MADRID (SPAIN)

El País [Madrid, Spain]

December 18, 2021

By Iñigo Domínguez, Julio Núñez, and Daniel Verdú

[Photo above: Stills from the 5 1/2 minute video in Spanish by Luis Manuel Rivas and Antonio Nieto which accompanies this article. Left to right: Survivors Jesús Gutiérrez, Antonio Carpallo, and Emilio Boyer. Their stories are also discussed below.]

The Vatican supervises the entire process after the report that this newspaper has delivered to the Pope and the president of the Spanish Episcopal Conference, Cardinal Omella. The total number of victims thus rises to at least 1,237, but according to the testimonies collected, it could be thousands.

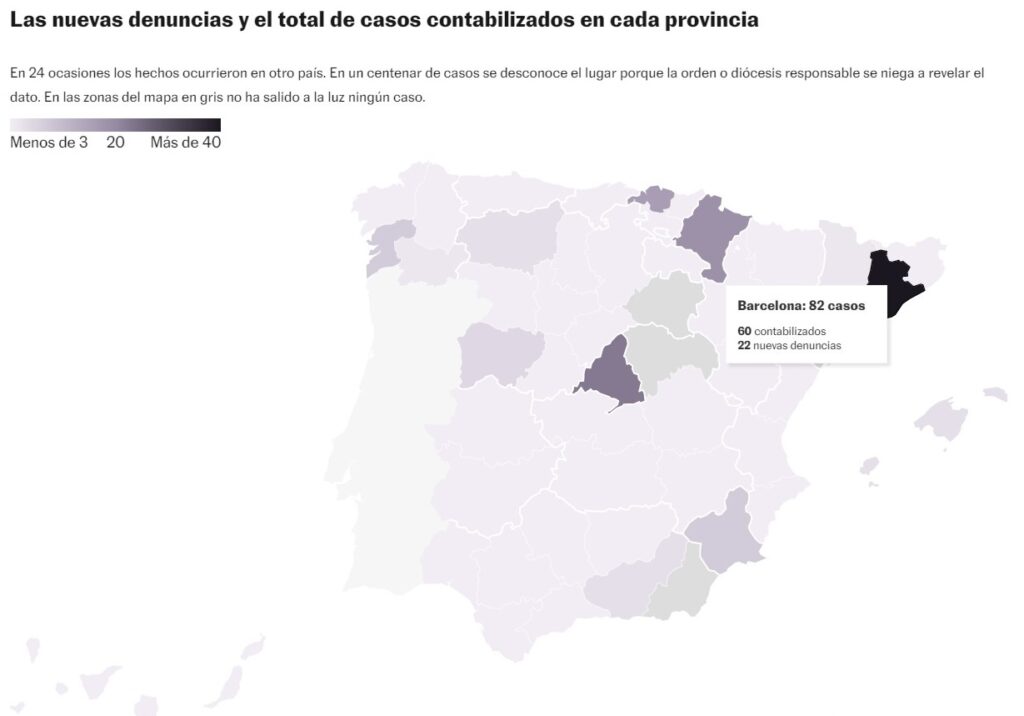

The Church has opened a large investigation, unprecedented in Spain, of 251 members of the clergy and some laymen from religious institutions accused of child abuse and that EL PAÍS has compiled and investigated in the last three years. They compose a 385-page report that this newspaper delivered to Pope Francis on December 2 last, taking advantage of the Pontiff’s direct contact with journalists on his trip to Greece. An assistant to Francis picked up the dossier and upon returning from the trip the Pope moved quickly. He sent it the following week to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the institution that centralizes the investigation of pederasty throughout the Catholic world and is directed by the Spanish Jesuit Luis Ladaria. This newspaper also delivered the study that week to the president of the Spanish Episcopal Conference (CEE), Cardinal Juan José Omella, archbishop of Barcelona. Omella immediately transmitted it to the ecclesiastical court of Barcelona, where it was registered, so that the investigation could begin, although later the investigations would have to branch out according to the competent entity: they affect 31 religious orders and 31 dioceses. The mechanism is already underway, although the opening of an investigation, in reality, is an almost automatic act required by the canonical code in the face of any plausible indication.

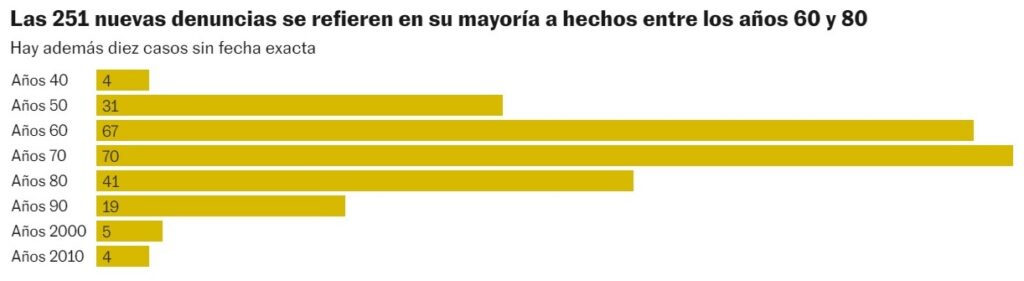

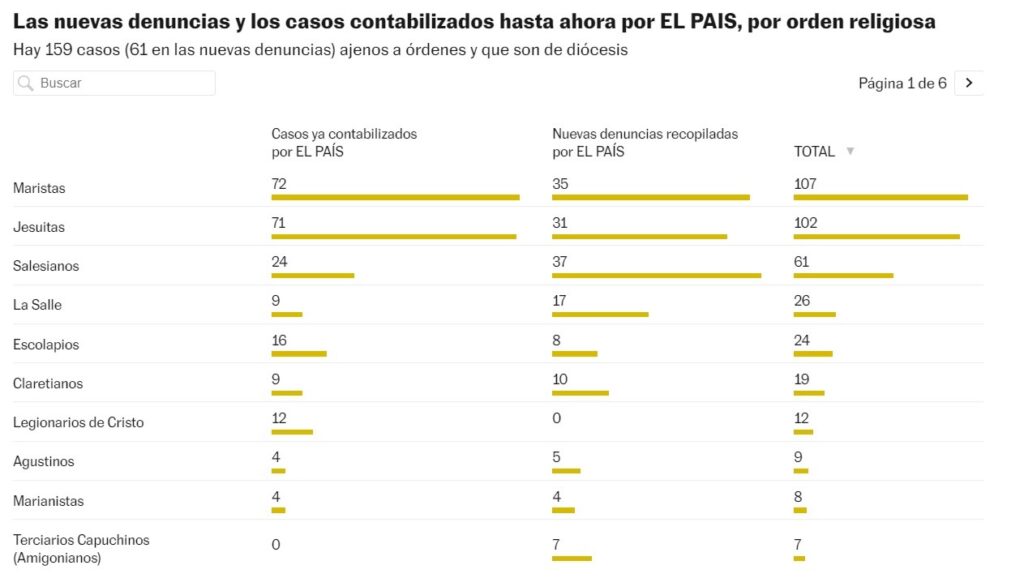

The oldest case in the report dates from 1943, and the most recent, from 2018. All are unpublished, except for 13 already published, which have been included because new complaints have arisen against these clerics. If those 251 are added to those that were already known until now and that this newspaper has counted, the only existing record in Spain. In the absence of official data from the Church or the authorities, they amount to at least 602 cases —each one refers to a defendant— and 1,237 victims since the 1930s. In any case, the strictest criterion has been applied to calculate the number of victims: only the direct testimonies of those affected and witnesses. In most of the stories there is talk of pederasts who abused dozens of children and behaviors that were an “open secret”. A common case is that of teachers who sexually assaulted the entire class, with several courses in charge and who spent years in one or more schools. Estimates such as those used by experts in the studies of independent commissions in other countries would multiply the figure to several thousand.

Until now the EEC has reiterated that it does not know how many cases of abuse have occurred in Spain, although it assures that they are “very few”. It is not going to open a general investigation and is limited to asking the victims to go to its attention offices, opened a year ago, but it assures that it has hardly registered complaints. On the contrary, EL PAÍS has already received more than 600 messages in the complaint email that it opened three years ago. Many of those cases have already been published, another 251 have been included in the report and the rest are still under investigation. The only figure provided by the Episcopal Conference had to be requested from the Doctrine of the Faith: it was informed this year that since 2001 it has received 220 cases from Spain. The EL PAÍS report collects more in three years than the congregation in those 20 and overflows those statistics.

Once the dossier of EL PAÍS was known, Pope Francis and Omella had a conversation. The Vatican, as it usually does when the complaints are so numerous and do not belong to a single order, diocese or specific abuser, will supervise the entire process carried out by the EEC through the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Rome will wait for results, which according to its own code, should arrive in no more than three months. The Episcopal Conference has preferred not to make any statements at the moment. On the other hand, the vast majority of cases, 77%, affect religious orders, which are not under the authority of the bishops. The main congregations, informed by EL PAÍS of the complaints concerning them, have already opened an investigation.

The Marists, one of the entities that accumulates the most cases, reacted like this through a statement from their Iberian province: “We condemn these terrible events and apologize to the victims for not having been able to protect them, to care for them and for not having adequately managed these situations. We have opened an investigation to clarify the events that occurred. The victims are our priority, we believe in their word and we make ourselves available for everything they need”. Most major orders spoke in similar terms, although some remain reluctant. For example, a person in charge who did not want to identify himself from the Zaragoza paúles, when exposing a case of his order, replied: “We will not investigate it. I have never heard anyone speak ill of this person. I am not interested in the subject. This is dirty.” La Salle also refuses to open a canonical investigation, as is his obligation, and has only specified that he has already transferred his cases to the Prosecutor’s Office, where their safe destination is to be archived as they are prescribed.

The regulations approved by Francis since 2019 to end the cover-up oblige any bishop or religious superior to open an internal investigation before any information about a possible case. The Vatican rules are very clear, summarized in the vademecum published in July 2020 . The information of a case, the notitia delicto, is “all information about a possible crime that reaches the Ordinary or the Hierarch in any way. It is not necessary that it be a formal complaint” (article 9). It can arrive in any way, also through the media (article 10). Even without precise data, it must be studied and if it is plausible to open a preliminary investigation (articles 13 and 16), which must then be sent to Rome, to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (article 69). Article 14 of the Pope’s motu proprio of May 2019, Vos est lux mundi , specifies that the investigation will last a maximum of 90 days.

All these norms have been disregarded in numerous cases in the Spanish Church by orders and dioceses, which when informed of a case limited themselves to saying that they did not know, did not open any investigation or inform the Vatican. Now they will no longer be able to do so, since the Vatican monitors the process and assures that it will guarantee that these cases delivered by El PAÍS will be investigated, the pertinent responsibilities will be assumed and the victims’ claims will be addressed. In many cases the defendants are still active and in this way the appropriate precautionary measures can be taken.

The investigation into the cases presented by EL PAÍS is currently limited to the canonical judicial route, and obviously, it means that the dioceses and religious orders investigate themselves. The EEC continues to refuse to create an independent commission to listen to the victims and promote a total review of the past. Other episcopal conferences have already launched them, in the United States, France or Germany. They are organizations that do not question the testimony of those affected —in most cases, the accused have died— and simply assess their credibility, gather their stories and obtain figures and conclusions of what happened. The number of complaints arriving in Rome from Spain, although it is somewhat lower than that of other countries, does not allow us to think that the situation could be very different from that of places like Germany or France.

In the report delivered to the ecclesiastical authorities by this newspaper, the personal data of the victims or references that can identify them do not appear, to guarantee their anonymity. In any case, EL PAÍS has made itself available to the Vatican to facilitate contact with the victims so that they can give a statement, if they so wish. The Holy See, after dozens of investigations and the summit on pederasty that Pope Francis convened in Rome in February 2019, assumes this type of process more normally. In fact, the Pontiff on Wednesday applauded “the dignity” of the French bishops for having carried out a historic investigation into abuses in the French Church.

Behind each of these figures there is a story, and in the oldest cases, a mosaic of what life was like in some schools and boarding schools during the Franco regime. EL PAÍS will count them from now on. They are stories like that of Antonio Carpallo, 81, in Seville; Jesús Gutiérrez, 77, in Santander; or Emilio Boyer, 55, in Valencia, who have agreed to tell their memories in the video that accompanies this article. Carpallo was, and still is, a soccer fan. He can recite the Sevilla FC lineup. He also remembers the one from more than six decades ago, when he lived in the Hogar de San Fernando, a Salesian boarding school in Seville. Orphan of father and mother, Carpallo entered there in the fifties. He recounts how one day, at the age of 16, the prefect Rafael Conde “kidnapped” him: “He came to my bed and touched me how and where he wanted. No rush or nervousness. He touched me at the same time that he told me if I wanted to see Sevilla-Valencia. I was a child and an orphan, how was I going to tell him that I didn’t want to watch football? The only answer he could give him was: “Don Rafael, of course I want to go to the game.” “He rewarded me by sending me to see him, which I think I remember ended 4-0,” he shares. He assures that in that boarding school physical violence was the order of the day: “One morning the priest who slept in a corner of the bedroom where I was was attacked me. When he passed me I changed position and he thought I was awake. He started giving me everything he could and more. I don’t know how it didn’t blind me,” he describes. On another occasion, he relates that his brother was locked in a room and three priests beat him up with kicks and punches.

The Salesians have reported that they have already started an investigation of this and the other cases, “regardless of whether they are from years ago.” About the religious that Carpallo points out, the congregation affirms that Conde died in 1976 and that he is gathering more information. “In some of the cases that appear there is very vague reference data, but they will be studied anyway,” explains a spokesman for the Salesians.

The EL PAÍS dossier contains the fundamental data of each case and also the names of ecclesiastical officials who were able to cover up the abuses. In addition, in an annex, this newspaper has included a list of high officials of the Spanish Church suspected of having hidden or silenced cases that have already been published in recent years. Among them are more than twenty cardinals and bishops. The possible cover-up must also be investigated, since it is a crime included in canon law, punishable by dismissal from office if the causes are serious: “Included [in these serious causes] is the negligence of the bishops in the exercise of their office, in particular in relation to cases of sexual abuse committed against minors and vulnerable adults”, reads the motu proprio from Pope Francis Like a love letter.

“I remember his drool on…”

Another story is that of Jesús Gutiérrez, 77 years old. He was born in Santander in a post-war working class family. He was the youngest of four brothers, and the only one who had the opportunity to study beyond what was compulsory. With just turned 12, the city’s Augustinian community hired him to substitute their goalkeepers. In exchange, they offered him high school studies and food. “That was my chance to access culture,” Gutiérrez argues. “The first two years seemed spectacular to me. Some great notes. Until Father Eliseo Bardón [who died last January at the Colegio Nuestra Señora del Buen Consejo in Madrid] became secretary”, he narrates. It was then, in 1959, that his two-year ordeal began: “He called me to help him with office tasks, but it was all a lie. kissed me I remember his drool on me… One day he started to grope me in such a way that I ejaculated. I cried a lot, and he offered to pay me.”

Gutierrez said nothing to anyone. Not even the director of the community, the late father Javier Gorrochategui Múgica, because he also accuses him of having abused him: “He groped me, but he himself realized what he was trying to do, apologized and stopped. However, this action closed the door for me to tell him what was happening to me with Father Eliseo, because if he also had those deviations, that complaint was highly unlikely to prosper. What he did was leave the community, once he finished elementary school. “I swallowed it all by myself. Fortunately, he had a very strong and orderly mind. If not, who knows ”, he concludes, proud of himself.

The decade of the seventies is the one that collects the most cases. Emilio Boyer, 55, also denounces abuses in that decade in the Augustinians of Valencia, both physical and sexual. He accuses Brother Balbino, a religious of the order’s college, now deceased. “I was nine years old and he was leading me down the path of bitterness,” laments Boyer. He says that he beat him, punished him and suspended him. “One day, he and I were in a classroom by ourselves and the guy took off his underpants. I was nine years old, but I knew something strange was going on. ‘Oh, Emilio, if you wanted you could get better grades…’, he told me. Total, that hugs me, with all the tripe there. He had closed the classroom. I started running and he was chasing me. If he had slapped me, he would have ended up giving her fellatio and whatever. He scared me so much that he would hit me… But it didn’t happen from there. He opened the door and let me out.” “After that episode she kept hitting me. It was the worst year of my life”, emphasizes Boyer. EL PAÍS has verified that he is not the only one: he has found another victim and two more witnesses who recount similar memories of Fray Balbino, in the seventies and eighties.

The Augustinians, consulted on these two cases in Santander and Valencia, condemn the abuses and reply that they were not aware of any of them. They’re going to investigate him and go through his files. “Once the judicial process is over, there is always a request for forgiveness from the victims, a removal of the religious from all pastoral activity and the offer of help to the victims in whatever they may need,” they explain.

The report delivered to the Vatican is the result of a long work that this newspaper began in October 2018, with the beginning of an investigation of the abuses in the Spanish Church. More than 600 people have written to the complaint email that he opened then, telling their stories. Listening to them, attending to each one, trying to publish each case, has been a huge task. Behind each message is a person with a painful account of events that happened decades ago and, often, had never been told to anyone before. Telling those memories of a broken childhood is the first consolation, but knowing the truth is her greatest desire. After years searching the internet for the person who abused them, and seeing that he is still in a school, or on a children’s sports team, or even receiving tributes. And in fact, they often feel guilty for not having spoken, for not having had the courage to tell. But it is almost always prescribed, and when they go to church they report that the usual thing is to receive a new humiliation, and rejection. To try to change something, they have written to EL PAÍS.

If you know of any case of sexual abuse that has not seen the light of day, write to us with your complaint at abuse@elpais.es