VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

National Catholic Reporter [Kansas City MO]

July 1, 2022

By Jason Berry

Pope Pius XII was a slender, ascetic pope who dined alone most nights in the Apostolic Palace, attended by nuns, a pet canary at hand; he then spent hours writing statements and speeches during the long darkness of World War II.

Pius’ words had repercussions he probably never imagined, a language so scripted as not to offend Adolf Hitler and Italy’s fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in the grisly buildup to World War II. The pope made no great outcry as Polish Jews were slaughtered in 1939 and Polish priests went to prison. In 1941, when Hitler invaded Russia, the pope singled out “the great courage shown in defending the bases of Christian civilization and confident hope in their triumph.”

And yet Pius knew the rotten underbelly. When a Roman military chaplain briefed him on Germans dynamiting synagogues in Ukraine and horrific Nazi massacres of Jews and Catholics, the priest recalled: “I saw him cry like a child and pray like a saint.”

Like a saint?

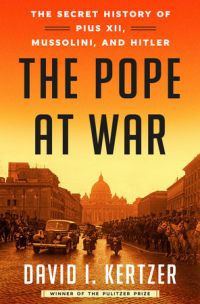

The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler cites many examples of what Pope Pius XII knew and the staggering contrast in his statements — and silence. He voiced no protest in Rome “while more than a thousand of the city’s Jews were rounded up on October 16, 1943, and spent the next two days near the Apostolic Palace waiting to be taken to their deaths at Auschwitz,” as David Kertzer writes in his new book.

As Allied bombs and troops drove the Nazi and fascist forces out of Rome, Pius worried about Soviet Russia imposing godless communism, sweeping away the shards of Christian Europe — his greatest fear in the years he censored the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, aligning the papacy with the fascist march to power. After the war, he began appreciating the real victors.

Accustomed to cheering Italians at St. Peter’s Square or crowded audiences in elegant Vatican reception halls, Pius was heartened by U.S. soldiers and officials packed into Sala Regia outside the Sistine Chapel, stopping often “to speak with the men within reach and offer them his ring to kiss,” writes Kertzer. The pope confided to a U.S. general his unease at their silence, so unlike the Italians’ lively clamor. Americans preferred “a more reverential attitude,” the general explained. “Applause and shouts would have seemed disrespectful.”

Irony shrouds this late scene in the book. As Pius XII, Eugenio Pacelli became a revered post-war figure, praised by Albert Einstein and Golda Meir. Pius today is an increasingly controversial candidate for sainthood as historians have unearthed documents on his refusal to denounce the spread of tyranny and genocide. The pope’s silence was an obsession raised in diplomats’ cables, intelligence reports, memoirs and other documents cited by Kertzer, a Brown University professor, in recurrent references to secret files, released by the Vatican in 2020.

621 pages; Penguin Random House, $37.50

The Pope at War is highly readable, a character-driven history well-paced with textured personalities, and a wealth of granular detail balanced by Kertzer’s even tone, never shrill. As the evidence mounts, one shock after another, he rarely editorializes — the facts are numbingly powerful.

Mussolini forged a cult of personality as Il Duce, “the leader” — a rugged, virile figure whose powerful speeches enthralled the masses, promoting nationalism as Italy’s force of destiny. He gained power by criminal tactics: Fascist thugs murdered union officials, Catholic politicians and editors of independent newspapers, grinding democracy down. Mussolini mesmerized Hitler. The Nazi dictator envied the militant charisma of a man at ease with power.

In August 1939, as Hitler prepared to invade Poland, Mussolini told his mistress, Clara Petacci, it was “a serious mistake.” He thought Hitler delusional. Petacci’s diary rejoices after she and Il Duce make “savage love … I cry for joy.” Then Mussolini gets the call that war will erupt. He broods, “The poor, poor Poles” — he knows they stand no chance; France and England won’t intervene.

Il Duce wanted no part of war in Europe; he doubted Italian troops were well-disciplined enough. Hitler meanwhile had a back channel to the pope. Pius held secret Vatican meetings with a minor German prince. Hitler had violated a concordat with the Vatican that the pope, as Cardinal Pacelli, had negotiated with him in the 1930s as the papal nuncio in Germany. With the Third Reich turning the screws on the church, Pius wanted a restoration of education in Catholic schools.

Citing a Vatican transcript of the meeting, Kertzer quotes the pope, telling Hitler’s secret emissary: “We love Germany. We are pleased if Germany is great and powerful. And we do not oppose any particular form of government, if only Catholics can live in accordance with their religion.” His counterpart raised “a sore point.” Hundreds of priests had been charged with sexual crimes, including the abuse of children. “Such errors happen everywhere,” replied the pope. “Some remain secret, others are exploited. Whenever we are told of such cases we intervene immediately. And severely. If there is mutual good will, we can set such matters straight.”

A year earlier, Kertzer reports, the pope ordered Austrian church officials to destroy files on clerics accused of sex abuse. The author continues:

“In many ways the Nazi regime was anathema to the pope and to virtually all those around him in the Vatican,” writes Kertzer. Hitler envisioned Nazism as a pagan creed of the state. To maintain Vatican influence in Italy, Pius made unseemly compromises with Mussolini, causing priests and bishops to voice support for Il Duce. Pius saw Mussolini as a hedge with Hitler. “One of the Duce’s favorite boasts in speaking with Hitler and the Nazi leadership was of all the benefits he enjoyed by keeping the pope happy,” notes Kertzer.

As the war ended, Hitler married his mistress, Eva Braun, in a fortified bunker, after which they died by suicide. Mussolini and Petacci were captured near Lake Como, shot dead by partisans, their bodies hung upside down as a spectacle to Italians furious over the war.

Pius XII’s post-war halo as a statesman for peace served the aims of Harry Truman, Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle in rebuilding a democratic Europe. In 1948, the CIA worked overtime in Italy as America poured millions into the national elections to defeat the Communist Party and cement power for the Christian Democrats. Much of the money to that end flowed through the coffers of the institution that became the Vatican Bank.

“Vatican City was never violated, and amid the ashes of Italy’s Fascist regime the church came out of the war with all the privileges it had won under Fascism intact,” concludes Kertzer. “However, as a moral leader, Pius XII must be judged a failure.”

Jason Berry

Jason Berry is a longtime NCR contributor who has written three books on the abuse crisis in the Catholic Church. His website is www.JasonBerryAuthor.com.