FARMERS BRANCH (TX)

Baptist News Global [Jacksonville FL]

May 5, 2024

By Jeff Brumley

The all-encompassing nature of church life can provide predators with the ideal cover for committing sexual abuse within congregations, abuse survivor and author Christa Brown said.

“Access and trust. Pastors and churches have both access to kids and enormous trust within the community and within the church,” Brown said during a recent “change-making conversations” webinar hosted by Baptist News Global and moderated by BNG Executive Director Mark Wingfield.

Likewise, that trust makes it difficult for many to believe victims when they come forward, said Brown, who as a child was sexually abused by the youth pastor of her Southern Baptist congregation in Farmers Branch, Texas.

“People would like to believe this happens to kids who are lax in morals, but nothing could be further from the truth,” she said. “The truth is, what made me the most vulnerable to this type of predator was my own faith.”

Brown’s abuser exploited her devotion to the church, its ministers and culture of male authority to commit repeated assaults without repercussion, she explained. “It was the very fact that I loved God so much that made me vulnerable to his abuse, and that’s what makes this crime so terrible, because the kid is left with the sense that God has willed this and wanted this. And in some cases, as with me, I was actually told that.”

Exposing predators and the churches that enable them has been a calling for Brown since disclosing her abuse in 2009. She launched the blog StopBaptistPredators.org and a public database of confessed, credibly accused and convicted Baptist clergy sex offenders.

The attorney also shared her experiences in This Little Light: Beyond a Baptist Preacher Predator and His Gang, and in her brand-new book, Baptistland: A Memoir of Abuse, Betrayal, and Transformation.

Wingfield said one passage in Baptistland that struck him was about “the constant barrage of scriptural justification for why you needed to submit to the predations of this youth pastor.”

Brown said that use of Scripture was actually part of the grooming process by her abuser, in addition to his efforts to desensitized her and other girls in the congregation to sexual talk and sexual innuendo.

“Scripture was used to teach us to be submissive, certainly to teach me to be submissive,” she said. “I think that’s what I would really hope people might realize from my book — just how horribly faith itself can be weaponized for the most unholy of ends.”

Her abuser had a biblical response whenever she balked at his advances, Brown explained. “He would say, ‘Where would we all be if Mary had not been willing to do what God wanted of her, even when she couldn’t understand?’ And as a kid raised in the faith, that was something I thought about. I mean, yes, faith is beyond our understanding. And so, I tried to be like Mary, not that I thought I was going to give birth to a Christ child, but I wanted to be Mary in the sense of having a very strong faith. I thought that was a good thing.”

Another contributor factor to the abuse was a “very authoritarian” church and home culture with strictly delineated roles for boys and girls and men and women. Ministers were to be obeyed without question, Brown said.

“From toddlerhood onward, I was indoctrinated in the belief that these were men of God and that it was my role to be submissive and it was my role to accept what they said, not just because they were men, but because they were carrying the authority of God.”

In that way, her desire to love God with all her heart and soul helped set the stage for her sexual abuse and compelled her to remain silent.

“With that kind of indoctrination, I can’t imagine how I could have done anything other than what I did,” she said. “That was the fishbowl I lived in. That was my whole environment. It was scriptural — ‘lean not to your own understanding,’ ‘obey them that have the rule over you for they watch over your souls,’ which was kind of important if you thought your soul might otherwise burn forever in hell.”

Few realize today the authority Baptist pastors commanded in their communities during the 1960s when Brown was being abused, noted Wingfield, who also was raised from birth in Southern Baptist churches. In addition to preaching, they often functioned as chief counselors or tribal chiefs, he said.

In her new book, Brown relays how her mother sought their pastor’s permission for Brown to spend a summer in Germany after winning a writing contest. While permission was given, the experience of wondering if he would approve was horrifying, she said.

“I mean, that’s crazy,” Wingfield said.

Crazier, still, was the day Brown called the police when her abusive father held one of her sisters in a chokehold — and the police showed up and promptly called their pastor to come over.

When the pastor arrived at the house, Brown said, “he sat around the table and prayed with us. And even as a kid, I knew there was just something not quite right about it, because one of the things he said was, first of all, don’t rile your father up — as if any of us could do anything to prevent my father’s rages.”

The pastor then explained the family should be equally concerned about besmirching the image of a good Christian family by calling the police in such matters.

“As a kid who had just had the audacity to run to the phone and call the police, hardly believing I’m even doing it, I was terrified by the idea that I should have been thinking about what people would think. Even as a kid, I knew that no, there was something wrong there. And yet we all took the pastor as being the voice of authority.”

Wingfield said he was left speechless in reading that her church’s music minister knew of the abuse Brown was suffering but didn’t report it.

Brown said that represents one of the most devastating betrayals she experienced in the ordeal: “The music minister knew. He knew because the youth pastor himself had talked about it with him. And the music minister did nothing other than to say, ‘Don’t do that anymore.’ So, he allowed the abuse to escalate. The worst of what happened to me happened after the music minister already knew.”

That experience reinforced the messaging she received at home and at church to avoid actions that could embarrass the congregation or her family, she said.

“The whole idea of ‘We can’t talk about this because it would reflect poorly on the church’ becomes an ongoing mantra in your story,” Wingfield added.

Brown added that the cloud of denial around church sexual abuse has motivated the vicious responses she has endured since going public with her story.

“I realize these stories are really dark and awful stories, and I think that is why many people seek to deny the reality of them,” she reasoned. “Because we don’t like to believe that such dark and awful things happen, and certainly people of faith don’t like to believe that this faith they hold dear in their own hearts, this faith that has meant so much in their lives, can be used in such awful and twisted ways. So, people wind up denying it because it feels as though to admit that these awful things happen will somehow diminish their faith.”

One tactic abuse deniers use is to question the accuracy of her memories of events that occurred during childhood, Wingfield observed.

But Brown said her story has been corroborated by the music minister and eventually by her abuser who expressed concern that he had been seen by a church member in a compromising situation with her. Her abuse was also backed up by a Baptist General Convention of Texas file of clergy reported for abuse by their churches.

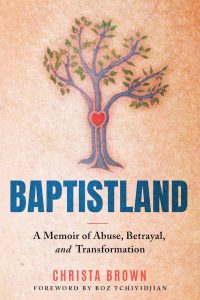

Wingfield asked Brown to explain her new book’s cover art — which is an image of a tree with blossoming branches and a red heart at its center.

“What you’re looking at there is a photograph of my skin and a rather large tattoo,” she replied.

“I view it as not only as a celebration of getting through my ordeal with cancer, but representative of surviving everything else that had been done to me in Baptistland, done to my soul, done to my body. And so that’s what the tree is.”