VATICAN CITY (VATICAN CITY)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

March 15, 2024

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

Appointments, departures, exchanges, and meetings in the 41st year of the clerical sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church

In Rome, the only hope for victims is the appointment of Col. Teresa Morris Kettelkamp, a retired Illinois police officer, to the commission to prevent abuses.

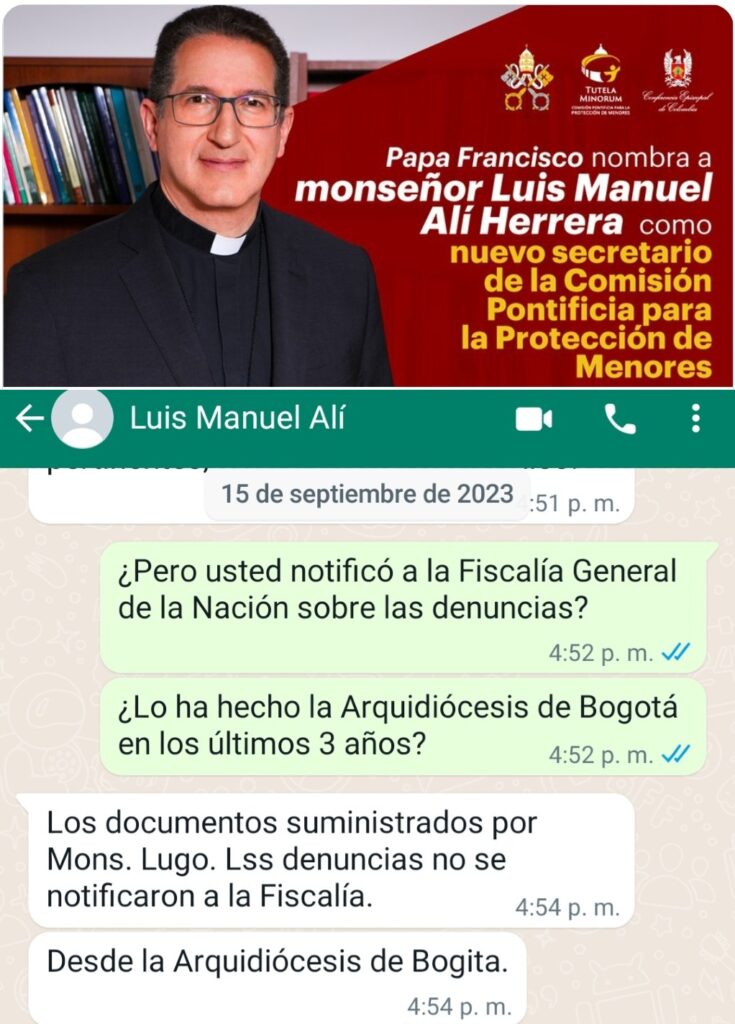

The new secretary general, the auxiliary bishop of Bogotá, Luis Manuel Alí Herrera, lacks any record that speaks of interest in resolving the sexual abuse crisis.

The most relevant news in March regarding the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church were the appointments, on March 15, the day that used to be called Ides in the ancient Roman calendar, Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, known as Tutela Minorum or simply as Tutela, by its name in Latin.

Although these appointments could be seen as signs of some movement on this matter, the reality is that the solution to the crisis is rather far away despite the fact that we are now entering the 41st year of this crisis as the key issue in the public debate of what Catholicism is and can be.

More important than this, however, are the effects of this crisis on the lives of the victims that continue to accumulate.

The new appointments contain many of the paradoxes marking Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s performance as Pope, Supreme Pontiff, and as such responsible for these matters. In a sense, the commission for the first time has a secretary who is also a bishop.

That will make many of the bishops who until now did not bother to respond to the calls or emails of Andrew Small, now emeritus secretary at that commission, feel obliged to do so because the communication is signed by the new secretary, the Colombian. Luis Manuel Alí Herrera, who has been—since 2015—auxiliary bishop of Bogotá.

But perhaps that would not be enough. That is why nuncios must be archbishops so that the archbishops in the countries where they hold office do not disdain them.

The absurdity of it is that, in that logic, Pope Francis will have to appoint Alí Herrera as archbishop so that other bishops pay attention to his messages. Even appont him Cardinal, so that an arrogant Cardinal will think twice before dismissing his messages.

That is the sad reality of Catholic clericalism: there are cardinals and archbishops who, drunk on narcissism, do not feel obliged to respond to messages from clerics who are beneath their rank.

Main problem is that there is no way for Pope Francis to appoint the new secretary general deputy in the Commission as an archbishop or a Cardinal since Teresa Morris Kettelkamp is a female.

You’re not in Kansas anymore, Teresa

Col. Teresa Morris Kettelkamp is a retired colonel of the Illinois State Police in the United States, where she was an expert, among other things, in the forensic analysis of crime scenes and where she was recruited by the USCCB, the Conference of Catholic Bishops of the United States, as an expert criminologist.

As such, she has dedicated the last ten years of her life to helping the Catholic bishops in her country and, since 2016, bishops globally, to develop principles and norms to prevent sexual abuse.

I do not think her appointment will be enough, because even though as deputy secretary of Tutela she will be able to improve the Catholic Bishops’ tone and attitude, while preventing a bishop from using medieval slang to talk about sexual abuse, Morris Kettelkamp will not head anything resembling a “task force.”

In other words, she will not investigate the many pending cases of clerical sexual abuse, nor does she have, strictly speaking, powers over the just under 2,500 Catholic dioceses that exist on a global scale.

She may, however, advice the bishops to avoid this or that mistake. Despite this, I believe that his experience as a police officer in real life in a country where victims have a chance of finding a measure of justice makes her appointment positive and could lead to have an impact in the future.

The problem is how far into the future. Beyond the fact that, as demonstrated in two of the most recent installments of this series, there are priests who pray—albeit hypocritically and sardonically—for the death of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the reality is that the bishops continue to bet on victims of sexual abuse either die or get tired as to avoid litigation.

To achieve this, they even encourage the most faithful of their faithful to attack the victims on social networks, demanding that they air their cases there, knowing that—at least in the case of the Mexican victims—this would imply spoiling their judicial processes and even would give diocese lawyers the chance to counterattack the victims of sexual abuse.

To do this, they would cook a crime that very solicitous district attorneys and judges would be willing to prosecute at the speed of light to protect the “good name” of the priests and incidentally cause the other processes to sink.

Given the restrictions set by reality, Colonel Morris Kettelkamp’s appointment to Tutela Minorum will be the only good news for victims of sexual abuse.

That one must follow this line of reasoning when talking about Tutela Minorum is worrying since it is an institution that must face what is the worst crisis of confidence in the history of the Catholic Church in the last 70 years and, as was seen in a previous installment of this series, available only in Spanish and linked immediately after this paragraph, if something has characterized Tutela Minorum it is that it has increased distrust in the Catholic Church.

Con voz propia

It is known that Alí Herrera is not good news for the victims and their relatives, because—as the Colombian press specialized in following these matters has shown—the auxiliary bishop of the capital of that country is not known by his interest in protecting the victims.

Not even in reporting the cases of sexual abuse to the Colombian authorities, as demonstrated by a message on the social network formerly known as Twitter by the Colombian journalist Miguel Ángel Estupiñán, linked immediately after this paragraph.

In that message Estupiñán takes a screenshot from his WhatsApp account to show Alí Herrera’s response to a specific question about the reports given to the Colombian authorities. There, the newly appointed general secretary of Tutela makes clear that there was no reporting.

He is worried, as it is often the case with clerics, with the Church, his institution. Victims and their families are and afterthought of sorts for clerics.

The Castrillón Doctrine

That the priority of the Colombian bishops is the clerics is something that the late Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos made more than clear back in 2001.

That year, Castrillón had the dubious honor of boasting in public, with John Paul II’s permission, the way he had congratulated Pierre Pican, a member of the Salesian order who became bishop of Bayeux-Lisieux in 1988. He has the “privilege” of having been found guilty by French authorities of covering up a sexual predator priest in 2001.

And Bishop Pierre Pican did not cover up for just any priest, one who had committed an indiscretion. Pican covered up for René Bissey, accused in 1996 and convicted in 2000 by the French authorities after having abused at least eleven minor boys between 1989 and 1996, as narrated in this article from 2000.

It was in 2001 that Castrillón sent a letter in French, with the letterhead of the then Congregation for the Clergy of the Holy See, which he presided over. The letter congratulated Bishop Pican for covering up for the priest.

That has been, at least since the end of the 19th century, a kind of unofficial doctrine of the Catholic Church. The doctrine that Castrillón showed in his 2001 letter was not his. He only has the dubious merit of having made public the existence of this way of understanding the problem.

He did it in two stages, first with his 2001 letter, verified as real in 2010 by the then spokesperson of the Holy See and current director of the foundation recently created in Rome to honor the memory of Benedict XVI, the Italian Jesuit Federico Lombardi.

Then he confirmed it with the statements he made in 2010 when some raised questions about that letter that, even if he had wanted to, he could not deny. On top of that—far from accepting any mistake, he jumped at the chance to throw himself to attack one of the windmills of Catholic mythology: “freemasonry”, which he accused of attacking the Catholic Church with the cases of sexual abuse, as can be read in this 2010 article from the Colombian magazine Semana.

Alí Herrera, the new secretary general of Tutela, was already a priest at the diocese of Bogotá when Castrillón accepted his role on the Bissey scandal. In a rational universe, this would make him aware of the consequences of Castrillón’s behavior, but it is not clear to me that this is the case.

I wish that it would lead to an explicit renunciation of the “Castillón doctrine” of mutual concealment of the clerics, but there is an objective risk that from his new position in Tutela Alí Herrera will simply apply his knowledge as a psychologist so that, faithful to the “Castrillón doctrine” the bishops develop more twisted ways to cover up for other Catholic clerics and to blame the new favorites of Catholic mythology: feminism or gender theory.

No matter how optimistic one is, beyond the arrival of Morris Kettelkamp as the newly created deputy secretary general of Tutela Minorum, it is very difficult to find any substantive progress in the crisis that started back in mid-1984, when Jason Berry began to peel the onion of this reality with his reports on sexual abuse in the dioceses of Louisiana, United States.

It is true that there have been changes that demonstrate that Pope Francis understands the mechanisms that allowed the most notable Latin American sexual predators to purchase the institutional protection of the Roman curia during the pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

The problem is that these institutional reforms, which have to do with the structure and functioning of the Secretary of State and the bank of the Holy See, do not solve much more urgent human problems that touch the lives of thousands of victims of sexual abuse across the country. global scale.

The reforms, for example, took away from the Secretary of State the privilege it had during the administrations of Angelo Sodano and Tarcisio Bertone, of having its own assets and budget. This will be useful so that future Secretaries of State of the Holy See cannot receive, as Sodano did, bribes from sexual predators such as Marcial Maciel, Fernando Karadima or Carlos Miguel Buela.

However, it is not clear to me what the Catholic Church will do with cryptocurrencies which, for reasons that would be hard to explain in this piece, like the most recalcitrant sectors of the Catholic right.

The problem with the reforms made so far by Pope Francis is that they do not solve the problems of the victims of predators that operate in countries like Mexico and the rest of Latin America, notable for the ineffectiveness and slowness of their systems of justice.

The reforms in the bank of the Holy See, which allowed it to fully reintegrate it into the financial system of the European Union, have positive effects since they introduce principles of transparency that did not exist before in that bank, but they do not contribute to the solution of the problems of the victims of sexual abuse who face the consequences of that abuse.

These are advances that are also worthy of attention for those of us who—for whatever reason—have specialized in these topics. But no one could say that they are the solution to the problem of sexual abuse. They make it difficult for the Holy See banking system to be used to bribe officials of the Roman curia, it is a good gesture by Pope Francis, but it does not address the concrete problems of victims of sexual abuse.

It is necessary to acknowledge that even the Episcopal Council for Latin America and the Caribbean, the so-called CELAM, the highest body of the Catholic Church in the region, has been unwilling to explicitly acknowledge the scope of the crisis in the region.

In Latin America, only the Chilean bishops have acknowledged a deep sexual abuse crisis, and it was only after the embarrassment caused by Pope Francis’ disastrous visit to that country.

The Pope paid for his own and other people’s mistakes during that visit. Still during his trip to Chile in 2018, Francis made a last effort to defend, against all logic and with arguments that ranged from fallacy to absurdity, his decision to appoint Juan Barros Madrid, as bishop of Osorno, Barros Madrid’s known association with super predator Fernando Karadima.

Although at the beginning of this month the members of the so-called Center for the Protection of Minors of Latin America, Cepromelat, met in Panama, their meeting was notorious for the obsequious mutual praise that their community managers on social media dispensed to the members of that commission than by some real, tangible, change in the way that entity operates as Tutela’s counterpart in Latin America.

If one was reading nothing but those social media accounts and how they praise their own members, one might assume that they have solved the problem, but reality begs to differ.

Mutual praise in Panama

On March 6, for example, Cepromelat’s Facebook account presented the activity they held from the 12th to the 14th of this month in Panama, describing their speakers as “incredible.” It is impossible to find evidence that justifies the use of such a disproportionate adjective, but there it is, as a testimony of what in Mexico we call “the guayabazo”, self-praise, the proverbial “praise in one’s own mouth”, as one can see in the image that appears immediately after this paragraph.

Four days later, a message dated March 10th on that same social network, Cepromelat moderated the praise it gave itself and no longer showered their speakers with praise, as the following image proves.

The problem, of course, is that they were unwilling to provide a full account of said speakers.

Although some of them could be experts on the topics they are talking about, Cepromelat is not straightforward about the associations of some of these speakers, especially those who render themselves as laypersons, but who are more clericalist in the way they understand the Church and the sexual abuse crisis than many clerics.

Far from it, they are interested in defending the institution at any cost.

The most notable case is once again from Colombia. That is the case of Mrs. Ilva Hoyos Castañeda, who appears as a Doctor of Law, a degree she obtained from the University of Navarra, a property of Opus Dei, an “order” with which Mrs. Hoyos Castañeda has some of the secret associations that Opus Dei has created throughout its history and that allows it to pass off as lay people those who, in more ways than one, are more clericalized than the clerics themselves.

In a response that Dr. Hoyos sent to a news story published by the Religión Digital, a Website published from Spain, about the sexual abuse crisis in Colombia, Hoyos Castañeda presented herself as a victim (available here) of journalist Miguel Ángel Estupiñán who, based on the existing legislation in that country, has shed some light on some of the many cases of sexual abuse, which are reported in a book titled El archivo secreto (The Secret Archive), recently published in Colombia.

The story by Estupiñán that provoked that reaction in someone who is also an advisor to the national conference of Catholic bishops of Colombia is available here.

However, Estupiñán’s greatest merit is that he has shown how much the Colombian Catholic hierarchy, with the help of lay people like Mrs. Hoyos, has managed to come to light as far as the true scope of the crisis is concerned, mostly because of the virtual absence of mechanisms for accountability of the Catholic Church in that country.

Meanwhile, in Buenos Aires

At the same time as the Cepromelat meeting in Panama, in Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, networks of survivors of sexual abuse in Latin America had their own meeting.

The meeting was convened under the motto “In our words: First regional meeting between Latin American survivor organizations and allied organizations” and was organized by the Argentine organization Aralma, the global Child Rights International Network, the A Brezee Of Hope foundation (available here) and by the Movimiento Bravo, the Latin American branch of the global Brave Movement.

Without the mutual self-praise that abounded in Panama, survivors realized the extent of their own ability to manage the devastation caused to their lives by sexual abuse at the hands of Catholic clergy. They also talked about what they hope to achieve in the future, as can be seen in the statement they published before the meeting (available here), as well as on the social media accounts of the Argentine Survivors Network (if it is not displayed after this paragraph that message is available here as well).https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2FSobrevivientesdeAbusoEclesiasticoArgentina%2Fposts%2Fpfbid0vjrfNkE2EuKKaX9HvozrEDsizc4QRfJwwzxoFMvZUHE9gdSLhkUAL6wqXvodo2Wzl&width=500

There were, among others, José Enrique Escardó Steck, a survivor of abuse at the hands of the Sodalicio de Vida Cristiana, an “order” that emerged in Peru in the early seventies of the last century to which a couple of installments in this series have been dedicated, one of which is linked immediately after this paragraph.

Con voz propia

El Sodalicio y el laberinto del abuso sexual en Perú

Marcela Orellana, from the Argentine survivors’ network, was also there. She is the mother of one of the victims of abuse at the Próvolo Institute. That school, located in the province of Mendoza, created to care for minors with speech and hearing problems, priests, nuns and lay people linked to the Company of Mary, a religious order with a presence in Italy and South America, abused minors under their care.

Although some of the clerics were convicted, other defendants were exonerated by the Argentine justice system back in October 2023.

And it must be clear that Pope Francis is aware of the fundamental problem in the Catholic Church on a global scale. On March 7th, at a meeting with the leadership of Tutela Minorum in their Rome headquarters, the Pope proved so.

Whoever can read the message in English, Italian, French, Portuguese, or German will be able to realize that, indeed, the Pope acknowledges that the Church must take care for the victims of clerical sexual abuse.

His message that day was “it should not be that the victims do not feel welcomed and heard.” And he is right. Sadly, the bishops who in theory should obey are unwilling to do so.

The situation is as bad that the Pope’s speech that day at the Tutela Minorum headquarters in Rome does not appear as translated into Spanish yet at noon on Sunday, March 24, 2024, when I write these lines, as you can see in the image that immediately after this paragraph.

And, to be clear. I do not need a translation to make my job easier. I read without any problem in Spanish and English. With minor problems in Italian, Portuguese, and French, in that order of comprehension, and with problems in German. I know how to use Google Translate or the equivalents of other online translation services.

The problem is the implicit message that Rome continues to send to the Spanish-speaking Catholic world regarding the crisis of sexual abuse, which remains the same as the one drilled from Rome during previous pontificates: the crisis of sexual abuse does not exist in the Catholic Spanish-speaking world.

That this occurs during the pontificate of the first pope whose mother tongue is Spanish in the last 450 years, only demonstrates the involuntary black humor of the Catholic hierarchy, whose message continues to be that some victims, those who speak English, French, German or some other language, deserve the attention that the victims in Latin America and Spain do not get.

Understanding

It is notable, in this sense, that one of the relevant topics of the Tutela meetings from March 5th through 8th, when Pope Francis delivered that message that does not deserve the benefit of a translation into Spanish, was the signing of a series of Memoranda of Understanding between Tutela as responsible for this issue at the Holy See and some dioceses and religious orders.

In Mexico, the memorandum was signed by both the Primate Archdiocese of Mexico and the Conference of Major Superiors of Religious of Mexico, the CIRM.

The instrument, which is available in Spanish as a PDF immediately after this paragraph, is positive to the extent that it recognizes, for example, the existence of “Victims and Survivors (V/S)” as a category that deserves special treatment from of the entities that reach these agreements with Tutela.https://www.losangelespress.org/view-pdf/?url=/__export/sites/lapress/pdfs/2024/03/24/WLm4oE0axgZwpscT.pdf

Memorandum of Understanding between Tutela Minorum and the Primate Archdiocese of Mexico and the Conference of Superiors of religious orders in Mexico.

The problem, however, is that Tutela Minorum lacks the “teeth” to force all other Mexican dioceses to sign similar documents. What is worse, I did not find in the document signed by Cardinals Sean O’Malley, on behalf of Tutela Minorum, Carlos Aguiar Retes, as primate archbishop of Mexico and Sister Juana Ángeles Zárate Celedón, as chair of the so-called CIRM, the “teeth” that could force the signatory parties to comply with what they agree to there, which is a minimum of dignity and respect for those who try to denounce their sexual predators.

Like any Memorandum of Understanding, it expresses the wishes of the parties, but there is nothing there that guarantees any solution for the victims of sexual abuse in Mexico, who are not even those of the entire country. They are only those of the Primate Archdiocese of Mexico and those that could denounce a priest linked to any of the religious orders that belong to CIRM.

In other Latin American countries, notably Costa Rica, Panama, Paraguay and Venezuela, the signatory party is the national conference of bishops of each of those countries, but with Mexico and Argentina, the signatory parties are the individual dioceses, as can be seen on the page available here.

And even worse. In the case of Mexico, it has only been signed with the archdiocese presided over by Aguiar Retes and in the case of Argentina, it has only been signed with the marginal diocese of Rawson, in the province of Chubut, rather far from Buenos Aires or Córdoba, the two largest metro areas of that country.

The implicit risk of this model based on the good will of the bishops is that, currently, in Mexico, less than half of the dioceses affiliated with the Conference of Mexican Catholic Bishops have created their commission to prevent, not to resolve, only to prevent cases of sexual abuse.

If the signing of each memorandum of understanding with the Mexican dioceses is going to advance at the pace that the creation of commissions to prevent abuse has advanced, there will be Mexican dioceses that will continue without such a commission in the 22nd century.

The image that appears a little after this paragraph comes from the page of the National Council for the Protection of Minors on the Web portal of the Conference of Mexican Catholic Bishops. It shows the commissions that had been created until noon on Palm Sunday of this year, March 24, 2024.

The image takes as they exist in that page the coats of arms of each of the 48 Mexican dioceses that have created this commission. The commission no. 49 does not correspond to a diocese, but to the order of the so-called Marist Brothers, which is the one that appears until the end. The other 51 Mexican dioceses have not had the time or desire to comply with this requirement instituted by the Pope Francis as part of the response to the sexual abuse crisis.

And in addition to the notable absence of translations into Spanish of many of the messages delivered by John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis on the sexual abuse crisis, or the unwillingness of the Mexican bishops to create the diocesan commissions to prevent abuses, there are countries in which there is a known public record of sexual abuse where the Catholic Church has never publicly accepted that there is a sexual abuse crisis.

In Latin America, only the Chilean bishops have accepted that a crisis of this type exists in their country.

In Mexico, the Spanish-speaking country with the largest number of Catholics on a global scale, this has never happened. In Mexico, by the express wish of the Conference of Catholic Bishops, none of the three popes visiting Mexico in 1979, 1990, 1993, 2002, 2012 and 2016, have ever accepted the very existence of a crisis or made any kind of statement regarding the sinister characters like Marcial Maciel (Legion of Christ), Eduardo Córdova Bautista (Archdiocese of San Luis Potosí), Nicolás Aguilar (diocese of Tehuacán, Archdiocese of Mexico and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in the United States) or Gerardo Silvestre Hernández (Archdiocese of Oaxaca).

It is worth remembering that dialogue with victims of sexual abuse has been central in some of the visits of the last three popes to countries such as the United States in 2008, Malta and the United Kingdom in 2010 or Germany, in 2011, to cite the most obvious cases, regarding the pontificate of Benedict XVI.

It is true that only in the case of the visit to Malta there is a public and official record of Benedict XVI meeting with victims of abuse, since the activities in which he did so in Washington, DC, in 2008 and in Berlin in 2011, were private and there are only partial journalistic records.

It is notable, however, that there is a public and official record of the meeting with the victims in Malta in the archive of Ratzinger’s pontificate, which can be consulted by those who speak Italian, French and English, as can be seen in the image of that page (available here) which appears as an image a little later.

The text of that meeting in Italian is available here and in French here. There is a link that does not work now to an English translation, but what there has never been a Spanish translation of the message delivered by Joseph Ratzinger on that visit to the Mediterranean island.

To add insult to injury, of all the other activities in Malta there are translations into Spanish and Portuguese. The only one in which Spanish and Portuguese are absent for the very professional teams of translators at the Holy See is for the one related to sexual abuse in Malta, as proven by the image on that page appearing immediately after this paragraph.

And—as already demonstrated—this tendency to exclude Spanish from the translations of pontifical activities that have to do with the sexual abuse crisis is a reality still present, eleven years after the beginning of the current pontificate and in the 41st year of the crisis of sexual abuse.

Disdain and arrogance

The disdain and arrogance, mixed with the self-praise with which the Catholic hierarchy insists on confronting the crisis of sexual abuse in the Spanish-speaking world, makes the politicization of the issue almost unavoidable.

I would not predict how long it will take for politicization to happen. I am clear, however, that the bishops and superiors of the religious orders are betting that the victims die so no politicization happens, and it is a shame that this is the case.

Although the Catholic hierarchy has a determining role in this problem, it is not the only one that benefits from the current situation in Latin America. It is true that in some countries, such as Mexico and Chile, sexual crimes no longer prescribe, but any of the countries in the region are far from following the experience of the state of New York in the United States by opening what they called a “lookback window.”

Said window allowed victims who remained silent for decades to bring their grievances before the district attorney. It is difficult to evaluate what will happen in that state of the United States, since the judicial processes derived from such windows has just begun.

And not all measures at the level of legislation have to be as “revolutionary” as the one from New York state. In Mexico, for example, it would be enough to correct the “imperfect” design of the regulations that mandate the leaders of an institution to report cases of abuse to authority.

The obligation already exists, but it exists without establishing a precise deadline for the reports. The vagueness of this aspect of the norm and the fact that the law set no punishments for those who fail to comply with it means that this kind of “period of grace” that exists in Mexico is used to cover up, so that “no trace is left” of the attacks on the faithful.

Such approach in the law helps the Catholic clergy to put pressure on victims and/or their families with the idea of accepting therapies with psychologists or psychiatrists paid and chosen by Catholic dioceses who, of course, will do everything possible to “discharge” the victims as quickly as possible. Clergy and their lawyers also use this approach to blame the victims and for covering up the appearance that minimum standards exist.

What I say in the previous paragraph is not an opinion. I documented it on the story about Joana Cruz Galván, a victim of the clergy of the diocese of Atlacomulco in the State of Mexico, available only in Spanish, which appears linked immediately after this paragraph.

México violento

Joana, víctima de abuso, exige justicia a las autoridades mexiquenses

Joana must face both the disinterest of the Mexican Judiciary with her case, reflected in the fact that there has been no resolution since she denounced it at a press conference at the end of last year, and the audacity with which the bishop of that diocese, Juan Odilón Martínez García has allowed the priests accused by Joana Cruz Galván to celebrate sacraments again in that diocese of the Catholic Church in Mexico.

Last week I wanted to publish this story about the changes occurred in the sexual abuse crisis.

My plans changed when, from Argentina, I got news about the attempt—still uncertain—of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, the Oblates, to bring Rafael Fleitas López to Mexico. He is a Paraguayan priest who was accused by a victim and whose case was reported in the previous installment of this series.

That the Oblates are still using the so-called “geographical solution” to sexual abuse in Latin American countries just proves how far the Spanish-speaking Catholic world is from the English, French or German-speaking Catholic worlds, where there is already a clear awareness of the disastrous effects of these clerical games of musical chairs.

That this “geographical solution” is attempted by the Oblates, the order to which Andrew Small belongs, who until March 15th, the day of the “Ides” in the ancient Roman calendar, was the secretary of Tutela Minorum, is a painful example of the unwillingness of that order and of the Catholic hierarchy as a whole not to acknowledge the magnitude of the crisis.

In doing so, the Catholic has the ever present help of the political elites, the ones in charge of writing, approving, and enforcing our laws in countries that, far from accepting the seriousness of this problem, are betting, from Mexico down to Chile and Argentina, on the problem disappearing on its own.