(CANADA)

CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) [Toronto, Canada]

March 30, 2022

By April Hudson

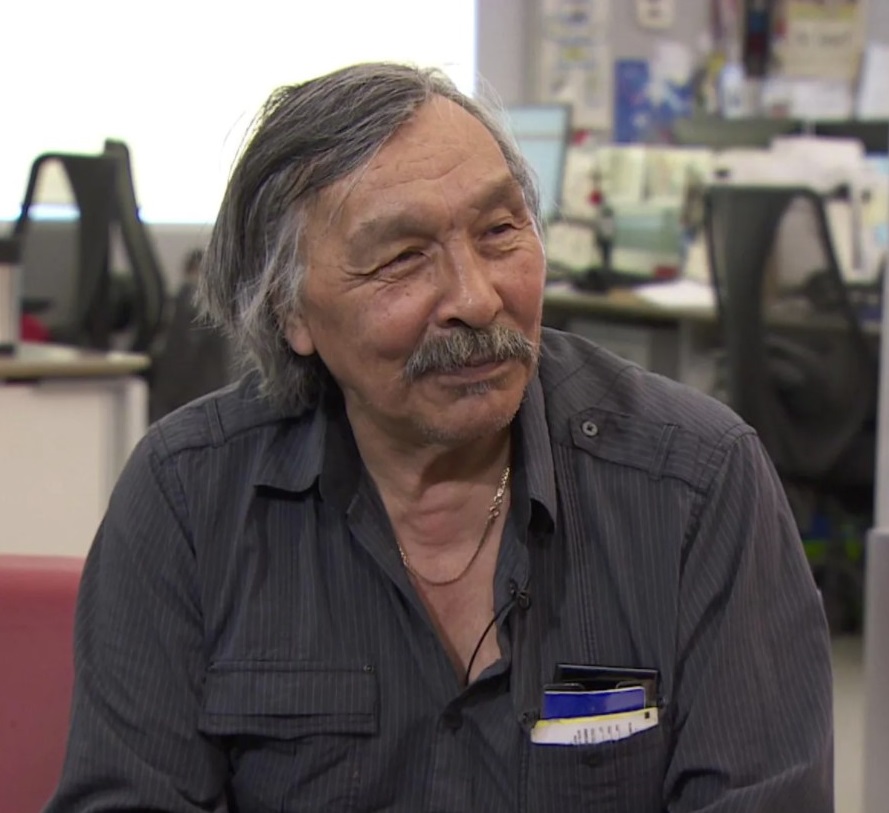

[Photo above: Piita Irniq was 11 years old when he was put on a boat from Naujaat, Nunavut, to Chesterfield Inlet, where he was forced to go to Turquetil Hall Residential School. (Jean Delisle / Radio-Canada)]

Charges should never have been stayed in the first place, says Jack Anawak

Two Nunavut advocates who have devoted decades to shining a light on the atrocities that happened at the residential school in Chesterfield Inlet say they’re glad to see new charges laid against an Oblate priest accused of sexually abusing Nunavut children.

This time, say Jack Anawak and Piita Irniq, they hope the federal government will follow through on making Father Johannes Rivoire face the music.

“Let’s make sure it happens for real this time around,” said Irniq.

Rivoire worked in many Nunavut communities in the 1960s and 1970s, but returned to France in the 1990s. He was charged with sexually assaulting children in Nunavut, but those charges were stayed in 2017.

Former Nunavut MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq drew attention to the case in a news conference in Ottawa last summer, followed by a march for “truth and justice” on the streets of Ottawa.

“Instead of facing justice for his crimes, Rivoire is living a luxurious retirement in a home for priests … and the federal institution is doing nothing about it,” Qaqqaq said at the time.

Nunavut RCMP confirmed this week that Johannes Rivoire faces a new Canada-wide warrant for his arrest. They said they laid more sexual assault charges against Rivoire on Feb. 23, after investigating a complaint in September from someone who said they were abused 47 years ago. They also said no decision had been made about an extradition order, which would be handled by the Public Prosecution Service of Canada.

Anawak said the original charges should never have been stayed.

“They should have kept going until the whole thing was addressed, because those people that he committed abuses on are still feeling the impacts very, very much in life,” he said.

‘We speak the truth’

Irniq, Anawak and their friend, the late Marius Tungilik, were some of the first to speak out about the abuse they suffered at Turquetil Hall in Chesterfield Inlet. They eventually helped to write the apology Roman Catholic Bishop Renald Rouleau delivered in 1996 for what happened at that school.

But neither Irniq nor Anawak are part of the delegation of Indigenous representatives currently in Rome to ask Pope Francis to come to Canada to apologize for the Catholic church’s role in residential schools.

“We went forward with — despite a fair bit of opposition — addressing the rape, physical abuse, emotional abuse, attempted assimilation [in Chesterfield Inlet]. And when we did that, it started the whole process across Canada,” Anawak explained.

“It was … a disappointment to not even be asked for advice on what to say to the Pope during the visit to the Vatican.”

Delegates representing the Assembly of First Nations, the Métis National Council and Inuit are meeting with the Pope in Rome — a visit that has been months in the making. The delegations include elders, youth, support workers, knowledge keepers and residential school survivors, and came about in collaboration with the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Irniq said their exclusion from the delegation process makes him think the church is still in control. He still has high hopes for what the delegation will say on behalf of survivors, though — and for what impact a formal, sincere papal apology within Canada will have.

“I still have hope that they will talk about the traumatization of people, traumatization of survivors. Because being kidnapped right in front of my parents by a Roman Catholic priest in August of 1958, to be taken to Chesterfield Inlet to go to residential school at the age of 11 — that was traumatizing. I was extremely traumatized and I still feel it today,” he said.

“This is not just Indigenous history. This is a Canadian history; this is a Vatican history; this is a Pope history. So it’s important that we work toward healing and reconciliation of our people.”

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools or by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419

With files from Cindy Alorut