

Redress should be an acknowledgment of victims’ pain, and for the loss of opportunity, they suffered as a result, as well as a symbol of reconciliation and a move towards righting an injustice of the past.

But have we ever grasped how to adequately atone for the sins of the Church and of the State?

Across two days, the Irish Examiner will look at the redress schemes set up in the aspiration of righting some of these wrongs; abuses suffered in industrial schools, day schools, symphysiotomy, and Magdalene laundries.

With a redress scheme currently in development for survivors of Mother and Baby Homes, now is a good time to examine the mistakes and missteps of past schemes.

Schools

Contemporary schools are far from perfect but, for the most part, they are happy places.

Like much of Irish society, they have also experienced massive changes in a number of short decades.

When you consider that corporal punishment in the classroom was banned officially not even 40 years ago, many parents in their 50s had vastly different experiences of school than those of their children.

Today, student wellbeing is built into the curriculum.

Teachers are mandated to report suspected abuse, as are a whole range of professionals who work with or come into contact with children as part of their duties.

It’s not a faultless system, but a system nonetheless, and a far cry from the deeply flawed school system of the early 20th century.

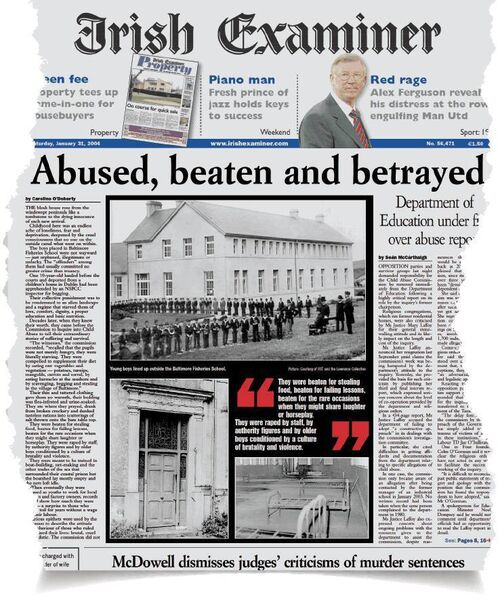

The publication of the Ryan Report put the scale of neglect, and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse inflicted on thousands of students by religious and lay adults responsible for their care in black and white.

Industrial schools

Industrial schools, funded by the public and run by religious orders, were born out of widespread abject poverty to care for neglected, orphaned, and abandoned children potentially exposed to crime, according to the landmark report.

High unemployment, a lack of welfare benefits, and poor housing conditions combined to create extreme and unnatural conditions in which “many related evils flourished”.

“Against this background of extreme poverty, some saw the schools as no worse than anything else and as offering children at least adequate food and housing.” In 1929, changes to the Children’s Act meant that a child could be sent to an industrial school if their parents were unable to support them.

In 1943, the number of children admitted to industrial schools peaked, the year before changes were made to the Children’s Allowance.

The expansion of the allowance in 1944 is generally accepted to have contributed to the subsequent decline in numbers at the schools, the Ryan report notes.

Industrial schools were financed and, in theory, overseen by the Department of Education, while the individual religious orders and congregations were tasked with their day-to-day management.

Inspections

The Department of Education also defined the standards of accommodation, clothing, diet, visits at the schools, as well as the time of students’ discharge, and its inspectors had the duty of ensuring these regulations were met.

“The Department had too little information because the inspections were too few and too limited in scope. If the Department had been in possession of better information about the schools, it would have been in a stronger position to exercise control.”

“The officials were aware that abuse occurred in the schools and they knew the education was inadequate and the industrial training was outdated.” Many of the same religious orders were also involved in the running of national and day schools.

National education was paid for by the Government, but it did not manage it or administer it; again, this responsibility lay elsewhere.

The functions of an individual school fell to a local manager. In the case of Catholic schools, this was usually a priest appointed by a local bishop.

The process for many abuse survivors seeking access to redress as adults has been adversarial, stressful, and acts as yet another obstacle in their fight for justice. Over the course of this special report, we ask why, and whether any good has come of the State’s attempts at amends.