VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

Patheos [Englewood CO]

July 10, 2023

By Gabriel Blanchard

[In the Patheos blog Mudblood Catholic]

The Image of Gog

The Vatican reached a new low the other day. (Well, a new low to my knowledge.) I speak of a recent pronouncement made on the subject of Slovenian priest Fr. Marko Rupnik. You may have heard of him. In addition to being a Jesuit priest and author of several books, he is also a liturgical artist of considerable repute, whose mosaics grace the shrines of Our Lady at Fátima and Lourdes as well as the Apostolic Palace in Rome, and a psychological abuser and rapist. Wait, sorry, that was careless of me: Fr. Rupnik is a former Jesuit; he was expelled from the Society of Jesus for disobedience about a month ago.

If that seems like a weird way to arrange and emphasize that information, I’m going to guess that you’re not on the Dicastery for Communication; maybe check and see if they have any job openings, because it sounds like maybe they need a hand. We’ll be circling back to this.

Fr. Rupnik abused several nuns, in a community he helped found, for decades. He also tried to absolve an accomplice—an ecclesiastical crime of the highest order,1 for which he was briefly (!?) excommunicated. I’m given to understand that he actually involved his artwork in the abuse; I’m not clear whether this merely means he used his international esteem as an artist to pressure his victims, or if something even creepier than that was going on.

The Sabbath Was Made for Sin

One of Rupnik’s mosaics had been slated to appear on the cover of a collection of the Vatican’s stamps2; obviously, it was immediately left right there. The same is true of his works in many buildings—churches, mostly—around the world. As far as I can tell, while the idea of removing them has been discussed for months by some individual bishops, none have committed to doing anything, let alone done anything in fact.

As anyone but a scholar or bureaucrat could have predicted, this makes some people uncomfortable.

Now, the Dicastery for Communication has clarified things since. Specifically, they explained that Fr. Rupnik’s art must be separated from the personal conduct of the man who made it. Accordingly, they say, nothing prevents it from continuing to be used in any capacity.

I hope my readers won’t be insulted by my explaining why this is bad actually, since grown men who’ve been working in professional ministry for decades apparently fail to grasp it.

Death of the Iconographer

To explain, let’s move from abusive Slovenian priests to French literary criticism for a moment. “Death of the author” is an important school of criticism that’s seen a good deal of discussion lately, at least among fourteen-year-old Twitter communists. The name “death of the author” comes from a 1967 essay of that title, reacting against the tendency to interpret art in light of (or even just as a vehicle for) the biography, views, and intentions of the author.3 The idea is basically that art should be treated as something that exists in its own right, not as just a vehicle for the author’s views, interests, and psychological complexes. Thus, for example, while Joanne Rowling’s transphobia is execrable, we should, on DOTA premises, deem it irrelevant to understanding the Harry Potter series, or even her mystery novel Troubled Blood.4

I’ll admit that I have extremely little patience with DOTA in the first place, for reasons we needn’t linger over.5 So I might be annoyed by the Vatican’s reaction anyway. But to say it now, about this? when tens of thousands of people have been sexually victimized by Catholic priests, and when this priest specifically used his art to further the harm he was doing? This is a level of irresponsibility a Chicago cop from the 1930s would be ashamed of. It borders on sociopathic to say “just separate the art from the artist” when the Church’s public profile on abuse is and, clearly, deserves to be abysmal. They may as well have sent out a letter reading:

A Hypothesized Letter to the Faithful

From the Vatican Dicastery for Communication

To the many Catholics and former Catholics who have been abused by priests, we hope this finds you basically fine.

In frequenting Catholic buildings for any reason at all, you’re likely to see the art of a priest now known to be a rapist. Indeed, you’ll likely see it not just prominently featured by the Church in her literature, but actually used as an element in her worship of God almighty (because that is the function of art in a church). Someone may have told us that seeing things made by a rapist could cause distress for some reason, or even trigger traumatic flashbacks.

Some people feel that using the art of a sexual abuser in such ways, especially when both he and his victims are still alive, implies that we don’t care about the harm he has done. We’d like to take this opportunity (in case what we’re about to say hasn’t been made clear by our last thirty years of excuses, lies, NDAs, and general inaction) to reiterate that we absolutely don’t care. In our capacity as shepherds—upon whom Christ urged a special tenderness for the most vulnerable of his flock, and whom he warned he would judge sternly if we dared neglect them—we’ve decided that doing anything at all about some mosaics sounds like a lot of work? (Besides, if this were important, surely it would be the big donors who were making the complaint. If anything, seeing as you’re statistically unlikely to be a big donor, this really suggests you’re the one who’s not taking the problem seriously.)

Accordingly, if you’ve got PTSD or Big Mad or whatever because you or a loved one were victimized, or just care about the abuse crisis in any substantive way, we’d like to advise you that that’s your problem.

Enter Magog

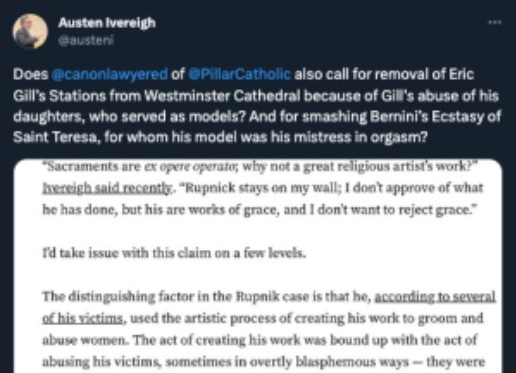

Austen Ivereigh, a British Catholic journalist, also weighed in on the scandal. In fact he’s done so multiple times, both in periodicals and on social media. This screenshot comes from his Twitter, firing back at some criticism he received in The Pillar:

And these are the OP and two replies-to-replies from the thread which drew said criticism:

I don’t know how to write about this man with charity. This outlook is despicable and I have nothing but disgust for it; for that, I do not owe, nor do I make, any apology; but justified anger is one of those feelings that glides into the sin of hating our neighbor extremely easily. Among other things, it has a lot of plausible deniability. So I’ll try to reply only to the ideas he set forth, as if their author were departed to his rest.

Objection the First: Concerning Gill

I hadn’t heard of Eric Gill until some time last year, I think, or maybe the year before. He was a British artist of considerable talent, celebrated as a sculptor and typeface designer: the Gill Sans, Joanna, and Perpetua fonts are all his creations, as are a multitude of sculptures on both religious and secular subjects. He converted to Catholicism in 1913, and shortly thereafter was commissioned to create the stations of the cross that are still in use in Westminster Cathedral.6 He also sexually abused his two eldest daughters, among other behaviors of which I prefer to say nothing.

It baffles and horrifies me that people have been resisting the removal of Gill’s work. Yes, take them down! Obviously! You can just commission new ones! Here’s a concept, bat this around: commission some from anybody not known to be a rapist! This isn’t hard!

“And if they said, ‘rip them all down,’what would you do?” Maybe I’m being unfair, but this tweet makes it sound like victims of sexual abuse are just interfering loudmouths who just like ordering people around. I suppose they should be apologizing to the rest of us for intruding their presence on the rest of the church, getting their devastating personal traumas in the way of art we rather like! “I say ma’am, would you mind not bleeding on the crucifix? It’s terribly gauche behavior; surely you can see that.”

Objection the Second: Concerning Bernini

As for The Ecstasy of St. Teresa being modeled on the sculptor’s mistress in orgasm, a few points are worth making. The least important (and one that, incidentally, also applies to Gill) is simply that he and any victims of his sins are dead. The Lord has put a decisive end to the harm Bernini is personally capable of; this allows separating the art from the artist—if we choose to do so—to proceed with far less danger. Fr. Rupnik is still alive, as are most of his victims if not all. He is even still a priest, albeit no longer a Jesuit.

Secondly, while Bernini shouldn’t have been having relations out of wedlock, that’s just bad old-fashioned sinfulness. It is in no way equivalent to abuse, and it does not send the same message to employ it in art. I wrote about this last year, discussing the disturbingly warped way the story of St. Maria Goretti is usually related by and among Catholics: not only is abuse not the same sin as fornication, they’re not even in the same category of sin. They have a superficial connection, in that both involve sex. But the connection is precisely superficial; abuse is really not about sexual appetite, but power.7 The inability or refusal of numberless Catholics to grasp this was a perpetuating factor in the abuse crisis, and almost certainly continues to be.

And, last but not least: we don’t even know if this claim about Bernini’s work is true. It’s a rumor that has circulated about The Ecstasy of St. Teresa for a long time, but it’s apparently never been confirmed.

A Den of Thieves

So we have two ideas here:

(1) Keeping the art of a living rapist—one who used his art to further his crimes, remember—not only intact, not only displayed in public, but displayed for use in the Church’s corporate worship.

(2) Keeping art made by a centuries-dead man, who may possibly have used inappropriate source material, but wasn’t a rapist, in the same manner and for the same purposes.

Can anyone seriously convince themselves that those two ideas are basically the same? How mentally frivolous do you need to be, how despicable do you need to consider the victims of abuse—whether you say you “sympathize” with them or not!—to not recognize what’s at stake here?

There is a loathsome false equivalence being drawn here. Not just between degrees of sin; not even just between kinds of sin. It is being drawn between two further things: (a) sins for which penance may have been done in any case, and which are in any case not our business, like Bernini’s (always assuming he was guilty of the sin in question in the first place!); and (b) sins for which no clear and public signs of repentance have been published or, as far as I can tell, even asked of the guilty party, and which are our business because that’s how public scandals work! This is one of those cases in which the theological and the vernacular meanings of the word scandal actually coincide—and not only the Holy See, but even laymen, are out here acting as if neither meaning of the word applies!

Sacrament and Sacramental

Ivereigh further posed the question of why, if sacraments work ex opere operato, the work of a great artist can’t do the same. There are several answers to this; the first and foremost is that art isn’t a sacrament. It is, or rather can be, sacramental; that is, a good created thing that can communicate God’s goodness to us, based on subjective factors within ourselves. But that is a crucial distinction which any Catholic of his intellectual stature should know better than to fumble.

Sacraments convey divine grace not based on the personal worthiness of the minister, but because they are divinely instituted signs of God’s covenant, the appointed channels through which he gives us grace. Art isn’t. Art has the meaning the artist gives it, and the meaning the audience gives it, and those things are not worthless. (I here resist the temptation to turn aside to rebut DOTA theory or to offer my own.) But its worth is not divine, because we’re not God. As Simcha Fisher pointed out on Twitter, in reply to Mr. Ivereigh, the Church specifies that this is how the sacraments work because it’s actually pretty weird for things to work this way. Usually, the intent of the originator takes precedence; the sacraments are unusual because they are, on Catholic premises, actual miracles. This is not to be expected of ordinary human craftsmanship. And one of the principal lessons of the prophets is that feigning divine activity, when nothing is happening but human imagination, leads by a short road to monstrosity. Molech was nothing else.

A House of Prayer for All Nations

For the Church to use liturgical art made by sinners is inevitable. But not all sin is abuse, and the Church does not have a systemic problem with all-sin-as-such. For the Church to voluntarily use art made by abusers when she could easily replace it, or could even go without it altogether in a pinch,9 suggests that abuse is not a public scandal and that it is not important for the Church to send a message that abuse is profoundly wrong. But the truth is—and again, this may seem like belaboring the obvious, but only to sane people—ABUSE IS A PUBLIC SCANDAL. THE CHURCH MUST SEND A MESSAGE THAT ABUSE IS PROFOUNDLY WRONG.

To be clear, the Church doesn’t need to preach those things to the world. She needs to preach those things to herself. (Most if not all moral lessons need to be preached first and foremost to oneself rather than other people.) Otherwise, a vast proportion of her clergy, and an uncomfortable proportion even of the laity, are beginning to look as if they are bound for hell; unless they repent.

Thus saith the Lord, the Lord of hosts:

Yet once a little while, and I will shake the heavens and the earth, the sea and the dry land;

and the desire of all nations shall come.

The Lord whom ye seek shall suddenly come to his temple,

e’en the messenger of the covenant, whom ye delight in.

Behold, he shall come, saith the Lord of hosts.

But who may abide the day of his coming?

And who shall stand when he appeareth?

For he is like a refiner’s fire:

and he shall purify the sons of Levi,

that they may offer unto the Lord an offering in righteousness.

Footnotes

1I say tried, because this is an invalid absolution: in other words, it isn’t simply “not allowed,” it’s so severely not-allowed that nothing happens. This fact would undoubtedly be known to Fr. Rupnik, which makes this simulation of a sacrament on top of everything else.

2Yeah, the Vatican makes stamps. TIL.

3To be clear, this tendency was well worth reacting against. Even trained critics blithely read all sorts of things into every work, based on facts, inferences, assumptions, or indeed wild guesses about the creator’s life and thought.

4For those who are unfamiliar, this novel’s villain is a serial killer who disguises himself as a woman in order to sneak into female-only spaces and commit crimes against women. Given that this is a typical “what if” scenario cited to oppose legal and social recognition for trans people, a number of readers felt that this novel reflected its author’s views and anxieties pretty directly.

5The ridiculously short version of why I hate it is that I think the slogan “intent doesn’t matter” is profoundly stupid. Even if we are focusing on impact and right to do so, intent still matters; that’s why we distinguish between murder and manslaughter, for instance.

6Given that Canterbury Cathedral is, ahem, occupied, Westminster (i.e. the bit of London south of the Thames) has housed the leading Catholic bishop in England since 1850.

7This is simplistic, yes. How the desire for power can become sick enough to motivate sexual abuse in the first place is another question. Neither power nor the desire for it are inherently bad; after all, power just means “the ability to do things,” which is good and necessary. It’s likely that sexual frustration often contributes to a warped desire for power; but that’s just because any sense of frustration can do so, if it gets mixed up with our egos and rivalries.

8Ex opere operato is a Latin phrase meaning “from the work that is worked” or “from the work done.” It contrasts with the phrase ex opere operantis, “from the work of the worker.”

9Almost as vile and ridiculous as anything I’ve seen about these scandals is the historically illiterate pretense that getting rid of liturgical art by abusers is “iconoclasm.” This has absolutely nothing to do with the iconoclastic heresy; it attacked representations of God and the saints as such, claiming they violated the first commandment (or, in the most common Protestant numbering, the second). The Church has sometimes done without images: principally in times of severe persecution, when keeping images posed an unnecessary risk. What is necessary to orthodoxy is to confess the legitimacy of images, not to incessantly make and approve new ones without any critical faculty at all.

I would, however, suggest that those who feel their mere personal taste for the art of men like Gill and Fr. Rupnik should override the psychological well-being of the women they raped, are themselves a kind of iconoclast. They apparently think the living image of God in their neighbor is a thing of little consequence, when set beside images in wood, stone, or paint. They thus blithely and sacrilegiously neglect, ignore, and smash the greater ikon in favor of the lesser. C. S. Lewis was right: “Next to the Blessed Sacrament, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.”