BUFFALO (NY)

Buffalo News [Buffalo NY]

February 25, 2023

By Sean Kirst

[Photo above: Jonpaul Okal in a ski pass from the late 1970s, roughly the time in which he was abused by then-Rev. Norbert Orsolits. Family photo.]

Jonpaul Okal, raised in Springville, lives with his wife and children in Wisconsin. Five years ago this week, Okal was working at his laptop on a winter’s morning when he received an email from his mother, in Florida. He opened it, assuming it was something routine.

Instead, it contained a link to an article from The Buffalo News and a three-word message:

“Remember this guy?”

Norbert Orsolits, a retired priest from the Diocese of Buffalo who died in 2021, had just admitted to abusing “probably dozens” of Western New York boys during many years at regional schools and parishes. Orsolits publicly described that abuse as somehow consensual, and insisted that in some cases children brought it upon themselves.

It is hard for Okal to describe what those words opened up. He is a survivor. When he was 9, Orsolits – whose family cabin was not far from the Okal home – apparently spotted the child playing outside. Orsolits was soon stopping by, on the pretense of forging a neighborly bond.

He paid particular attention to young Jonpaul. An uneasy Okal began noticing how the priest had a way of pushing up against him, of violating the child’s space.

On an Easter Sunday, after saying Mass for the Okal family in their home, Orsolits followed the boy into the basement and sexually assaulted him. Okal later told his stunned parents. While they banned the priest from their house, they did not go to the police because the distraught child feared the taunting he might endure at school.

Long after he became a father himself, Okal tried to shut away the pain.

That finally changed when Michael Whalen, of South Buffalo, stood outside the diocesan offices in February 2018 and said that as a child, he was abused by Orsolits. Hours later, when interviewed by Jay Tokasz of The Buffalo News, the retired priest confirmed he had molested dozens of children.

“I’m grateful to that guy,” Okal said of Whalen, an emotion shared five years later by every survivor I spoke with in the same week as Ash Wednesday. “It takes a lot of courage to have the guts to say it happened, and to talk about it.”

The diocese, rocked by the admission, finally released a list of priests credibly accused of abuse. Church officials began a “reconciliation and compensation program” in Buffalo to provide settlements for some survivors – but only if they reported abuse to the diocese before the Orsolits revelations, or within a tight window afterward.

Okal, now 53, was told he was too late. Instead, he filed a lawsuit under the new state Child Victims Act, an avenue leading to accusations against 230 Western New York priests – and a process now frozen by diocesan bankruptcy proceedings.

Whalen’s statement swept away years of bureaucratic stonewalling about devastating acts. What makes Okal furious is the knowledge that for generations the diocese buried felony criminal behavior inflicted against vulnerable families, that it allowed “bad dudes to be shuffled off to a new parish, and a new menu of kids, every couple of years.”

No high Western New York administrator of that era was ever held publicly responsible by the church. Children who suffered life-changing assaults grew into adults who believed there would be no reckoning.

The great gift provided by Whalen, Okal said, “was that, hopefully, there’ll be a variant of closure after walling off part of my life.”

Barbara Knight, 65, who struggled with anxiety after her own ordeal, was already discussing her wounds in therapy when Whalen spoke out. Knight said she was abused by Rev. John Doyle when she was a sixth grader in Orchard Park, and then spent decades trying to forget the trauma.

After the Orsolits admissions, she contacted the diocese. Doyle’s name, at the time, was kept off the initial list of abusers – apparently because there was only one accusation. Five years later, he is named as an abuser in three separate CVA lawsuits. To Knight, that provides some vindication.

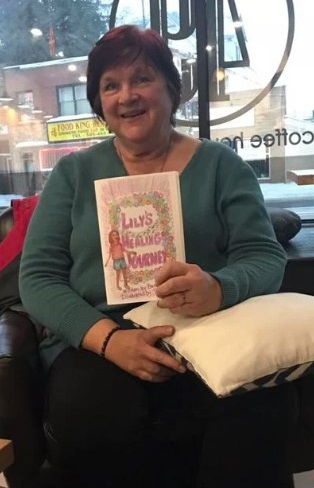

Like Okal, Knight – a journalist and a retired educator – is waiting to see how the bankruptcy proceedings affect her lawsuit. But she found ways of reaching what she calls “my peace.” She describes herself as a person of deep faith, though no longer as a Catholic, and she is grateful for the benefits of therapy.

All of it inspired her to write a children’s book called “Lily’s Healing Journey” – the story of a happy child who endures searing heartbreak, then moves toward healing – that she hopes causes girls and boys “to realize that whatever they’re going through, they don’t have to go through it alone.”

Asked if she had any particular moment of affirmation, she recalled when Bishop Michael Fisher, appointed in 2020, apologized to a group of survivors in a small meeting. What mattered most, she said, “was when he said he believed what we were telling him.”

It was another event that might never have happened without Whalen’s decision to speak publicly, five years earlier.

Denis Riley, now of Florida, was one of the earliest Western New York survivors demanding justice. Riley approached the diocese in 1999 to report he had been abused as a child by Monsignor Edward Walker at St. Joseph’s parish in Fredonia. Administrators vehemently denied it, Riley said, until a second accuser came forward. Even then, they said nothing publicly.

For years, Riley called for the diocese to release all records on Walker, who died in 2002. Riley believes that would prove that high-ranking officials knew of accusations against the monsignor, yet responded by simply shifting him around. Riley, now working on an essay describing the damage Walker caused, puts it bluntly:

“The guy was a monster,” he said of Walker, named in several CVA lawsuits. After Whalen’s accusations shook the diocese, Riley agreed to a settlement within the reconciliation process – and finally saw Walker openly identified as a perpetrator on a list released by the diocese.

Riley, retired at 75 from commercial lending, said the diocese still faces a moral imperative. He joins many survivors in saying true recovery cannot happen without full disclosure of records detailing the times when priests accused of abuse were moved to new schools or parishes.

“One of the things that cannot be overemphasized: It’s always about the money,” said Riley, regarding the long absence of these revelations. He remains a practicing Catholic, based on this reasoning: Any priests who wounded children were the ones betraying the faith.

As for Michael Whalen, his voice cracked and he wept when I told him how these survivors say his courage became the history-changing push that finally overwhelmed diocesan secrecy, going back generations.

“It just means a lot to me to know that when I stood on that corner and said what I said, it was the right thing to do,” Whalen said, “and that my children and grandchildren will always know it.”

In that moment, Whalen “did a great job of holding up a lantern for all of us,” said Michael Eames, a fellow survivor.

Eames, 63, was among dozens of youths targeted by Rev. Donald Becker, publicly accused of abuse in 30 CVA cases – the most of any priest in the diocese. The aftermath caused longtime chaos for Eames, who hid the reason for his suffering even from his worried parents.

He had already joined the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests – and was trying to sort things out in diocese-provided counseling – when Whalen came forward.

The avalanche of subsequent accounts, Eames said, offered survivors long-awaited affirmation: “Everyone could kind of see what happened, and now our story was believed by the general public.”

Becker attacked Eames after giving the 14-year-old from Hamburg beer and whiskey at a rural cabin. A year ago this month, Becker died without ever admitting to dozens of acts of child sexual abuse described in court papers or public statements, but Eames looks at it this way:

“When he tried to cross the Pearly Gates, God was waiting for him – and then, so was my father.”

Sean Kirst is a columnist with The Buffalo News. Email him at skirst@buffnews.com.

Born in Dunkirk, a son, grandson and great-grandson of Buffalonians, I’ve been an Upstate journalist for more than 48 years. As a kid, I learned quiet lives are often monumental. I still try to honor that simple lesson, as a columnist.