VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

Washington Post

July 12, 2021

By Chico Harlan and Stefano Pitrelli

[Photo above: The St. Pius X youth seminary in Vatican City, circa 2009. (Courtesy of Kamil Jarzembowski)]

The warnings started coming eight years ago, sent to some of the most powerful figures in the Roman Catholic Church, alerting them to a potential sex abuse crime that stood out from other church cases.

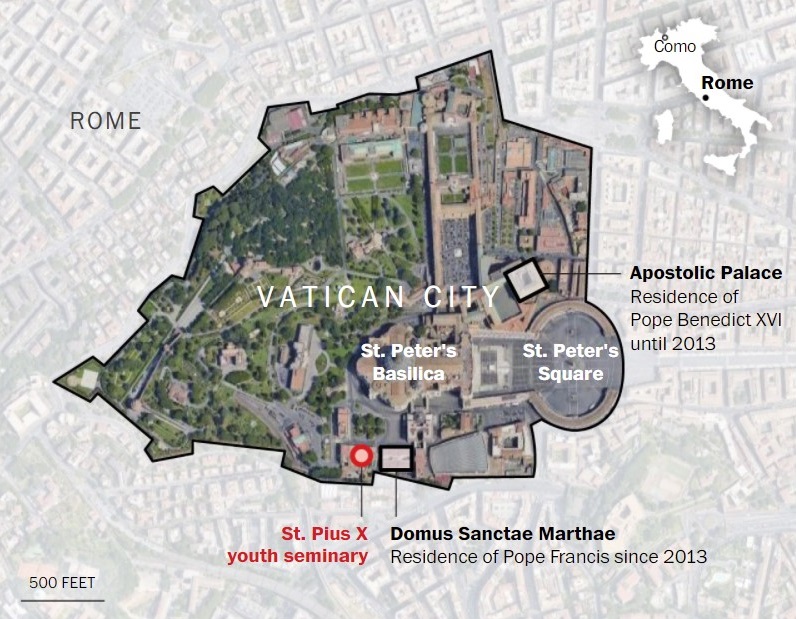

The profile of the alleged abuser, by itself, was unusual: not a priest, but rather a teenage altar boy, who was said to have coerced a peer to engage in various sex acts night after night over six years. And then there was the purported location: inside the Vatican’s own walls, at a youth seminary for the 15 or so altar boys who served the pope.

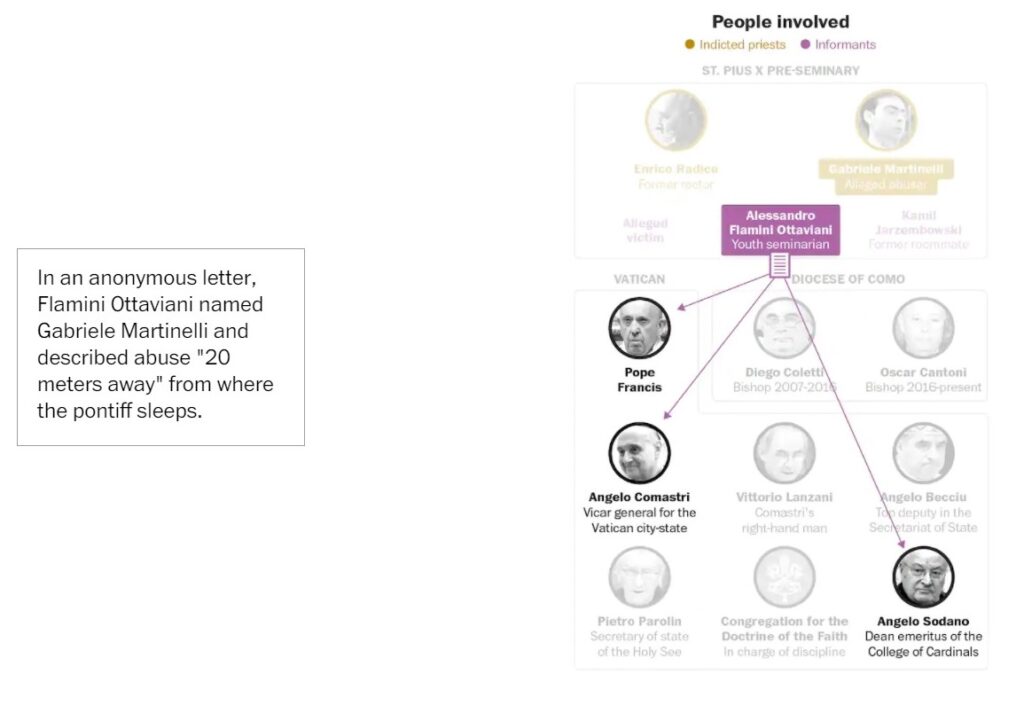

“Right now a boy is there who should no longer be there,” read an anonymous letter sent to Pope Francis and several cardinals in 2013, informing the just-elected pontiff of an alleged offender “20 meters away from where you sleep.”

The alleged abuser had even participated in the pontiff’s first Mass in the Sistine Chapel.

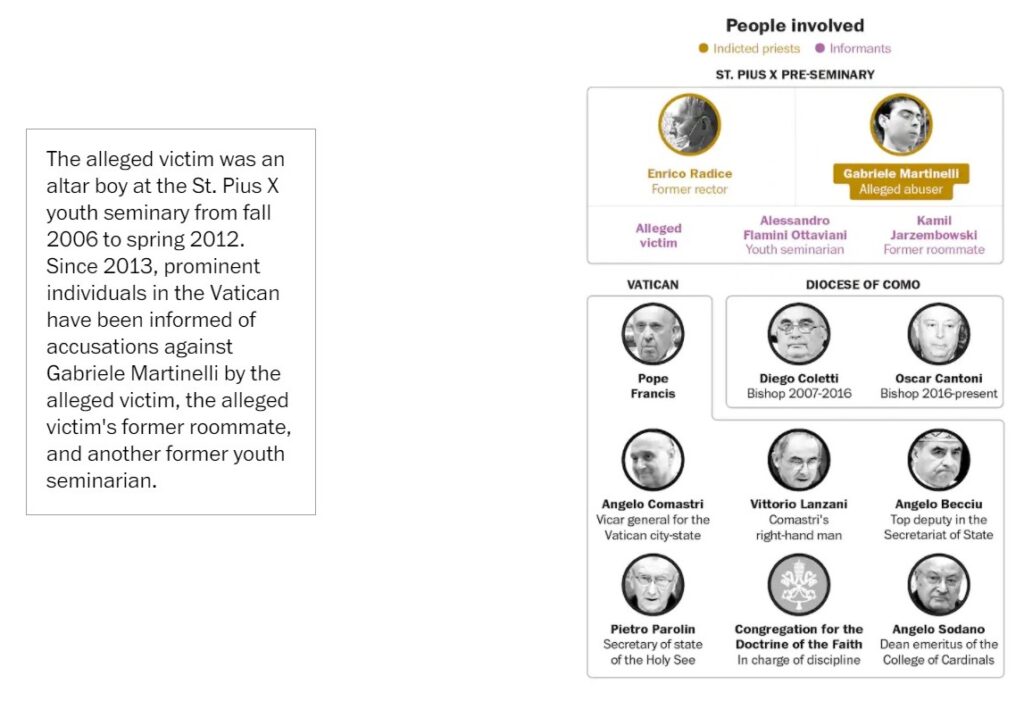

For a church trying to better contend with abuse and coverup across its empire, the warnings about Gabriele Martinelli were a direct institutional test. The events described in the anonymous letter, as well as in accounts from the alleged victim and a witness, were said to have taken place right under the church’s nose. By 2013, the complaints about Martinelli had been communicated to the pope and a who’s who of cardinals and bishops. The next year, the Vatican’s third-ranking official wrote a letter that referred to the accusations and asserted that the pope “knows the case well.”

And yet, in 2017, Martinelli was ordained a priest.

That outcome “was damned wrong,” said Kamil Jarzembowski, a former altar boy who said in an interview that he witnessed his onetime roommate being abused by Martinelli “dozens and dozens” of times.

Only after Martinelli’s ordination — in the wake of Italian media coverage — has the Vatican revisited the case. It has put Martinelli, now 28, on trial on charges related to alleged sexual abuse — the first time the city-state has prosecuted such a case on its own territory. The former rector of the youth seminary, the Rev. Enrico Radice, is also on trial, accused of aiding and abetting the alleged abuse. Martinelli and Radice both deny any wrongdoing.

But a Washington Post review of more than 2,000 pages of documents, most never previously reported, reveals that more powerful figures within the church hierarchy discounted warnings as they facilitated Martinelli’s rise. Centrally responsible for Martinelli’s fate were Cardinal Angelo Comastri and Bishop Diego Coletti, who quickly dismissed the claims against Martinelli as “calumny,” according to Coletti’s own account. Neither prelate is involved in the trial or any other known church disciplinary process.

The documents The Post obtained include church letters, police interviews, witness statements, and transcripts of conversations taped by Martinelli and pulled from his phone. Some of those documents come from the Vatican and are based on interrogations in the run-up to the trial, which started last year. Other documents come from judicial authorities in Rome who have also pressed charges against Martinelli and Radice on the grounds that they are Italian citizens.

This account, based on those documents as well as on interviews, is the anatomy of a failure at the very center of the Catholic Church. The failure stems not just from the often-reported factors that typify church coverups — a preference for secrecy, a desire to guard against scandal — but also from a struggle by church authorities to conduct credible investigations and to understand aspects of power, sexuality and consent in a teenage world.

The Vatican declined to respond to a list of questions from The Post or to accept an invitation to share the Vatican’s view on key aspects of the case.

One high-level church official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to summarize internal church thinking, said the Vatican had believed Martinelli “could not be accused of sex abuse” because he was just 221 days older than the fellow altar boy. People familiar with the case say this assumption was reflected in the church’s response to warnings and caused authorities to overlook a key factor in the relationship between Martinelli and the alleged victim: Martinelli had the power.

A protege of the rector, Martinelli had a role unlike that of any other teen at St. Pius X youth seminary, as the facility is known. He doled out assignments for papal Masses, selecting which teens would stand directly in front of the pope or to his side — with the chance to join the pontiff afterward in the sacristy. Among the middle-schoolers and high-schoolers who had left their homes and families with an aspiration to serve the pope, Martinelli was seen as the papal gatekeeper.

“He would exploit the circumstance and exercise a sort of dominion over the other youngsters,” one cleric, Ambrogio Marinoni, told a church investigator after Martinelli had been made a priest.

The alleged victim, through his lawyer, declined an interview request from The Post, citing the ongoing trial. (The Post does not publish the names of alleged victims of sexual abuse.) However, he has provided consistent accounts in letters, in a brief unpublished memoir, in 2018 legal charges filed at the Vatican, and in a 2019 interview with a prosecutor in Rome.

Those accounts describe prolonged abuse beginning months after the alleged victim, then 13, arrived at the youth seminary in 2006. On the first such night, Martinelli, then 14, allegedly climbed into the fellow altar boy’s bed, pulling down his underpants and submitting him to oral sex, while masturbating.

The alleged victim recalled feeling “petrified” and unable to react.

He said Martinelli kept coming back — hundreds of times over six years. The alleged victim said he occasionally fought back, or tried to make noise, pounding a bedside table or punching a wall, hoping to scare Martinelli off and draw a supervisor’s attention. But he said he was also terrified of being labeled a homosexual, losing his spot at the seminary and being sent back to his northern Italian hometown, where his home parish calendar showed a photo of him standing next to the pope. Because of Martinelli’s status, the alleged victim said, the sexual activity became “a ritual I could not resist.”

According to the former altar boy, Martinelli even emphasized his power during sex acts, saying things like, “Come on, I’ll let you serve Mass. I’ll be quick.”

The alleged victim said he was abused more frequently in the run-up to celebrations involving the pope.

A botched investigation

The first missed opportunity for the church to assess what may have happened came in 2010, when the alleged victim tried for the first time to alert an authority figure. In this instance, he said, he vaguely told the rector, Radice, that Martinelli had been “bothering” him. But according to the alleged victim’s account, Radice threatened to send him home and inform his parents if he didn’t stop repeating “falsehoods.” The alleged victim said he didn’t try telling another authority figure during his final two years at the youth seminary.

The church’s second chance to deal with Martinelli came from a far clearer set of warnings in 2013. The explicit anonymous letter, sent to the pope and several cardinals, quickly made its way around the Vatican and opened a window into the case.

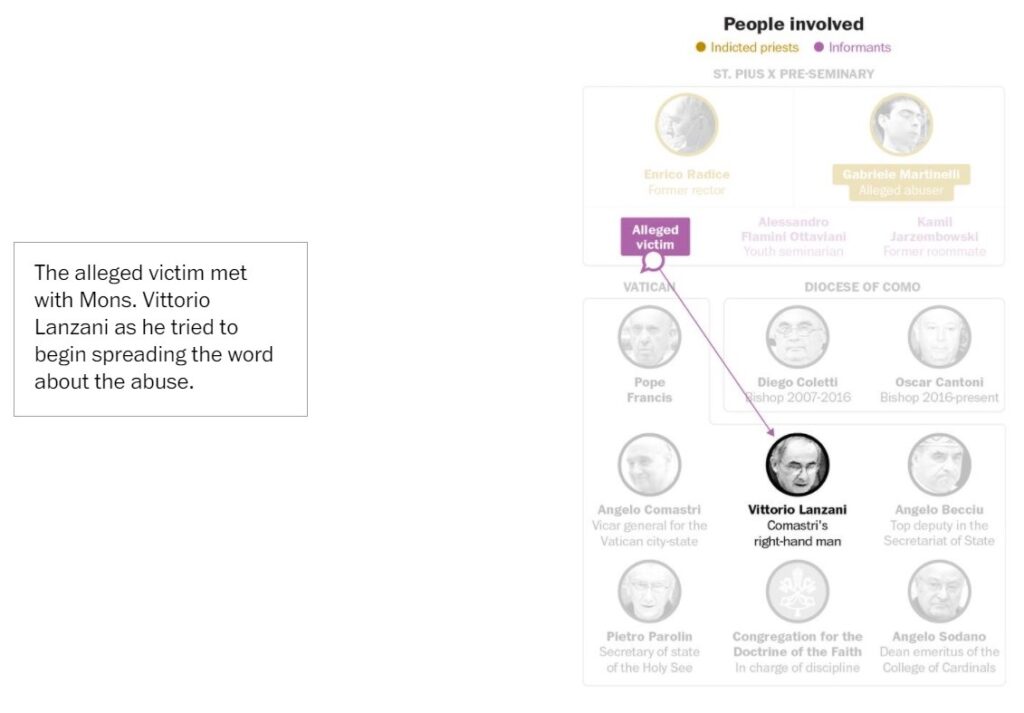

Around the same time, the alleged victim sought to speak out. By that point, he was no longer an altar boy, but he remained in the church’s orbit, singing in a St. Peter’s Basilica choir. He met with a couple figures inside the Vatican, and his accusations were relayed at least as high as Comastri, who as vicar general was in day-to-day charge of the city-state’s spiritual affairs.

Comastri wrote that the youth seminary needed to “start with a fresh page” and new leadership, but he largely left the matter to someone else: Diego Coletti, the bishop of Como, a large diocese 400 miles northwest of Vatican City.

Because of a historical quirk, the youth seminary was run by a small Como-based priestly association, known as the Opera don Folci, whose founder, a friend of Pope Pius XII’s, had been asked in the mid-1950s to establish a pipeline for aspiring priests inside the Vatican.

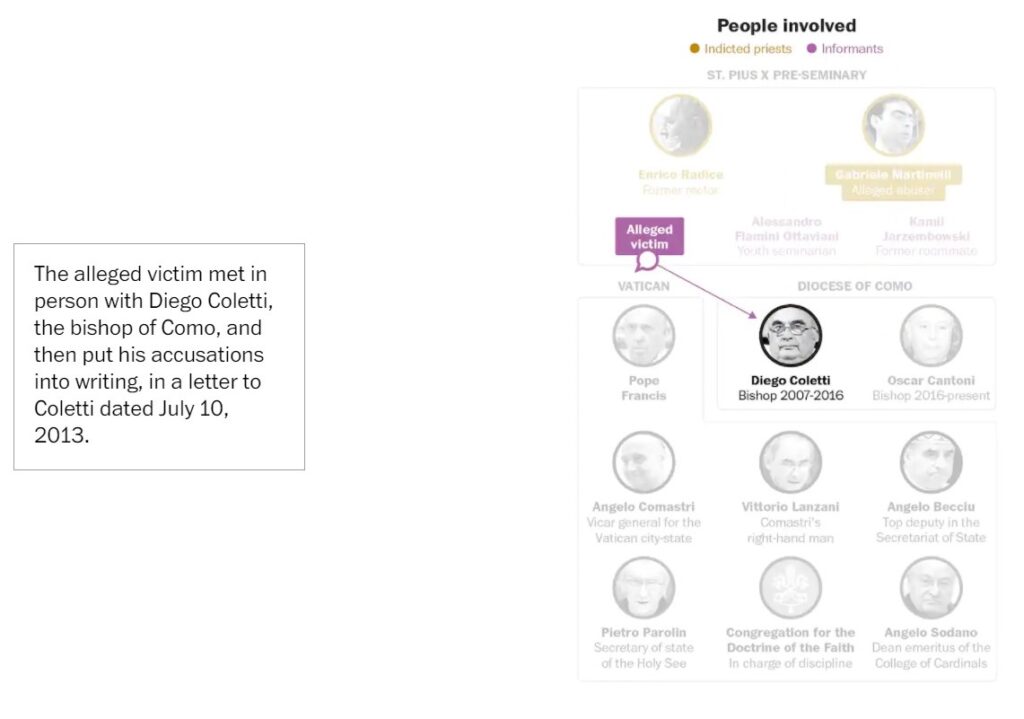

In the eyes of some of the altar boys, it was not Coletti in Como but rather Comastri at the Vatican who stood as the ultimate authority figure. And yet it was Coletti who met face-to-face with the alleged victim in July 2013 and who asked him to put his experiences in writing. It was Coletti who received the resulting letter — a detailed account in which the alleged victim wrote, “To this day, I happen to wake up suddenly at night, scared, feeling like there is someone lying in my bed.”

And it was Coletti who read that letter and never responded, according to the alleged victim.

Instead, the bishop relied on the word of the alleged abuser and the youth seminary’s rector, who both denied the claims outright, according to documents from Martinelli and Radice collected by Roman prosecutors. Martinelli and Radice told the bishop about rivalries within the school that might explain why abuse claims would be concocted. Three months later, Coletti traveled to the Vatican to meet with Comastri and essentially close the case.

In Coletti’s account of events, which he wrote up soon after the trip, he found the environment at the youth seminary to be “optimal.” He said there was “no evidence whatsoever” for the claims. He echoed Martinelli and Radice in suggesting that the accusations stemmed from competition among cliques, as well as the behind-the-scenes influence of a particular priest, who he concluded had written the anonymous letter. He said he had received from Comastri “confirmation of the machinations and of the calumny underlying the allegations” and that Comastri had asked him to dismiss the case.

“So I believe in conscience there is no need to proceed any further,” he wrote.

One of Coletti’s lieutenants later said the group found no evidence only because they hadn’t bothered to look. Coletti had traveled to Rome with Andrea Stabellini, at the time the top judicial official in the Diocese of Como, who believed that the accusations against Martinelli merited an “in-depth analysis.” But instead, Coletti spent his time in Rome gossiping about clerics and altar boys, Stabellini later told Vatican prosecutors, according to a transcript of his statement obtained by The Post.

“We did not even brush the topic of whether the alleged facts of abuse had actually taken place,” Stabellini said.

Coletti would turn out to be wrong about the anonymous letter. It was written not by a priest but by Alessandro Flamini Ottaviani, a fellow youth seminarian who’d heard secondhand of the alleged abuse and who later said he’d been reluctant to give his name.

Stabellini said the prelates, while at the Vatican, did not speak with any of the altar boys, including the alleged victim. He said that a final, closed-door meeting of Comastri, Coletti and the rector had lasted “all of five minutes.” While Stabellini waited outside, another priest, Marinoni, whispered to him that the case had merit.

“When the meeting between the three was over, I addressed Bishop Coletti with a quizzical expression,” Stabellini told Vatican prosecutors.

He recalled Coletti’s saying, “Now, the matter is closed.”

He recalled Comastri’s saying that the investigation had been ended “for the sake of the church.”

On the way to priesthood

Martinelli moved on to the Pontifical French Seminary, a well-known clerical training ground blocks from Rome’s Pantheon. Although he had been effectively cleared of wrongdoing, church documents suggest Vatican officials still felt the need to keep a close eye on him.

“I ask you the courtesy of taking special care to the aforementioned seminarian,” then-Bishop Angelo Becciu, the Vatican’s third-ranking official at the time, wrote to the incoming French seminary rector in a note that made reference to the abuse accusations. Becciu said his request came “in the name of the Holy Father Francis, who knows the case well.”

(Becciu, who was removed by Francis from his position last year, faces charges of embezzlement and abuse of office in an unrelated financial case and will face a Vatican trial later this month.)

Martinelli, in the grand hierarchy of the church, was a nobody. But in his years at the youth seminary, he had become a fixture among church royalty. He also embodied something of value: He was a young, could-be priest. Of all the altar boys who had streamed through the youth seminary, only 200 or so had gone on to become clerics. Even fewer had signaled a willingness to become priests for the Opera don Folci, the association that ran the seminary.

The Opera had once been a powerful, well-funded group. But it had dwindled to roughly a dozen mostly-elderly clerics who operated in a northern Italian region with a dire shortage of priests. That’s where Martinelli would serve, too, if ordained. Radice, the rector, who was also a member of the Opera, would later describe Martinelli during the trial as a leader in the making.

To provide updates on Martinelli’s progress, the French seminary sent end-of-year letters to the Como Diocese, marked “confidential.” Those notes amounted to report cards, describing Martinelli as learning French, volunteering at a hospital and with a scout group, having “good brotherly relationships” with his fellow aspiring priests. But they also showed how the initial conclusions of Comastri and Coletti took hold as time went on.

“A lingering question mark concerns the grave accusations,” the French seminary’s rector, Antoine Hérouard, wrote in 2015.

“It’s ever more likely that the suspicion raised … some years ago turned out to be groundless,” Hérouard wrote the next year.

The documents reviewed by The Post reflect one other accusation of sexual misconduct by Martinelli. Several witnesses told Roman and Vatican authorities that they saw Martinelli touch the genitals of another teen at the youth seminary. Martinelli told Vatican prosecutors this “may have happened” involuntarily during a game.

But as there was no known pattern of sexually predatory behavior, church officials came to the conclusion that the original accusations must have been false.

During Martinelli’s time at the French seminary, the Vatican took only one special measure to gauge his readiness for the priesthood: It submitted him for a psychiatric evaluation. That unusual step was aimed at teasing out any problematic behaviors, including sexual issues. But it was not a tool for determining whether Martinelli had committed any crimes, Hérouard said in an interview with The Post. The evaluation did not find any psychiatric problems. The finding, according to Hérouard, helped lift Martinelli’s mood.

Hérouard wrote at the time to the Como Diocese that the accusations were “fading away.” But that was in part because the alleged victim had cut off contact with the church, feeling betrayed by its officials. According to a psychological evaluation submitted for the trial, he was racked by night terrors and panic attacks that repeatedly sent him to the emergency room.

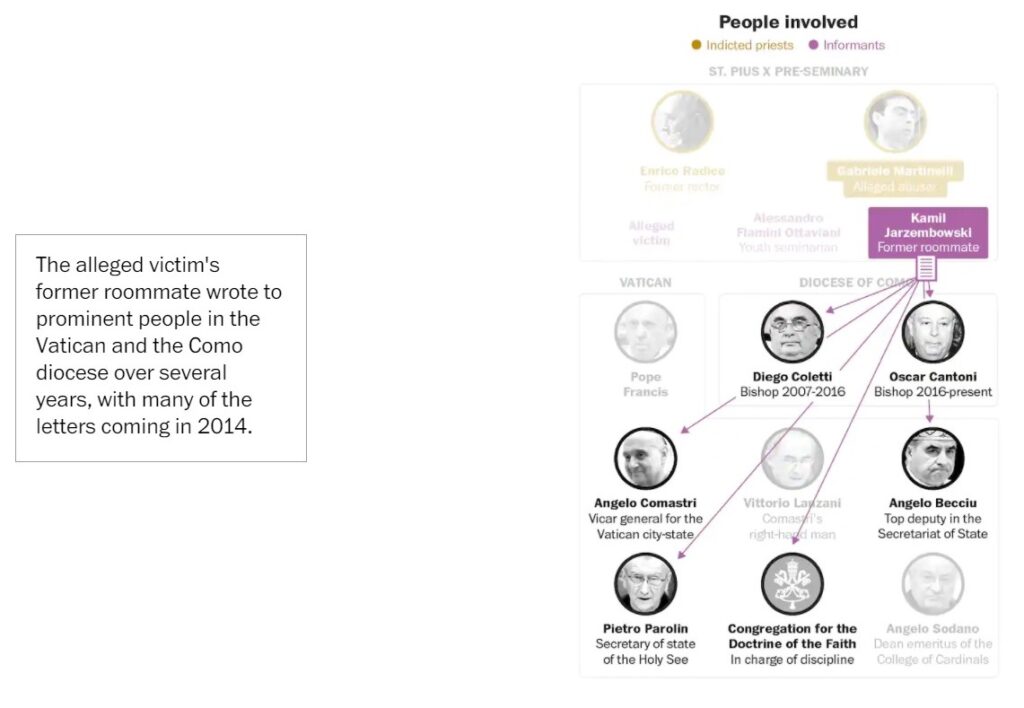

There was only one person who continued to sound the alarm: Jarzembowski, the former youth seminary roommate.

Jarzembowski, from rural Poland, had written a letter to Comastri soon after the short-lived 2013 inquiry, warning about Martinelli. He said in an interview with The Post that he’d hoped it would prompt the Vatican to reexamine the case. Instead, one day after a 2014 in-person meeting with the cardinal, Jarzembowski said, he was ordered to pack his bags and leave the youth seminary.

Neither the Vatican nor the Como Diocese responded to a question about why Jarzembowski was removed. Jarzembowski said he received no official reason. The head of the Opera, during the trial, said Jarzembowski was removed for failing to obey the rules after briefly running away from the youth seminary a year earlier. An Opera document from the year of Jarzembowksi’s removal, assessing his time at the youth seminary, contained several homophobic passages and implied that Jarzembowki’s friendship with other young men was one of the problems. It described his “intense” and “too obvious” bond with one classmate, who was “the reason for his life,” and also presented him as leading others “down the same path.”

Jarzembowski’s removal as an altar boy, at age 18 and with a year to go before high school graduation, left him feeling directionless and so estranged from the church that he’d eventually renounce the faith. He started agitating in every way he could.

Four days after his removal, he wrote to Coletti with an account of how Martinelli had repeatedly come into his room and coerced oral sex from his roommate. Nine days after that, he wrote a similar letter to Becciu. Then he wrote to Stabellini, the Como investigator. And to Comastri again. And Coletti again.

To the extent that he received responses, they were dismissive. “Cheer up and put your heart at peace,” Comastri wrote.

Jarzembowski kept going. His letters became not just records of what he said he had witnessed but also a log of whom he had informed. He wrote to the head of the Opera, a priest named Angelo Magistrelli. He wrote to the Vatican’s second-ranking official, Cardinal Pietro Parolin. He wrote to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican’s disciplinary office. He wrote to the rector of the French seminary, where Martinelli had arrived. And, as Coletti neared retirement, he wrote to Coletti’s incoming replacement, the bishop who would take over the Como Diocese and oversee Martinelli’s potential ordination.

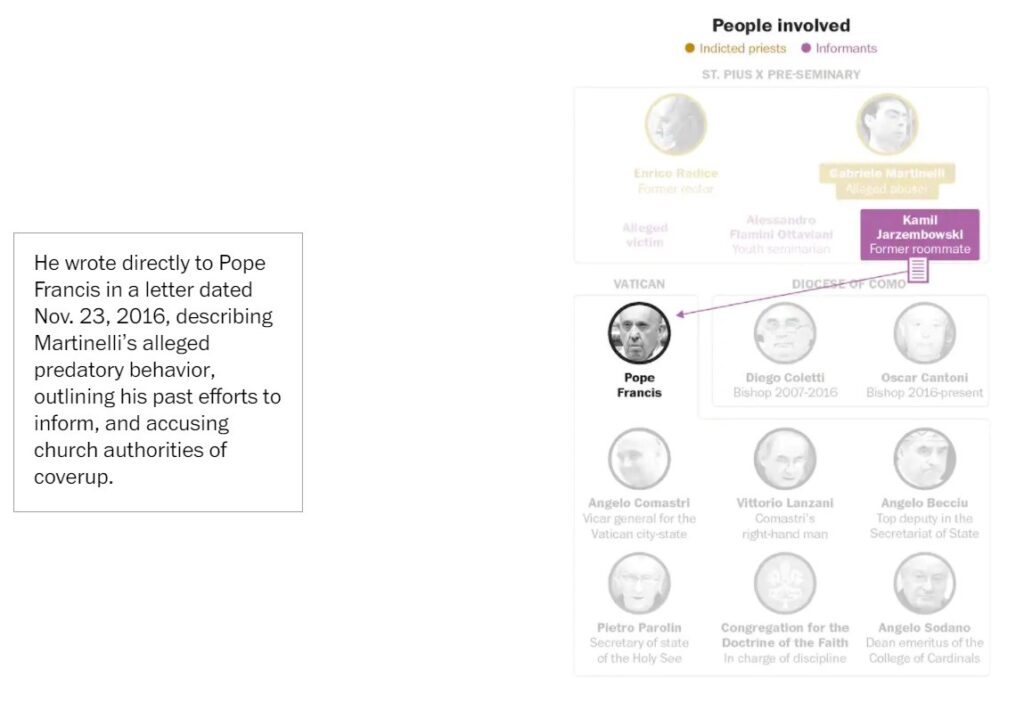

He also wrote directly to Pope Francis.

“During my direct meetings or correspondence [with church authorities], none of them showed they would deal with the reported case by investigating,” Jarzembowski wrote to the pope in November 2016. “No one worried about ascertaining and evaluating facts, showing instead the will to ignore them, or worse, cover them up.”

Seven months later, in a ceremony led by the new bishop of Como, Martinelli was ordained a priest.

A partial reckoning

The Rev. Gabriele Martinelli was quickly put to work by the Opera in a northern Italian valley of small communities strung along a highway, closed in on both sides by mountain ranges. All across the valley, there were decommissioned churches and dwindling congregations, and Martinelli was welcomed as a rare injection of youth. He started leading Sunday services. He managed youth programs. He took part in a community chestnut festival and organized a Halloween celebration where the children dressed as saints.

Martinelli could have made a career in that valley, the allegations drifting further into the background, were it not for Jarzembowski, who recalled in an interview feeling sickened and grasping for options.

“I’d been trying to resolve the matter inside the church,” Jarzembowski said. “After years, they never responded. So I thought, ‘What can I do?’ ”

What he did was take his letters to an Italian journalist, Gianluigi Nuzzi, who in turn also referred Jarzembowski to a broadcast reporter, Gaetano Pecoraro. That led to separate, near-simultaneous reports — Nuzzi’s in a book, Pecoraro’s in a TV program — that publicly exposed the accusations against Martinelli five months after he’d been ordained. Both accounts described Jarzembowski’s efforts to raise the alarm and named Coletti and Comastri as being involved in a potential coverup. Pecoraro’s broadcast, on the program “Le Iene,” included a concealed-identity interview with the alleged victim.

The Vatican said publicly that a new investigation was starting “in light of new elements that have emerged.”

Soon after, Martinelli told parishioners he was going on a spiritual retreat. The diocese barred him from contact with minors, according to church documents.

“He was here barely long enough to get to know him,” said Gian Pietro Rigamonti, 71, another Opera priest.

The documents reviewed by The Post provide a more detailed understanding of the actions of church figures behind the scenes — both before and after the Italian exposés.

What followed the 2017 broadcast was a partial, and mostly secretive, reckoning, in Como and at the Vatican. In the days after the broadcast, several priests formerly assigned to the youth seminary approached the new bishop of Como, Oscar Cantoni. According to a written account by Cantoni, the priests told him they had believed the accusations against Martinelli but had been told by Radice to stay silent. The new bishop of Como asked for permission from Becciu, a close lieutenant of Francis’s at the time, to reinvestigate the case.

The result of that investigation was a 21-page document sent to the Holy See but not made public. The document — among those obtained by The Post — was sharply critical of church missteps in the Martinelli case while also positing unscientifically about aspects of consent and teenage sexual development. The review blistered Coletti, saying his inquiry had been skewed by bias and was “superficial at best.”The review said the core of the alleged victim’s claims were “reliable” and “coherent.” But it also concluded that Martinelli’s behavior, though inappropriate, was understandable for adolescents, for whom there is often “no perfect match of wills.”

“The behaviors were just the expression of a transitory homosexual tendency, of a not-yet-completed adolescence,” Cantoni wrote at the end of the review.

Simon Hackett, a professor of child abuse and neglect at Durham University in Britain who studies the issue of sexual offending in childhood, responded to summarized aspects of the case at The Post’s request and said church authorities seemed to be searching for ways to explain away the problem — while getting sidetracked by the issue of homosexuality rather than focusing on potential abuse.

“The association of homosexuality, a legitimate form of sexual behavior, with sexual abuse is deeply problematic,” Hackett said.

The trial, which has been open to a small pool of reporters, is looking at whether Martinelli’s behavior was not just inappropriate but also criminal. In intermittent courtroom dates amid the pandemic, more than a dozen figures have offered testimony, including the alleged victim and his former roommate, Jarzembowski.

Martinelli, who has been living out of public view in an Opera-run nursing home, surrounded by people decades older, took the stand at one point and called the charges unfounded. Radice also denied any wrongdoing.

Some former students say they witnessed no abuse. Others described an institution out of control, where oversight was lax and students joked constantly about homosexuality and gave one another female nicknames.

“The environment was basically unhealthy,” said Flamini Ottaviani, who stayed at the youth seminary for only a year.

There is no record indicating that Pope Benedict XVI, pontiff when the abuse allegedly took place, was aware of the accusations. With Francis, there is conflicting information about how involved he was.

Although a cast of prelates below him appeared to be dealing with most aspects of the case, Martinelli in 2017 said the pope had personally ordered the psychiatric evaluation. “It was the pope himself,” Martinelli said in a conversation that he recorded and was later pulled from his phone by Roman investigators. In another recording, a man referred to as “the Rev. Angelo” — identified by the police as likely being Opera leader Angelo Magistrelli — told Martinelli that the pope had encouraged his advancement to the French Pontifical Seminary and had believed the accusations to be “calumny.” Magistrelli declined numerous interview requests.

The Vatican did not respond to a question about the pontiff’s role, or about whether his thinking on the case had changed. In July 2019, Francis wrote a special provision allowing the trial to go forward, circumventing statute-of-limitations constraints. In May, the pontiff also announced that he would move the youth seminary outside the Vatican city-state, a decision the Vatican said is not connected to the trial.

From witnesses on the stand, the names of Bishop Coletti and Cardinal Comastri have both come up repeatedly. But neither is a focus of the trial, and neither is expected to testify. The Vatican did not respond to questions about Coletti’s or Comastri’s roles.

Francesco Zanardi, who has been following the trial as the head of an Italian church-abuse victims’ group, said it was “scandalous” that the two prelates were not under closer examination by the church. Zanardi called Radice, the former seminary rector who is facing charges of aiding and abetting, “just a scapegoat.”

The church, some three decades into its sexual abuse crisis, has often been more willing to punish low-level priests than higher-ups who do not react scrupulously to information they receive concerning possible abuse. In the church’s hierarchy, bishops and cardinals are responsible only to the pope, and the Vatican has struggled to draw up an effective system in which prelates can provide checks on one another. The church has sometimes refrained from disciplining prelates who are already at or near retirement age. And sanctions, when they are applied, tend to be administered privately, without explanation from the Vatican.

Jarzembowski said he holds both Coletti and Comastri “morally responsible.”

“You had a group of 15 boys that you needed to protect, and you failed,” he wrote to Comastri in 2019.

Coletti, 79, is absent from the trial because his doctor said he is unwell. Paperwork submitted to Vatican judges said that Coletti, though still able to live his day-to-day life, was experiencing a form of “cognitive decay,” as well as diabetes.

He is spending his retirement north of Como, in the annex of a 12th-century church, with a garden and two donkeys. Residents in his neighborhood said Coletti is still active in the community, walking in the early evenings, taking confession, and leading Mass with the help of an assistant. A woman who answered the door at Coletti’s home said the bishop wasn’t there and would be gone for “days.” She refused to take any message for him.

The Diocese of Como, reached separately, did not make Coletti available for comment. Nor did the diocese respond to questions seeking more details about Coletti’s mental state.

Comastri, 77, in February left his position as the Vatican’s vicar general — a step some insiders speculated might be a response to the trial. But Comastri told The Post that it was just a normal retirement, not a punishment. He continues to hold rosary services inside St. Peter’s Basilica, posing for photos and blessing babies after the midday ceremonies.

“A priest never retires,” Comastri said in a brief conversation in the sacristy.

Before ending the interview, Comastri reasserted that the Martinelli case had been handled appropriately. He said that the main responsibility fell to Coletti, anyway, and that the allegations — which he said stemmed from “jealousies” — were not credible.

“In my judgment, there are no serious allegations here,” he said.

About this story

Story by Chico Harlan and Stefano Pitrelli. Graphics by Artur Galocha. Photos by Chiara Goia, Stefano Pitrelli/The Washington Post, Vatican Media, Giuseppe Lami/Pool/AP, Fabrizio Cusa, Osservatore Romano/Getty Images/AFP, Alessandro Di Meo/EPA/Shutterstock, Gregorio Borgia/AP, Richard Drew /AP, and Andreas Solaro/AFP/Getty Images. Project editing by Marisa Bellack. Photo editing by Chloe Coleman. Design and development by Emily Wright. Copy editing by Gilbert Dunkley and Martha Murdock.

Chico Harlan is The Washington Post’s Rome bureau chief. Previously, he was The Post’s East Asia bureau chief, covering the natural and nuclear disasters in Japan and a leadership change in North Korea. He has also been a member of The Post’s financial and national enterprise team.

Stefano Pitrelli is a reporter in the Rome bureau for The Washington Post.