BALTIMORE (MD)

The Daily Record [Baltimore MD]

October 1, 2023

By Rachel Konieczny & Madeleine O'Neill

For the first time in Maryland, survivors of childhood sexual abuse can now sue perpetrators and the institutions that protected them without concern for how long ago the abuse happened.

Maryland’s Child Victims Act, which eliminated the statute of limitations for civil sexual abuse claims, officially goes into effect Sunday, Oct. 1, though courthouses are closed until Monday.

The victory for survivors was dampened, however, when the Archdiocese of Baltimore filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Friday afternoon. Though the Roman Catholic Archdiocese was expected to face a flood of lawsuits over clergy sexual abuse, the bankruptcy will put all litigation on hold and force survivors to pursue compensation in bankruptcy court, rather than through a lawsuit.

Other survivors, however, will still have the chance to file lawsuits under the CVA. People who were victimized at schools or other institutions not connected to the archdiocese are unaffected by the bankruptcy filing.

Lawmakers passed the CVA earlier this year, days after a damning report by the Maryland Attorney General’s Office revealed decades of clergy sexual abuse and coverups in the archdiocese.

Lawyers told The Daily Record they expect a large number of cases to be filed quickly, though that will surely be affected by the bankruptcy filing.

Several states that passed legislation similar to the CVA in recent years saw the number of lawsuits top 1,000, according to Child USA, a think tank that works to advance child protection laws.

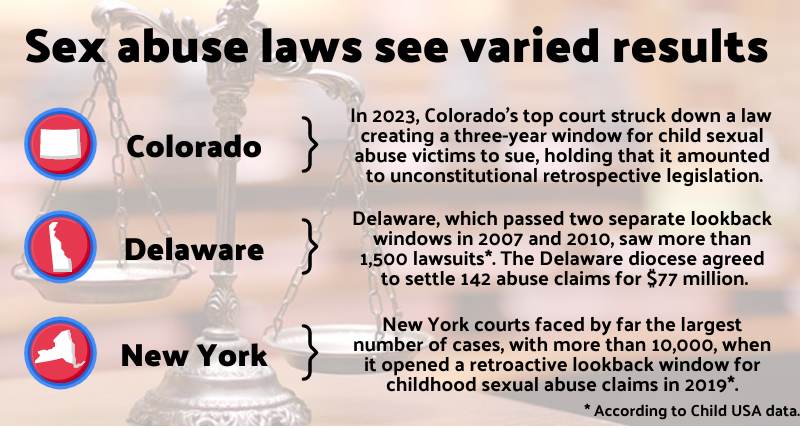

New York courts faced by far the largest number of cases, with more than 10,000, when it opened a retroactive lookback “window” for childhood sexual abuse claims in 2019, according to Child USA’s data. Delaware, which passed two separate lookback windows in 2007 and 2010, saw more than 1,500 lawsuits.

Lawyers in Maryland said they have not received guidance from the Maryland Judiciary on how the influx of cases will be handled here. A spokesperson for the judiciary said the court would not take action until a case has been filed.

Steven J. Kelly, a lawyer with Grant & Eisenhofer P.A. who is known for his work on crime victims’ rights, said he expects there to be more coordination once the lawsuits get underway.

“I think that once cases are filed, parties are represented by lawyers and judges can have conversations with both sides, that’s the time when some efforts will be made to figure out, procedurally, how to get through this,” he said.

Plaintiff’s lawyers are trying to put their best cases first, said Phil Federico, a lawyer with Baird Mandalas Brockstedt & Federico who joined a coalition of law firms representing abuse victims.

That’s because the CVA is expected to face a swift constitutional challenge that will likely end up before the Maryland Supreme Court. The law’s opponents have argued it is unconstitutional to retroactively remove a statute of limitations, and lawmakers accounted for an “interlocutory appeal” in the legislation.

“A case, we don’t know which case, is going to make its way to our Supreme Court for a determination as to the constitutionality of the statute,” Federico said. “We know where the road begins, and we know where the road ends. What we don’t know is how we’re going to get there.”

By starting with the strongest cases — those that allege clear negligence by an institution that should have protected children — plaintiff’s lawyers are hopeful the Supreme Court will be able to get to the constitutionality question quickly and without wading through extraneous issues.

Federico, Kelly and Robert K. Jenner, another Baltimore-area lawyer known for handling abuse cases, gathered for a news conference Friday to announce their first group of cases.

They include claims from two women who say they were groomed and then sexually abused by male faculty members at the private Key School in Annapolis.

They were also set to include lawsuits from two women who say that, as schoolgirls, they were repeatedly raped by A. Joseph Maskell, a now-dead priest who was accused of sexually abusing multiple students at Archbishop Keough High School in Baltimore, but those suits will be barred because of the bankruptcy.

“It’s going to be probably a diverse group of cases to identify a diverse group of plaintiffs and a diverse group of defendants, so that the Maryland Supreme Court can understand that this is not just an Archdiocese of Baltimore issue,” Jenner said of the early cases that could make it to the high court.

“The tragedy of childhood sexual abuse involves a spectrum of people,” he said.

Maryland courts can still move forward with the constitutionality question despite the archdiocese’s bankruptcy; another defendant, such as a school, could be at the center of the case that ultimately makes it to the Maryland Supreme Court.

Maryland’s law has an added wrinkle: In 2017, a “statute of repose,” a little-known legal mechanism that created a hard cutoff for future lawsuits, was added to a bill that extended the statute of limitations for civil child sexual abuse claims to 20 year after the victim turned 18.

The 2023 Child Victims Act ended the statute of limitations entirely, but opponents argued that the statute of repose created a “vested right” that protected institutions from out-of-date lawsuits. Lawmakers who were involved in the 2017 bill have said they were unaware the statute of repose had been added.

Litigation in other states

Still, if other states are any indication, Maryland’s law seems likely to survive a court challenge.

Appellate courts in a number of other states have upheld the constitutionality of legislation like the CVA, a fact that gives advocates hope for Maryland. Information compiled by Child USA shows that courts have ruled in favor of these laws in at least 12 states — and that doesn’t include more recent decisions like one in North Carolina that upheld the 2019 SAFE Child Act.

“Certainly the overwhelming force of appellate opinions is supporting the constitutionality of the statute, but it’s not universal,” Jenner said.

Only a few state courts have ruled against laws like the CVA. The Colorado Supreme Court is one of them.

Colorado’s Child Sexual Abuse Accountability Act of 2021 (SB 21-088) created a three-year window for child sexual abuse victims to sue for misconduct that occurred between 1960 and Jan. 1, 2022. However, in June, the Colorado Supreme Court in Aurora Public Schools v. A.S. held the law amounted to unconstitutional retrospective legislation.

Though not many cases were filed under the Colorado act, some used the law as leverage to see if a case could be settled prior to filing a lawsuit.

Charles Mendez, an attorney at Denver Trial Lawyers who represents sexual abuse victims, said the legal community knew that challenges to the act were coming when the law was being passed in the legislature.

One lawsuit filed prior to the Colorado Supreme Court’s June ruling came in 2022 with the case of Brian Barzee v. Archdiocese of Denver, where Barzee alleged exploitation and sexual abuse by a former priest when in high school. A spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Denver was not available for comment.

Mendez said it’s often difficult for child sexual abuse victims to confront their abuse in terms of acknowledging the wrongful behavior of their perpetrators and then being able to share their experience with others.

“It’s pretty shocking how many years it takes for the average child victim of abuse to come forward,” Mendez said. “It’s entirely unrealistic in practical terms for a child who’s abused to meet most states’ statute of limitations.”

Mendez said that while lawsuits are no longer an option for child sexual abuse victims since the act was struck down, legislators and advocates are working on pursuing other options, such as a constitutional amendment.

Elizabeth Newman, public policy director of the Colorado Coalition Against Sexual Assault, said the act provided many survivors with hope that they had not previously had because their abuse happened so long ago.

“For folks who have been living with the consequences of what happened to them for nearly their entire lives, the opportunity that was presented with Senate Bill 88 was huge and really gave them a chance to tell their story in a way where people will listen to them,” Newman said.

Newman said to have the act overturned is “devastating and heartbreaking.” However, because it had bipartisan support in the Colorado General Assembly, Newman said she expects any new legislation or an amendment to find support once again.

The bankruptcy scenario

In Maryland, the Archdiocese of Baltimore chose Friday to file for bankruptcy, following a common tactic among Catholic diocese facing abuse lawsuits.

“The problem that we’re facing now is that the diocese are opting to file for bankruptcy,” said Irwin Zalkin, a California-based lawyer who specializes in clergy abuse cases. “Their big argument is that with all these cases, and if you pass legislation that eliminates the statute of limitations and exposes us to potential liability forever, from their standpoint they’re saying we need to get the protections that we can get in a bankruptcy that would essentially immunize us from future liability.”

Filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, or reorganization, places all claims against the archdiocese on hold. Instead of taking their lawsuit before a jury and seeking damages that way, survivors will have to file their claims with the bankruptcy court and receive payments out of a designated pool of money from the archdiocese’s assets.

That’s what happened in Delaware, where the Diocese of Wilmington filed for bankruptcy on the eve of a trial in 2009, after the state’s own Child Victims Act took effect.

The Delaware diocese, which did not respond to a request for comment, agreed to settle 142 abuse claims for $77 million in 2011 as part of its bankruptcy proceedings.

Thomas Neuberger, a Delaware attorney with a long history of representing abuse victims, said average settlements for survivors in Delaware came out to about $600,000 — less, he believes, than survivors might have gotten from juries. Even private settlements reached with the church before the bankruptcy were worth more, ranging from about $1.5 to $2 million, he said.

Now, the church is facing even more dire prospects if these cases go to trial, Neuberger said. In the years since Delaware’s law passed, laws like the CVA have gained momentum across the country, and awareness of childhood sexual abuse has continued to rise.

“A lot of water has gone over the dam since then in the public mind,” Neuberger said.