(PA)

NorthJersey.com [Woodland Park NJ]

September 20, 2021

By Deena Yellin

Leaving Religion, Keeping Faith

[Photo above: Patty Bear during pilot training. When a representative of the Air Force Academy spoke at her school, she realized she’d found her ticket to freedom. – Courtesy of Patty Bear]

Patty Bear began plotting her escape in high school.

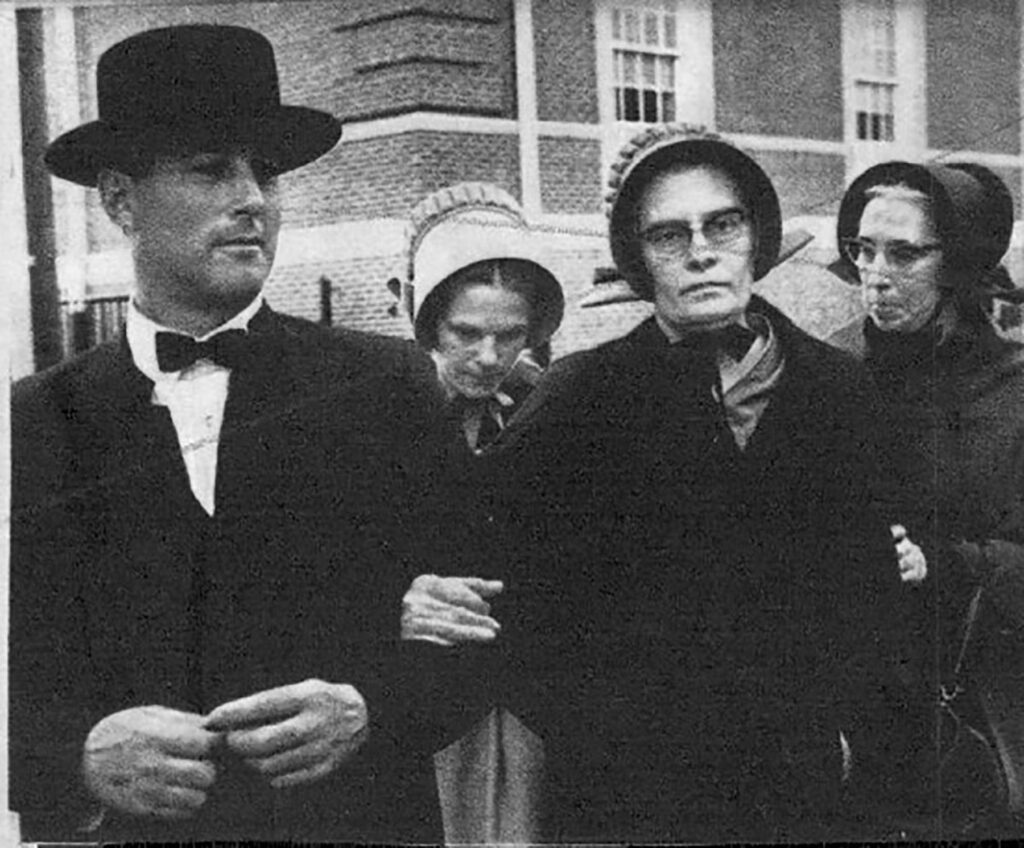

Raised in a strict Reformed Mennonite community in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Bear was trained to become a wife, mother — and little else. “My mother wore long dark dresses and a white bonnet,” the 57-year-old recalls. “And I was expected to grow up and wear the same uniform.”

There was a darker side, too, Bear said, to a society where women were taught to be “submissive and obedient.” She endured years of emotional and physical abuse at her father’s hands, she said, forcing her mother to take Patty and five siblings on the run.

Bear would eventually leave the church, become a U.S. Air Force pilot and fly commercial jets around the globe. At home now in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, she says she considers herself spiritual, but has no taste for religion.

“I have religious PTSD,” she quips.

Her journey was extreme, but the destination is familiar for the many Americans leaving organized religion every year. Bear is among the 26% of U.S. adults who do not identify with any particular faith, a group growing faster than any religious sect in the nation.

The “Nones” give many reasons for breaking away. For some, abuse has played a key role — whether it’s the trauma of individual assaults or disillusionment with institutions like the Catholic Church, which has been rocked by tales of sexual abuse and official cover-ups.

A 2019 survey by Gallup found that only 31% of American Catholics rated the honesty and ethical standards of clergy as “high” or “very high.” That’s down from 63% in 2008.

“After 12 years of Catholic school, I do not attend Mass anymore, and the primary reasoning is the sexual abuse crisis and the cover-up from the hierarchy that remains to this day,” said Bruce Novozinsky, a New Jersey man who says he was the victim of attempted abuse as a child.

“I believe in the power of prayer and the complete Being that is God. I just don’t believe that I need a brick-and-mortar building to spend time in and speak to Him (which I do every day),” he said in an email.

Catholicism isn’t the only faith seeing erosion. A survey this spring found that fewer than half of American adults belong to a house of worship, the lowest in almost a century of Gallup polling on the question.

IN U.S., BELIEF IS ‘TAKING A NEW FORM’

Torah Bontrager, 40, grew up in an Amish community in the Midwest, where she says she suffered emotional and sexual abuse at the hands of teachers and relatives. She eventually left, spent years in therapy and now runs the Amish Heritage Foundation, a nonprofit that helps other former worshippers trying to leave.

“You don’t need religion to be a good person,” she said.

“There is still a lot of belief and spirituality, but it’s taking a new form,” Ronald Inglehart, a retired University of Michigan professor and author of “Religion’s Sudden Decline,” said in an interview this summer.

“Americans who grew up in recent decades in a society where no one starved are less reliant on the comfort of religious rituals than their ancestors were,” said Inglehart, who died in August. Social media, meanwhile, makes it easier for people to establish communities without the aid of a church.

Pop culture has enjoyed a fascination in recent years with religious communities like the Amish and Mennonites, the so-called “Plain People” known for their old-world charm, tight-knit families and austere lifestyles. Bontrager and Bear recently published memoirs, joining an array of accounts on bookshelves and TV screens about people who fled strict religious upbringings.

“People need to see there’s a path out there,” said Bear.

She said her abuse began when she was 8 and her father, Robert, was shunned by his Mennonite brethren for repeatedly challenging church leaders over doctrine. Neighbors and relatives refused to associate with him, a painful rejection employed by the community to punish errant members.

Her father’s shunning made national news after he went to the media with his story. Robert Bear was portrayed sympathetically in many articles as a devoted father and husband who’d been wronged by his church.

The true story involved a man who “terrorized” his family for years, Patty Bear wrote in her book, “From Plain to Plane: My Mennonite Childhood, a National Scandal and an Unconventional Soar to Freedom.”

The family eventually went on the run but could never escape for long, Bear said. Her father tracked them down, broke into their new homes and dispensed verbal and physical blows.At one point, Patty Bear said, he kidnapped her mother and sister.

Robert Bear was arrested but acquitted of the abduction by a Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, jury in 1979, according to media reports.

The traumatic experience made Patty realize she wanted a “different life than what I had been born into,” a world in which church members were forbidden to own televisions, go to the movies or press charges if they were robbed.

Robert Bear, 92, still lives in Carlisle. In July, he was arrested on vandalism charges after he allegedly stapled copies of a “manifesto” to a Reformed Mennonite church.

In a brief telephone interview, Robert Bear said he never got “to write my part of the story” and that “the media doesn’t want to hear what I have to say.”

“They lied [about] me,” he said of the Reformed Mennonite Church.

STRUGGLING TO HOLD ON TO FOLLOWERS

The Mennonite and Amish communities share common roots in the Anabaptist church, which baptizes adults when they declare their faith. The two groups share a strong belief in pacifism and deliberately distance themselves from the mainstream culture.

Established in 1812, the Reformed Mennonites are among the most conservative offshoots of that tradition. The church has struggled to hold on to members, declining from 2,000 in 1900 to just 350 in 2019, according to the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania.

The Amish enjoy higher birth and retention rates and have seen their numbers grow. Still, leaving can be traumatic. Defectors risk shunning and permanent excommunication from friends and family.

The lifestyle can also have a strong appeal, offering a sense of purpose and protection. Bear has happy memories of growing up with her five siblings on a bucolic 400-acre potato farm, reading the Bible and attending church.

Bontrager learned to be self-sufficient in a culture where children are taught at a young age to grow, preserve and can their own food, to raise animals and to hunt in the wild. There was a spirit of togetherness that’s hard to duplicate, she said.

“If you ever needed help, people would be there for you.”

But for both women, the bad outweighed the good.

Bontrager was an avid reader who loved learning, but her formal education stopped in eighth grade, since the Amish prohibit high school education. She said she was discouraged from questioning and beaten for being too curious.

“I cried when I graduated,” Bontrager said.

At age 11, she tried to leave home but was caught and punished. On her second attempt, at age 15, she climbed out a bathroom window in the middle of the night. She arranged to stay with an uncle who had left the community years earlier. Eventually, she achieved a dream of graduating from high school and went on to earn a philosophy degree at Columbia University.

Her memoir, “Amish Girl in Manhattan,” was published in 2018.

Bear had been thinking about leaving even before the kidnapping attempt. She was disenchanted with the rigid destiny that seemed carved out for her.

“I looked at the little breads my mother was frantically making and thought, `How can she feed six kids with this?’ I realized I never wanted to be in that position and decided I would go to college, which was at odds with our community.”

Bear signed up for classes she would need to get into college. At her older brother’s suggestion, she also took flying lessons. When a representative of the Air Force Academy spoke at her school, she found her ticket to freedom.

Her life today has little in common with the Mennonite girl who spent her days sewing, baking and canning at an early age to prepare for an inevitable future. She graduated from the academy and went on to command an aerial refueling tanker in the first Gulf War. She’s worked as a commercial airline captain and life coach.

A mother of two, she still keeps in touch with relatives in the Mennonite Church and even maintains a relationship with her father. Her mother, who died recently, left the church years ago.

Bear still believes in a higher power, she said: a “divine force which I think of in non-gendered terms… I call it ‘the Divine’ or ‘the Universe.’ ”

To her, spiritual maturity is about personal sovereignty — “following no gurus or religious authorities unquestioningly.” She said she expresses her beliefs through the way she treats people, the trails she blazes that she hopes others can follow.

“I think it’s part of human nature that we yearn for freedom. The question is: How much do we pursue it? How much do we dare to follow that? I am grateful for having the choices that I have today and that I have the ability to ask questions.”

Deena Yellin covers religion for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to her work covering how the spiritual intersects with our daily lives, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: yellin@northjersey.com

Twitter: @deenayellin