TEHUANTEPEC (MEXICO)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

March 19, 2024

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

[Photo above: The members of the Southern Cross province of the Oblates, 2018. In the circle, Rafael Fleitas López.]

Rafael Fleitas López, a priest accused of sexual abuse in Paraguay, has been received in Mexico by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a Catholic religious order.

Fleitas López could restart his career as a priest in the Mexican town of Magdalena Tequisistlán, despite having been accused of sexual abuse in Paraguay.

Religion and public life: The Oblates would have sent Fleitas López to the Mexican Rougier Center for a three-month therapy to prevent sexual abuse, so the bishop of Tehuantepec, Mexico accepted him.

This is a story about the way in which a Catholic religious order with a global presence, can move with relative ease a Paraguayan priest accused of sexual abuse in his country and send him to Mexico, to a small rural town of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

It is a story that reveals the weakness of Mexican and Paraguayan civil law when dealing with the rights of victims of sexual abuse. It also reveals the disdain with which the Catholic hierarchy in Latin America addresses the sexual abuse crisis, the problem that is destroying it, undermining the trust of its faithful in their priests and bishops.

It is the story of how Juan Rafael Fleitas López, a Paraguayan priest of the order of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who served as such in the parish of Our Lady of the Rosary in General Artigas, Paraguay, is about to resume his duties as priest in the parish of Sait Mary Magdalene Tequisistlán, in the diocese of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, in the Mexican Deep South.

He would not be the main priest there. Some say in the houses of the Oblates in Paraguay that he would be limited in his functions. The limits, however, are not clear, since as far as it has been possible to find out, he would be allowed to celebrate mass and, above all, he would be allowed to hear confessions.

Sadly, one of the settings in which harassment that precedes sexual abuse most frequently occurs in Catholic environments is that of the celebration of the so-called sacrament of reconciliation, more commonly known as confession, which by its very nature allows sexual predators to identify potential victims.

In fact, as the Paraguayan press tells it, it was precisely during the confession of a female that Fleitas López verbally and spiritually abused her, even though she had gone to look for him after her father died in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic.

The verbal and spiritual abuse was expressed in the absurd way in which he forced her to perform three days of prayer before confessing her. Despite this, the victim complied with the unusual requirement, and it was on the third day of prayer that, after forcefully kissing her, he attempted to sexually abuse her.

The victim fainted and although, at that moment, she did not reproach Fleitas López for his behavior, days later he fainted again. It was then that he informed his family and began the process that explains this story.

This is certainly not a nationalist or chauvinist story assuming that only Mexican priests should provide religious services in Mexico. Marcial Maciel is proof of how dangerous Mexican priests can be.

Exchanges and warnings

Any exchange of professionals from any discipline can be very positive. Exchanges of religious personnel between Latin American countries have occurred since before we existed as independent countries of the Spanish Empire and these types of exchanges also occur with European countries, with the United States and Canada and, increasingly, with African countries.

The problem is that these exchanges have served in other times to hide and cover up sexual predators. That was the case when Cardinal Norberto Rivera Carrera, then bishop of Tehuacán, in the Mexican state of Puebla, sent a priest from to Los Angeles, California, where he was received by the then archbishop Cardinal Roger Mahony.

Helping Rivera Carrera hurt Mahony’s career, since the serial sexual abuse perpetrated by Nicolás Aguilar in both Mexico and the United States was part of the multimillion-dollar compensation that the Californian archdiocese is still paying up until today, almost twenty years after the first details of those abuses were known.

Mahony was even forced to and early resignation from his diocese. The paradox that Mahony had to pay with money and with his resignation while Rivera could remain a sitting bishop until he turned 75 when both were guilty of having helped Nicolás Aguilar, cannot be ignored.

What is worse, it can only be explained because the United States justice system is effective in pursuing and punishing sexual abuse. In Mexico, on the other hand, the victims are again and again victimized by both the Catholic hierarchy and the Mexican authorities.

What follows should be a cautionary tale of what could happen if, in the coming days, the diocese of Tehuantepec actually allows the Paraguayan Oblate Juan Rafael Fleitas López to return to exercise the priesthood in Mexico.

That this is the case is due, in large part, to the indisposition of the Catholic Church itself to recognize—40 years after the beginning of the sexual abuse crisis—its own errors.

However, it is also due to the laxity of the existing laws regarding sexual abuse all over Latin America that work for the benefit of clerics or other public figures, such as politicians, businessmen or academics.

It must be admitted: being a sexual predator in Latin America comes cheap. In fact, in more than one country, sexual predators have more chances of being protected than victims; The Catholic Church itself, obsessed with conspiracies against it, prefers to be protected as an institution rather than acting as an institution that protects its flock, the people who give life to the institution.

Said attitude sets the tone for the way in which cases of abuse perpetrated by those who direct or represent other institutions. Protecting institutions instead of victims makes sexual abuse processes especially slow, difficult, and increase the chances of victims to be re-victimized.

Unlike current legislation in the United States and other English-speaking countries, in most Latin American countries it is at the discretion of the bishop or the superior of an order to decide when to report cases of sexual abuse to the authority.

The justice systems of Latin America are alien to any type of haste or urgency when it comes to caring for victims of sexual abuse from the Catholic Church, other churches or forms of organized religion, as demonstrated by Naasón Joaquín García’s case, the Mexican leader of the Church of the Light of the World, the so-called Luz del Mundo Church, who has been tried, like Mahony, in California and not in Mexico, where that religious organization has its main base of operations and most likely the largest number of victims.

From southern Paraguay to southern Mexico

Juan Rafael Fleitas López is a priest who is a member of the so-called Oblates of Mary Immaculate, an order founded in France at the beginning of the 19th century with a presence in Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

I was able to find, after reading several issues of OMI Information, the internal communication bulletin of that religious order, that Fleitas López was born in Concepción, Paraguay, although there is no data regarding his date of birth.

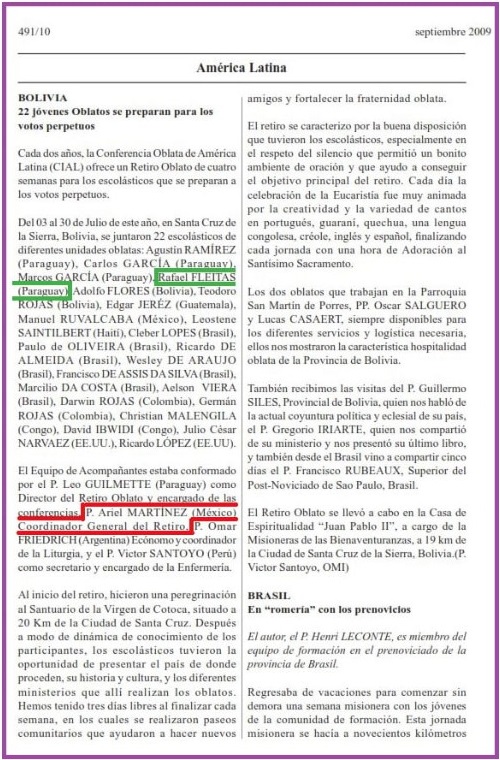

It is possible to infer that he would have entered that order in the first years of this century, perhaps in 2003 or 2004, since the bulletin of September 2009 reports that he was part of the group of scholastics (equivalent to seminarians) who would present or assume their final vows in the then near future.

That bulletin of September 2009 is very important because it confirms that there was a relationship between José Ariel Martínez Morales, the current superior of the Province of Mexico, Guatemala, and Cuba of the Oblates and Fleitas López who, at that time, was already a member of Oblate community in Paraguay, which is now part of the Cruz del Sur Province that integrates Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

It is a fact that they coincided there. It is possible that they have met before and it is also a fact that Ariel Martínez, the current Mexican superior of the Oblates, has played a key role in getting him to come to Mexico.

And indeed, the February 2012 bulletin reports that Fleitas López made his “Perpetual Oblations” on January 18th, 2011, and his, so-called, “Obedience” on July 8th, 2011.

If he followed a similar route to that of other Oblates about whom there is more complete and precise record, he would have been ordained deacon that same year, 2011, and priest or presbyter the following year, 2012, although no information was found about the precise date and place of his ordination.

It would have been a maximum of two years after his training had concluded, so at the time of the attack at the Our Lady of the Rosary parish, he would have between four and up to five years of experience as priest. What was possible to establish is the day on which the anniversary of his ordination is celebrated.

This piece of information appears on the Facebook page of the Province of the Southern Cross of the Oblates, which published the photograph appearing immediately after this paragraph and which gives the date as October 29th.

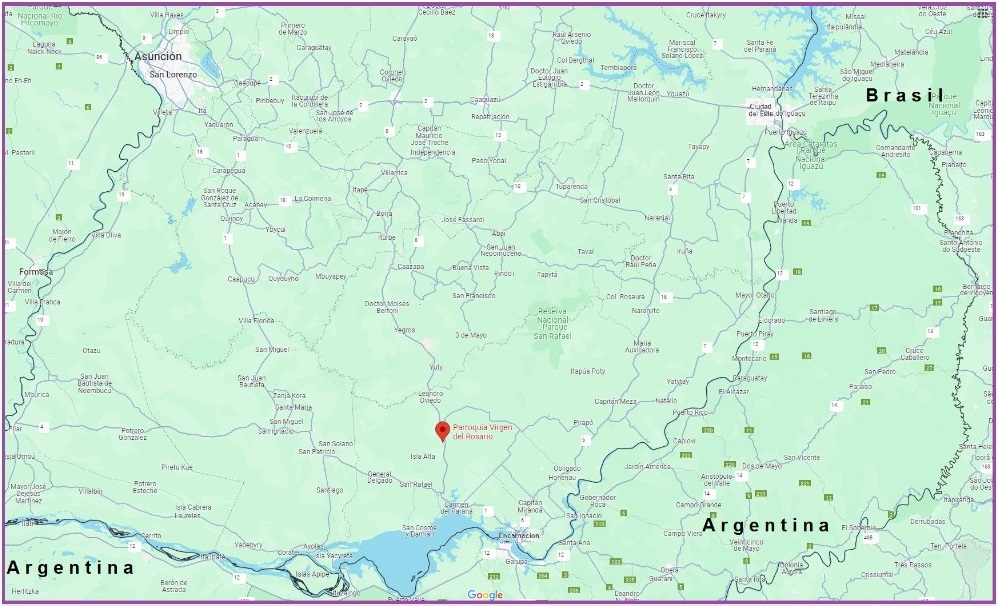

That parish is in Ciudad Artigas, the Paraguayan Deep South, 36 miles or 57 km from Encarnación, the southernmost of the Paraguayan cities, located right on the border with Argentina. Ciudad Artigas is also located 142 miles or 230 kilometers from the national capital, Asunción. You can check its location on Google Maps here.

And although Paraguay remains the Latin American country with the largest share of Catholic population, that could soon change.

In the Oblate order it has not been only Fleitas López who has abused members of its flock.

In fact, a notable difference between the Mexican Oblates and their Paraguayan counterparts is that while the Mexicans maintain several social media accounts, a very well-designed website, in addition to very attractive newsletters that only provide information from the province that includes Mexico, Guatemala and Cuba, those from Paraguay had to close their social networks.

Before Fleitas, in 2006, there was a more scandalous case involving two priests who were already priests when Fleitas was a scholastic or seminarian in that order: Gustavo Ovelar and Francisco Javier Bareiro.

It is not possible to distract the narrative from the Fleitas case. Anyone interested in these other cases of the Paraguayan Oblates can consult some of the press releases that are still available about Ovelar and Bareiro, whose victims waited ten years to denounce their predators, as can be seen in this story from Paraguayan newspaper ABC Color.

And the President too

For other reasons, another member of the Oblates, the German-born priest Heinz Wilhelm Steckling, gained world fame when he was called in 2014 as a firefighter by Pope Francis to take over the diocese of Ciudad del Este, which is located right on one of Paraguay’s borders with Brazil.

That year a scandal broke out in Ciudad del Este when details emerged of the power granted by Bishop Rogelio Ricardo Livieres Plano to the traditionalist priest Carlos Urrutigoity, a native of Argentina who had had to flee the United States when his name emerged in a series of criminal cases ranging from financial and Real Estate fraud to sexual abuse in both New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Catholic magazine Commonweal provided a detailed account of that case on a series aptly titled The curious case of Carlos Urrutigoity (available here at Bishop Accountability).

Livieres Plano was a member of Opus Dei and of a well-off family with roots in both Argentina and Paraguay, who gave Urrutigoity almost unlimited power. Moreover, despite his experience in the United States, Urrutigoity unleashed a despotic rule over Ciudad del Este’s curia and seminary.

Livieres Plano made Urrutigoity his right hand. He made him his vicar, gave him power to dismiss other priests and put him in charge of the diocese’s seminary which became a “hunting preserve” of sorts.

And if one digs a little deeper into Paraguayan public life, there is the case of the bishop who became President, Fernando Armindo Lugo Méndez, who was a member of the so-called order of the Society of the Divine Word. He was appointed by John Paul II in 1994 the bishop of the diocese of San Pedro, despite that there was evidence that he failed to comply with the precept of chastity.

So far, no formal accusations of sexual abuse have arisen against him, but at least three women have demanded payment of child support for the children he fathered with them while he was a priest and later a bishop.

It is also worth mentioning that the database of Bishop Accountability, a global non-governmental organization that documents cases of abuse at the hands of Catholic clergy, has information on the case of Luis Sabarre, an Oblate originally from the Philippines, who allegedly abused his flock in Argentina, where he was denounced in 2010 at the archbishopric of Mendoza.

The accusation was unsuccessful both in canonical and civil tracks. A summary of his case can be found here.

It is also noteworthy that the very fact that this story is focused on the Oblates contains a paradox of sorts. Until Friday March 15th, when changes were reported in the entity known by its Latin name as Tutela Minorum, that is, the one responsible for ensuring the protection of minors, the secretary of that unit of the Vatican Curia was the British-born Oblate priest Andrew Small.

A previous story published only in Spanish at Los Angeles Press was dedicated to Small’s tenure at Tutela, because of the opacity with which funds were transferred from other entities of the Catholic Church for the operation of Tutela. That story in Spanish is linked immediately after this paragraph.

One would assume that—given Small’s status as an Oblate—that order would be better prepared to respond more efficiently to sexual abuse allegations, with a better understanding of what Pope Francis has called the “spirituality of reparation.” Sadly, as this story proves, that is not the case.

It is not possible to address the detail of what is happening in the Oblates, but the numbers that they themselves publish on their Internet sites and bulletins speak of a crisis.

Founded in 1816, in France, it experienced its peak in the sixties of the last century when it had 5,441 priests and 7,875 non-ordained brothers associated with the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. At that time, they occupied a total of 1,604 “houses” or establishments, which still grew to 1,700 in 1971.

Of those glory days there are nothing but memories. The contingents have been reduced, according to the data reported to Rome, to 2,364 priests, 3,694 non-ordained religious, distributed in only 633 houses or establishments, as can be seen in the graph that appears below.

The crisis of the Oblates on a global scale can be summarized in the fact that they have lost, in just over ten years (2011-2022), 74 priests, which represents 2.55 percent of the just under 2,900 priests they have trained in the last ten years, not counting those who die.

There are terrible years like 2019 and 2012, in which they lost 13 and 12 priests, respectively. In total, in the period from 2011 to 2022, they have expelled 46 priests, two brothers, that is, religious who chose not to pursue the studies to become priests, two scholastics, which is what religious orders call their seminarians, and five members of that order whose degree or type of membership in the organization could not be determined.

They have lost 479 scholastics or seminarians who chose not to renew their vows and only 43 formally asked to be excused from those temporary vows. The worst years on this issue were 2014 and 2013, when 99 and 80 aspiring Oblates, respectively, decided to let their temporary vows expire, without renewing them.

As for those who chose to request dispensation from their temporary vows as a scholastic or seminarian, the two worst years were 2012 and 2013, when nine seminarians in each of those two years asked to be excused from their temporary vows.

To the priests who were expelled, presumably for some violation of the rules or regulations of the order or the Catholic Church, another 33 must be added. Those asked to be incorporated or incardinated, according to the jargon of canon law, to another diocese or join another religious order.

It is true that other orders or congregations have faced similar crises. What these orders and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church would have to ask themselves is what role the crisis of sexual abuse plays in this other crisis of future sustainability of orders such as the Oblates.

Or not. They could simply, as Benedict XVI attempted with his reform of seminaries and Catholic education, assume that it is possible to imagine a world without homosexual persons and bet everything that said pipedream will solve the problems they face on both fronts.

It is striking that, knowing how important the problem of sexual abuse is, so much so that Pope Francis appointed one of the Oblates as secretary of Tutela Minorum and knowing that their ranks are becoming increasingly smaller, they prefer an approach focused on litigation and deception instead of that proposed by Pope Francis of the so-called “spirituality of reparation.”

The reality is that most dioceses and religious orders in the Spanish-speaking Catholic world, attempt to exacerbate litigation, as their criminal lawyers recommend and, above all, they try their best to bring the victims and their families to the brink of desperation.

The effects of these strategies were detailed, for example, in the series dedicated to abuses in the dioceses of the state of Chihuahua. The text in which the experience of the lawyer of one of the victims of a clergyman from Ciudad Juárez was reported appears linked immediately after this paragraph, although it is only available in Spanish.

One of the problems that emerges in this case is that, even though the Oblate province of Cruz del Sur considered that Fleitas deserved, at least, to be suspended for a year, he and his superiors in Paraguay did not comply with that internal ruling.

He continued celebrating sacraments. He returned to the places where he had attacked one of the faithful who, in good faith, approached him and, as it turned out, even confronted the faithful, blaming them for abandoning the Catholic Church, apparently without realizing that it was his own attitudes that provoke this reaction from the faithful.

Another problem is that the Paraguayan justice system, like those in the rest of Latin America, does not show due interest in cases like this. Perhaps because it remained what in Mexico would be considered “an attempt”, although Fleitas used force to try to kiss his victim whom he, in any case, verbally and spiritually attacked.

The other possibility that cannot be dismissed is that the problem in this case is that the victim is not a young teenager from a wealthy family with the features one finds in the victims of Mexican Marcial Maciel, Chilean Fernando Karadima or those of the Peruvian order known as Sodalicio de Vida Cristiana.

The victim whom Fleitas López attacked, even if it was only attempted, as Mexican legal jargon says, is a female. Civilian laws in Latin America seem to have little interest in preventing such attacks. They minimize them and in doing so, civil and penal Latin American laws normalize such attacks.

A Mexican problem

I learned about this case through the Survivors’ Network of Ecclesiastical Abuses in Argentina. One of its leaders got in touch and provided me with the first elements that told the story of risk of bringing Fleitas López to Mexico.

That possibility was confirmed once a relative of Fleitas López’s victim sent me more information that, in turn, had been provided to him by current and former members of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. These current and former members of the order are not satisfied with the way in which their leaders in the different provinces have approached the transfer of Fleitas López to Mexico.

As far as it was possible to reconstruct his route to Mexico, he would have arrived here at some point in the first half of 2023. Last year the Mexican branch of the Oblates received priests and religious from different parts of the world, so the arrival of a priest from Paraguay would not have raised suspicions.

Already in the second half of 2023 he would have spent part of his time in the seminary or training house that the Oblates have in the state of Puebla, the so-called Vocational House, as the map that appears immediately after this paragraph tells.

On top of spending time at that seminary of sorts, he would also have provided some service in the parish of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the so-called Guadalupita, in the San Rafael neighborhood, of the Cuauhtémoc borough of Mexico City.

In any case, since 2023 Fleitas López has been a problem for the Mexican province of the Oblates. He could become a problem for the diocese of Tehuantepec, and he will surely become a problem for the Conference of the Mexican Episcopate, which continues to focus on a model of very brief therapies, lasting three months, that has not been proved to be efficient.

That Fleitas López has been in Mexico since 2023 was possible to know through to a message sent via WhatsApp. The image is a photograph taken from an internal newsletter of the Oblates in South America provided by a former member of that order to the relatives of the Paraguayan victim, who sent it to me by said app.

Once again, it is not possible to confirm this information because that is the nature of the attitude of the Catholic hierarchy in Mexico. The place where this therapy would have been given is the Rougier Foundation created by the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit in the vicinity of Cuernavaca, Morelos.

Although the center has a website that tells where they are and what they do, it is not possible to obtain information there. The page was last updated in 2020, that is, four years ago.

It is a three-month program and, among the problems it claims to address is to help those who participate to…

…face situations of depression, anguish, addictions, affective, emotional or sexual problems, vocational uncertainty, difficulties in human relationships, existential dissatisfaction, lack of impulse control…

Everything and nothing at the same time, since it seems difficult to assume that any case of troubled clerics will require only three months.

It is notable that the Mexican Catholic hierarchy frequently complains about “false priests,” but Mexican dioceses do little or nothing to prevent abusing priests from practicing the priesthood.

In the Archdiocese of Mexico City, as demonstrated with the priest Sergio González Guerrero, accused of abusing a minor male in the borough of Tlalpan, it was possible to find in the first hours after his arrest the name of that priest in the archdiocese website as the story in Spanish linked above describes.

As was seen in another installment of that series, a few hours later, when the scandal had broken out in the Mexican capital, the name of that priest was removed from the platform of the Archdiocese.

However, smaller dioceses do not have something similar, as was demonstrated in the case of the diocese of Izcalli in the State of Mexico, when the case of Morseo Miramón Santiago was presented in the Spanish-speaking story linked above.

In Mexico, religious orders rarely have a public registry or even a list of the priests who are their members. Orders that usually receive some public scrutiny, such as the Jesuits who work at the Universidad Iberoamericana or the Centro Pro DH can be identified with some ease.

Some of the parishes of the same Company of Jesus, such as that of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Chihuahua City have a Facebook page that is updated very frequently and in a very professional manner, so it is possible to keep track of the Jesuits who work there with relative ease.

However, in the case of the Oblates, although they have a significant number of Facebook accounts and their site has some useful information, it is information more concerned with disseminating what they present as advertisement for their own works and not as information that allows to keep track of their members, as Fleitas López’s case proves.

Despite this, it is known that at the end of last year decisions were made about who would be sent to work at the three parishes that the Oblates head in mostly rural municipalities of the diocese of Tehuantepec, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

The changes in those three parishes would have given the opportunity to the superior of the Oblates in Mexico, José Ariel Martínez Morales, to present the name of Fleitas López to Crispín Ojeda Márquez, current bishop of the diocese.

Tehuantepec was presided from the early 1970s until the first days of this century by now defunct bishop Arturo Lona Reyes.

Ojeda came to be bishop of Tehuantepec only because he was auxiliary bishop of Norberto Rivera Carrera in the archdiocese of Mexico City for seven years. There is no other merit that one can find in his resume than the closeness with the now emeritus archbishop of Mexico who had in Crispín Ojeda one of his most docile collaborators in the country’s capital.

Ojeda arrived in Tehuantepec to replace Oscar Armando Campos Contreras, current bishop of Ciudad Guzmán, in the Western state of Jalisco.

Campos Contreras was a disciple of one of the hierarchs with the most accusations of covering up predatory priests, the now emeritus archbishop of Oaxaca, José Luis Chávez Botello, whose lineage as part of the clique created at the time by the archbishop emeritus of Guadalajara, Juan Sandoval Íñiguez, was the subject of a very detailed analysis in the series that Los Angeles Press dedicated to cases of sexual abuse in Chihuahua, which is available in Spanish and it is linked above this paragraph.

What was said about the dioceses of Chihuahua in that series is also truth for both Crispín Ojeda and Campos Contreras. They have been at Tehuantepec to demolish Lona Reyes’s legacy in that diocese.

Moreover, Chávez Botello, Sandoval Íñiguez, and Rivera Carrera are some of 15 bishops who have been named by Mexican nonprofit Spes Viva and the aforementioned Bishop Accountability as involved in the cover up of predator priests in Mexico.

What Sandoval did in Ciudad Juárez in the eighties, Campos Contreras did in the first decade of this century: demobilizing the work of Lona Reyes, who died four years ago as part of the wave of coronavirus victims.

Neither Campos Contreras nor Crispín Ojeda Márquez prepared Tehuantepec for the reality of sexual abuse. Both, like most bishops who are disciples of Cardinals Sandoval Íñiguez and Rivera Carrera, are betting than the victims will either die or get tired.

Although in theory Crispín Ojeda has covered the process of creating a local commission to prevent abuse, whose decree can be read here in Spanish, the diocese lacks a website or even a Facebook page from which contact can be established with said commission .

The Facebook page that exists under the name “Diocese of Tehuantepec,” available here, uses a personal page format. Not the formats that exist for institutions or businesses.

One can assume that it is indeed legitimate because, from time to time, some decrees or communications appear from the bishop who presides over that religious entity and, in my case, because I have some mutual contacts with the diocese that I know are Catholic hierarchs in Mexico.

But even if one looks on that page for a contact phone number for the commission to protect minors in the diocese of Tehuantepec, you will not find it there. Perhaps in the churches of the diocese there are posters or some other means to know how to contact that commission, but it was not possible to verify it.

That is an important fact to consider because, although in the Oblate curia in Mexico there are those who justify receiving Fleitas López because he has been “discharged” from the therapy given by the Rougier Center in Cuernavaca, Morelos.

It would have been with this endorsement from the Missionaries of the Holy Spirit, another Catholic order, that the superior of the Oblates in Mexico Ariel Martínez Morales presented the Paraguayan Fleitas López to the bishop of Tehuantepec, Crispín Ojeda.

As far as it was possible to know, he would have authorized his integration into the team of priests who serve the parish of Santa María Magdalena Tequisistlán in the municipality of Magdalena Tequisistlán, Oaxaca.

And although that municipality is far from being the poorest in Oaxaca, it cannot be considered an opulent place or one where opportunities abound.

The 2015 reports of the then Secretariat for the Social Development (available here), and 2022 from the now Secretary of Welfare (available here) agree that it has a low degree of social underdevelopment. Although it should be clear that this estimate only corresponds to that municipality and the territories of the Catholic parishes hardly coincide with those of the municipalities. Catholic parishes in that part of rural Mexico usually integrate several municipalities, more so in Oaxaca, where municipalities are extremely small.

It is not possible to develop an analysis of the conditions that mark the life of municipalities such as those of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec today. Suffice it to point out that although the educational gap and other indicators are better in Tequisistlán than in the rest of Oaxaca, it is very likely that the territory of the parish includes other populations that are not as fortunate as they would seem to be, at least on paper. the municipality where the main temple of that parish is located.

In that sense, it must be clear that a priest accused and convicted in his country of sexual abuse is sent to an eminently rural parish after having enrolled him in a therapy that, according to those who lead it, lasts three months.

The possibility of Fleitas López returning to his priestly duties did not go down well in Paraguay, neither inside nor outside the Oblates, as there are those who are aware of the seriousness of the appointment.

They did not immediately turn to the media. Far from it, they did everything as recommended, but, for some reason, their complaints did not find echo in the Oblate leadership who are more interested in recycling Fleitas López regardless of the damage he does in Mexico.

Paraguay-Rome-Mexico

Among the many papers that have made the trip from Paraguay to Rome and now to Mexico, the relatives of the Paraguayan victim sent me four documents.

All of them respectful, without anything offensive either in the Spanish commonly used in Paraguay or in any other dialect of Spanish in Latin America. The four documents are addressed to Louis Lougen, the American priest who has presided, since 2010 and until now, over the Oblates on a global scale.

Before presenting these documents, it is necessary to introduce the first response that the victim’s relatives received from Fleitas López’s superiors who reside in Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina.

This official communication from the Oblates prohibits Fleitas López to celebrate mass or other sacraments for at least one year.

Fifteen days later, on July 15th, 2021, the residents of General Artigas sent a letter to Superior Lougen in Rome.

That has been the only document sent by the victim’s relatives that has received a response from the American clergyman who leads the Oblates on a global scale.

In that document, the neighbors already warned Lougen about the way Fleitas López acted at Our Lady of the Rosary, the Catholic parish in General Artigas.

They showed that Fleitas López was not complying with the suspension that had been imposed on him by the provincial from Buenos Aires two weeks before, on July 1st, 2021.

Lougen responded until August 6th. More than fifteen days later. His response admits having received the document from July 15th but, as the messages from 2022 demonstrate, there was no change in Fleitas López’s attitude or those who support him among the Paraguayan Oblates.

Of the three paragraphs of his response only one sentence is worth reproducing here, although the neighbors’ fourth communication and Lougen’s response in Spanish can be viewed as a PDF file immediately after this paragraph. He says verbatim “The allegations you have made are very serious and will be investigated.” The rest is ecclesiastical jargon.

Since then, the victim’s relatives have sent other three documents to the Oblate leaders. The first on December 13th, 2021 (appears as 2020), which was accompanied by links to two local media outlets in Paraguay, which reported on the activities of Fleitas López. He had just been denounced and it is assumed that he was suspended from celebrating the sacraments, including mass.

A Paraguayan newspaper mocks what Fleitas López said with an expression in Guaraní, one of Paraguay local languages.

The expression is “ndajeko” and is often used in a similar way to the way English-speakers use the expression “Are you kidding me?”. “Ndajeko” reveals the astonishment that Fleitas López’s imposture of reproaching the faithful who had the misfortune of attending the mass that he celebrated that day in December 2021 caused in the reporter and editors of the newspaper Crónica de Paraguay.

What is worse. Far from showing any regret for the way in which he abused one of his faithful, he reproached the faithful’s attitude towards the Catholic Church, how they distance themselves from the Church and look for other churches or abandon religious practice altogether.

The second is a brief text of four short paragraphs, dated July 3rd, 2022, which appears as an image immediately after this paragraph in Spanish, with the signature of eight people, in which they inform Lougen that Fleitas López is touring General Artigas to warn him of the risk that this poses.

The third was signed on July 12th by a minimum of 25 residents of General Artigas who made Fleitas López’s superior see that, despite the precautionary measures that the Paraguayan District Attorney had issued, the priest decided to approach persons who live near the victim.

What is worse, in the penultimate paragraph of the letter they make him see that the internal investigation, the one carried out by the Cruz del Sur province of the Oblates, was flawed from its origin since it was carried out by “former seminary classmates and former teachers of Fleitas López” who “did not act impartially.”

None of the three documents sent to Oblate Superior General Lougen merited any response from him or those working in his office in Rome.

The problem, of course, is that the case has not advanced in Paraguayan courts. Nor has it advanced on the canonical route, which is the responsibility of the curia of the Oblate province of Cruz del Sur in Buenos Aires and the global curia of that order in Rome.

Now, with the arrival of Fleitas López to Mexico and his eventual incorporation into the clergy of the diocese of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, the chances of justice for Paraguayan victims are reduced and the risk of more victims of sexual abuse in Mexico increases, especially in Oaxaca.