LOS ANGELES (CA)

Mountain View Voice [Mountain View CA]

August 31, 2023

By Malea Martin

[Includes timeline.]

Former mayor calls for psychiatrist’s contract to be terminated, wants to know what policies are in place to protect patients

Former Mountain View Mayor Sally Lieber is asking the El Camino Healthcare District to terminate a psychiatrist’s contract and explain what actions it took after the hospital learned in 1988 that the doctor, who has practiced at El Camino Hospital since 1980, was accused of sexual misconduct while a priest in Southern California.

In a July 11 email to the five elected board members of the El Camino Healthcare District, Lieber asked for details on what policy changes, if any, were made as a result of the accusations against Dr. Thomas Havel. The allegations were first brought to light in a 1988 civil suit that accused Havel of repeatedly touching, caressing and attempting intercourse with a girl he was counseling beginning in 1968 when she was 13 and he was a 33-year-old priest at a Pasadena parish.

“It is reasonable to expect that some changes in policy could have been enacted and made apparent to the community in the time since the healthcare district was first publicly made aware of this issue,” Lieber wrote.

Havel, now 85, was never charged with a crime and the civil suit was eventually dismissed in 1992, at a time he was practicing at El Camino Hospital. According to the victim’s attorney, Patricia Marrison, the case was settled out of court, though she said she couldn’t provide further information about the case due to a non-disclosure agreement. This news organization could not independently verify the settlement or its terms.

The hospital just renewed Havel’s contract on July 1 for two years.

According to the contract, which this news organization obtained through a Public Records Act request, Havel currently serves as the associate medical director of the outpatient Adult Mood Program within the Mountain View hospital’s Scrivner Center for Mental Health & Addiction Services.

“I feel like it is time to terminate Dr. Havel’s contract and to start to bring in other people and develop a clean slate,” Lieber said. “As I talked with people who have been impacted by these kinds of situations, I just felt like it’s really time, it’s in the public interest, and it’s just better for the community.”

Havel declined to comment for this story, as did the victim, now almost 70. This news organization is not naming her because she is a victim of an alleged sexual assault.

Lieber wants doctor’s contract terminated, calls for transparency

According to the civil suit, filed in Los Angeles Superior Court in 1988, Havel was 33 and his accuser was 13 when the alleged abuse began. It continued until 1973, including during trips to Southern California after Havel moved to Washington, D.C., to attend Georgetown University School of Medicine in 1971, the suit alleged. The victim was 34 when she sued Havel, after realizing through therapy the affects of the sexual abuse she had experienced, according to the court documents reviewed by this news organization.

In 2007, Havel’s accuser was part of a landmark lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which settled 508 civil cases involving clergy abuse. Plaintiffs received undisclosed shares of a $660 million settlement from the Archdiocese and other Catholic orders.

According to the terms of the settlement, the Archdiocese and other Catholic orders were required to release personnel files of those believed to be perpetrators. Havel’s file was released by the Marianist Order, to which he belonged, in 2013.

San Jose Mercury News coverage of the 1988 civil suit is included in Havel’s released personnel file. According to news archives, El Camino Health was made aware of the allegations against Havel at the time.

In addition to her demand that the hospital terminate Havel’s contract, Lieber told this news organization she worries the health care district may not have established adequate protocols for handling similar cases, including procedures for carefully monitoring patient interactions with a doctor who has been previously accused of improper conduct, after learning about the allegations in 1988.

She urged the board to make public more information on its current policies and to hold a public discussion about the topic.

Lieber, who was elected to the state Board of Equalization last November and announced in April that she would run for Santa Clara County Supervisor Joe Simitian’s seat when he is termed out next year, stated in her email to the district board that she was speaking as “a representative of the communities within the healthcare district.”

Lieber said she’s raising her concerns now because she only recently found out about Havel’s alleged past after Palo Alto resident and victims’ advocate Jamie Barnett posted on social media about it earlier this year. Barnett also wrote letters to El Camino Health and local elected officials about the matter in 2020.

“I saw a post on Facebook in February 2023 from Jamie Barnett saying that when she had been alerted to this in 2020, that she had written to all the local city councils,” Lieber said. “I didn’t recall ever getting notified of it, or I would have taken action then. It turned out that it was before I came back on to city council.”

Hospital reacts

El Camino Healthcare District Board Chair Dr. George Ting said he first heard about the allegations about 30 years ago when he was serving as chief of medical staff at the hospital. Ting said he was not aware of any policy changes put in place at the time as a result of the situation. Ting added that he doesn’t see a need to have a public discussion about it at the board level today, unless it’s brought to the board by staff.

“I’d have to have some confidence in administration’s ability to determine if something does need to be brought up in that way,” Ting said. “Certainly, if there’s something substantial that we need to own up to, there’s no question I would want to bring it up. … If they say that they’ve looked into it, and the existing policies cover it well, and they don’t think we need further investigation, nor change our policy, I take that at face value.”

El Camino Health Communications Director Christopher Brown told this news organization that Havel has been a practicing physician for more than 40 years and is an active member in good standing with El Camino Health’s hospital independent medical staff.

“He is respected among staff, peers and patients,” Brown said in an email. “While allegations from 50 years ago should be taken seriously and thoroughly investigated by the proper law enforcement agencies, these allegations, which allegedly occurred a decade before Dr. Havel joined the El Camino Health medical staff, were never adjudicated in court of law and El Camino Health is not the proper venue for adjudication.”

Brown said the hospital and its independent medical staff – which includes nearly all physicians at the hospital – “have robust policies and procedures in place to ensure that physicians who provide care at El Camino Health are in good standing with the Medical Board of California.” This news organization confirmed through a Public Records Act request that the Medical Board has no record of any disciplinary action taken against Havel’s California medical license.

Brown added that the hospital uses “a robust credentialing process” that includes a criminal background check and ongoing monitoring “to identify potential information about a physician that could jeopardize patient safety,” as well as an internal compliance program to investigate any staff or patient complaints.

If El Camino Health receives information that a current employee has allegations of past criminal behavior against them, Brown said it’s the hospital’s practice to meet with the employee and inform them of the hospital’s knowledge of the allegation. The hospital “put(s) them on notice that there could be actions taken up to termination, should the employee engage in any of the alleged activities while employed at El Camino Health.”

Board Chair Ting added that “the unique circumstances here are that the allegations refer to a time before he became a physician. He didn’t have an MD license, so there would be nothing in any data banks related to a medical investigation.”

Given that there’s no criminal conviction against Havel, Ting said his “personal view is that someone’s innocent until proven otherwise.”

Havel has never been criminally charged for allegations against him. The civil suit against him was initially dismissed in 1989, on the grounds that too much time had elapsed since the alleged abuse occurred. According to court documents, that decision was successfully appealed in 1992 after the court determined that the statute of limitations had not expired, on the basis that the woman had not discovered that she had been abused until many years later. According to Marrison, the woman’s attorney, the case was settled out of court following the appeal.

When it first learned of the lawsuit in November 1988, El Camino Health officials placed Dr. Havel on leave, at his request, while they conducted an investigation into his work at the hospital, according to a hospital spokesperson quoted by the San Jose Mercury News at the time. Within weeks, the hospital announced he had resumed his position as medical director of psychiatry after a review board found his work for the hospital to have been “flawless.” The spokesperson at the time said the investigation looked into Havel’s work as a doctor, not the sexual abuse claims themselves.

In 2014, questions over Havel’s status at El Camino Hospital surfaced again when Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), a victims’ advocacy group, connected his name from the list of “credibly accused” abusers made public by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles with his position at the hospital. SNAP members petitioned El Camino to remove him from his position, but according to the group, El Camino Health did not respond.

Yannina Diaz, an Archdiocese spokesperson, told this news organization that Havel was included in the Archdiocese’s 2004 Report to the People of God, which acknowledged the widespread child sex abuse within the church.

Diaz said that Havel was included on the list because “the Archdiocese received a report in 2002 by an adult alleging sexual misconduct by Havel when she was a minor in 1968 to 1973.” This accuser is the woman whose civil case against the Archdiocese was settled as part of the 2007 global settlement.

Diaz said all clergy who were part of the settlement were added to the list, regardless of whether the Archdiocese had enough information to independently investigate them. The list was reviewed by the chair of the Archdiocese’s Clergy Misconduct Oversight Board prior to release.

“The Archdiocese had little information on Havel because he was on leave in medical school for most of the time he was associated with the Archdiocese, and he left the Archdiocese in 1972, 35 years prior to the global settlement,” Diaz said.

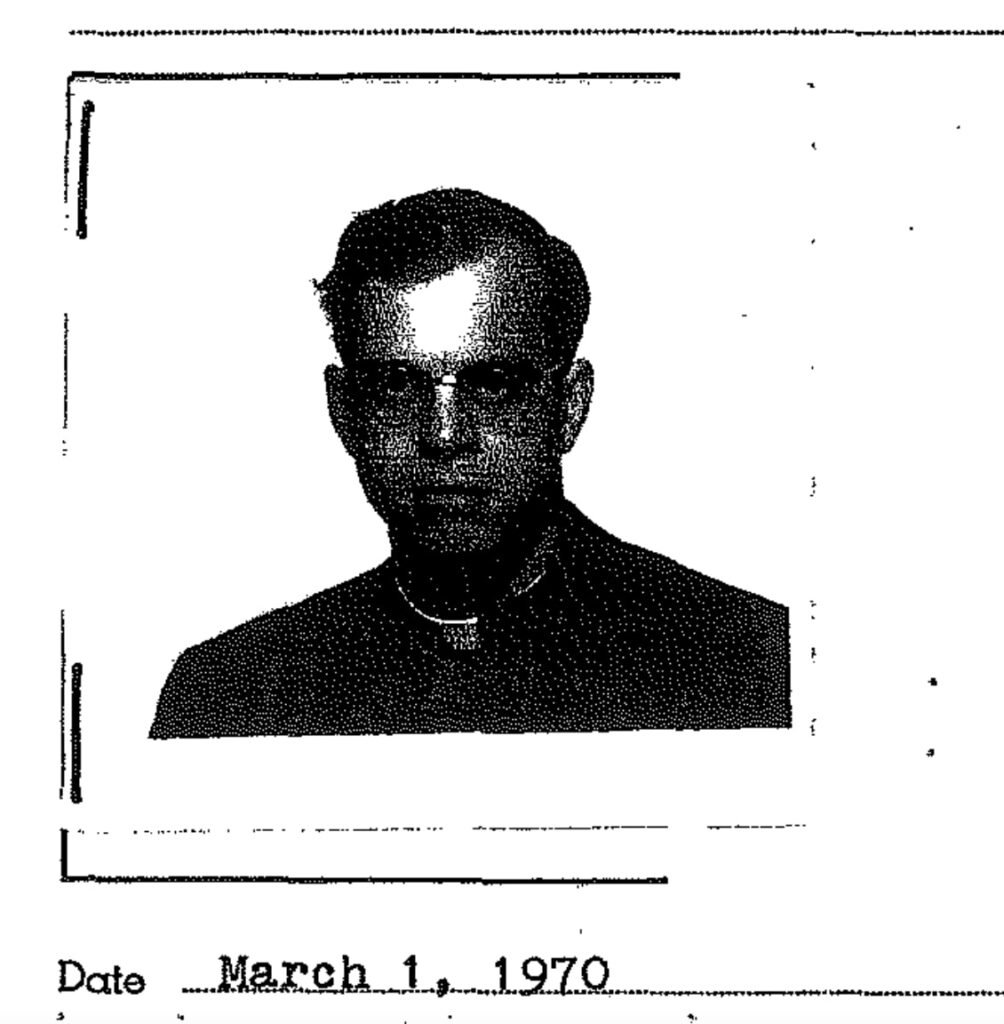

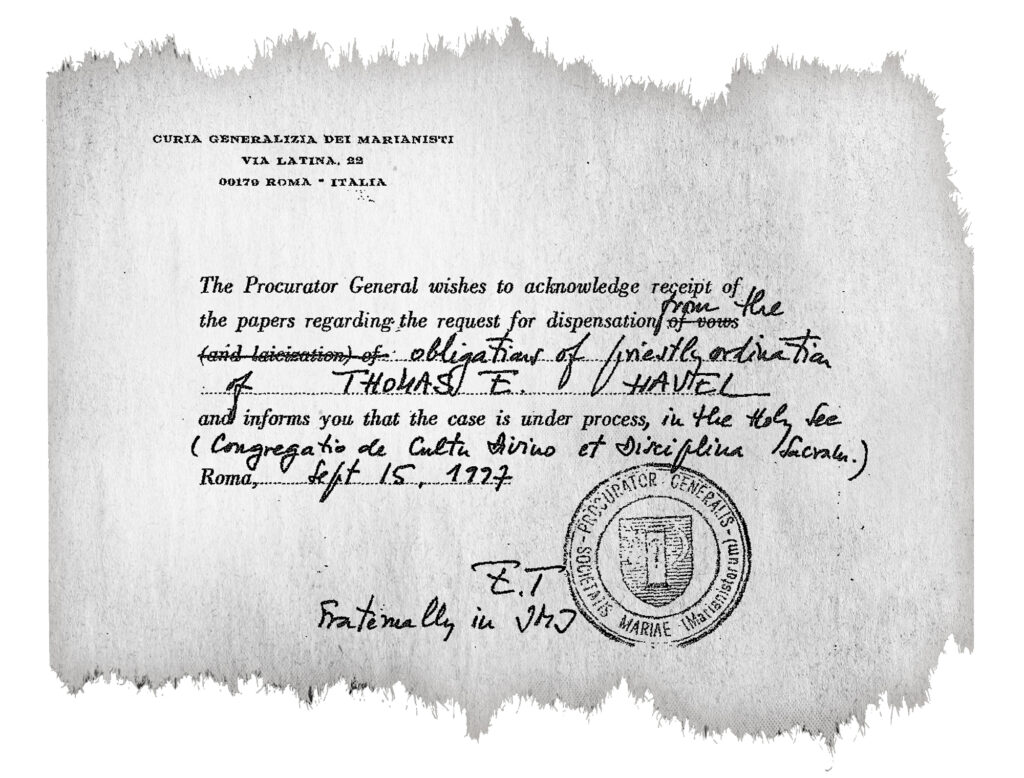

Under the settlement agreement, the Archdiocese and other Catholic orders were required to release the personnel files of all clergy included in the settlement. Havel’s redacted file is 432 pages long and includes letters and documents detailing his time as a priest, his enrollment and graduation from Georgetown Medical School and his eventual laicization – leaving the priesthood – in 1997.

The file contains mostly mundane details about Havel’s life as a priest and medical student: A letter to another member of the church where he ponders whether he should wear his clergy attire to his classes; the cost of his tuition and textbooks at Georgetown; a program from his father’s funeral. It also contains brief references to the lawsuit from the late 1980s, as well as newspaper clippings from the Mercury News’ coverage of the case.

Havel’s contract with El Camino Health

Havel’s current contract with the hospital as the associate medical director of the outpatient Adult Mood Program is capped at just 27 hours a month. The Adult Mood Program provides treatment for people experiencing significant mental health mood symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, according to the El Camino Health website.

Under a second “professional services” contract, which was renewed in 2022 until June 30, 2024, Havel also participates in an on-call rotation with other psychiatrists for emergency consultations, non-emergency requests from hospital staff and performs hospital rounds during daytime weekend shifts in the Behavioral Health Unit.

Between July 2020 and April 2021, Havel’s previous contract shows he was given the added responsibility of serving as the interim Behavioral Health Services chief medical director while the hospital sought a new permanent director. He was limited to 74 additional hours per month to carry out that responsibility, according to the contract.

Lieber said she finds it troubling that Havel was promoted to the interim director position despite the hospital’s knowledge of the allegation against him.

“It just boggles the mind that they would put an individual with that kind of cloud over their record into a situation where they have access and control,” Lieber said. “It’s incomprehensible that there would be nobody else that they can promote into that position.”

According to El Camino Health, Havel was paid $59,540 in 2022, $46,673 of which was for serving as the associate medical director of the Adult Mood Program and the balance for on-call fees. The El Camino Health website states Havel is no longer accepting new patients. This news organization could not determine if he continues to have a private practice outside of his work for the hospital.

Advocates react

Former SNAP president and current volunteer Tim Lennon, who led the 2014 petition calling for Havel to be removed from his position, called the hospital’s decades of inaction against Havel “mind boggling,” but said it’s nothing new for alleged abusers to avoid consequences.

“Institutions – whether it’s the bishops or hospital administrators – seem to want to protect power and prestige at the expense of young people and the vulnerable,” Lennon said.

As a survivor of childhood sexual abuse by a priest himself, Lennon said it’s a practice that’s especially infuriating for him to witness. And according to attorney Raymond Boucher, who led the $660 million settlement lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in 2007, the hospital’s inaction is also a potential legal liability.

“Whether it’s been proven or not proven is really immaterial to the question,” Boucher said. “Once an entity, of any kind, is on notice that somebody may pose a danger involving sexual abuse or sexual harassment or sexual assault towards a minor or an adult, that entity is obligated to take steps to ensure the safety of those individuals.”

Although Havel is 85 and the alleged abuse took place more than 50 years ago, Boucher said a person’s age shouldn’t stop them from being held to account.

“From a public safety standpoint, from a public health standpoint, from a human decency standpoint, it doesn’t matter how long it has been,” Boucher said. “What matters is that there’s sufficient notice and knowledge, and that we don’t forget … so that we remain vigilant in protecting people. Because ultimately, that’s the most important thing, isn’t it?”

Malea Martin covers the city hall beat in Mountain View. Before joining the Mountain View Voice in 2022, she covered local politics and education for New Times San Luis Obispo, a weekly newspaper on the Central Coast of California. 650.223.6516