GREAT FALLS (MT)

Washington Post

May 29, 2024

By Dana Hedgpeth and Sari Horwitz

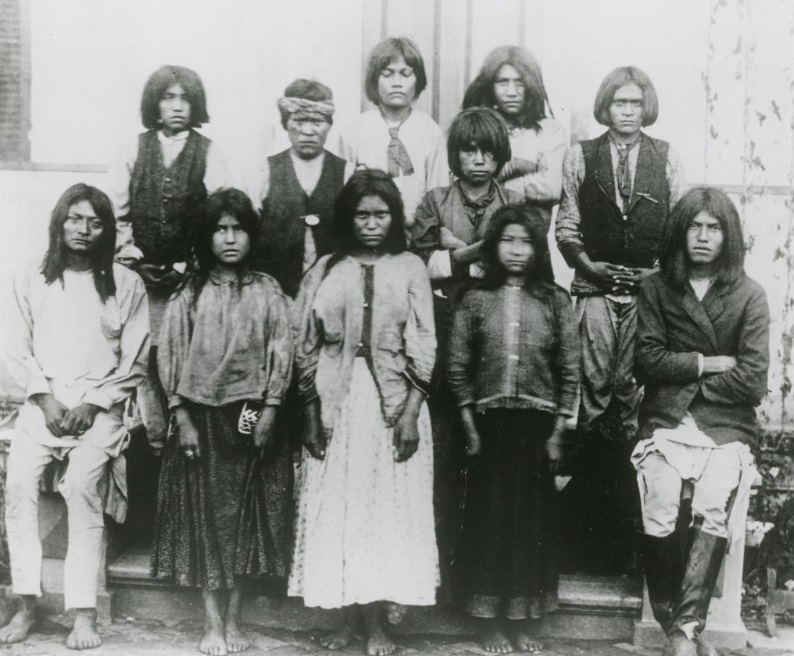

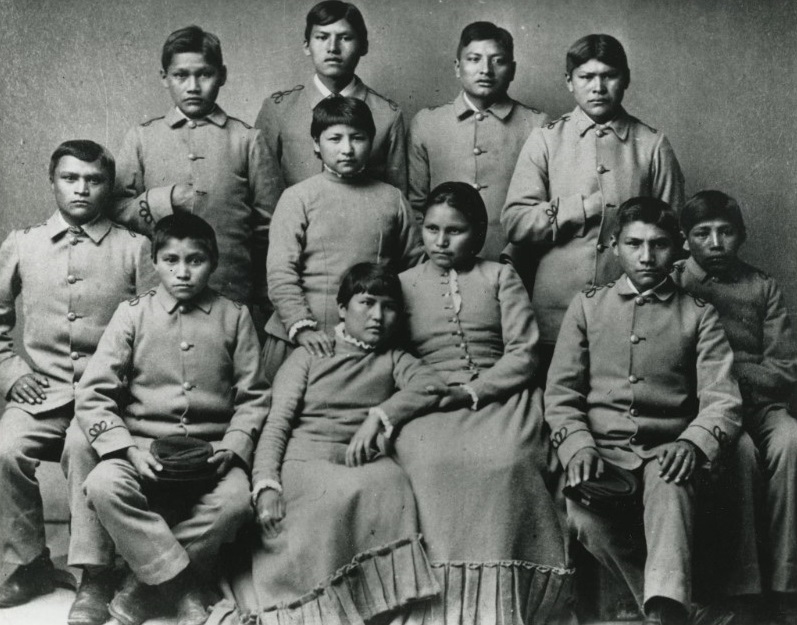

[Photo above: Sioux children are seen before entering Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1897. Native American children — some as young as 5 — were forcibly removed from their homes and sent hundreds of miles to Indian boarding schools. (Library of Congress)]

The hidden legacy of the Indian boarding schools in the United States

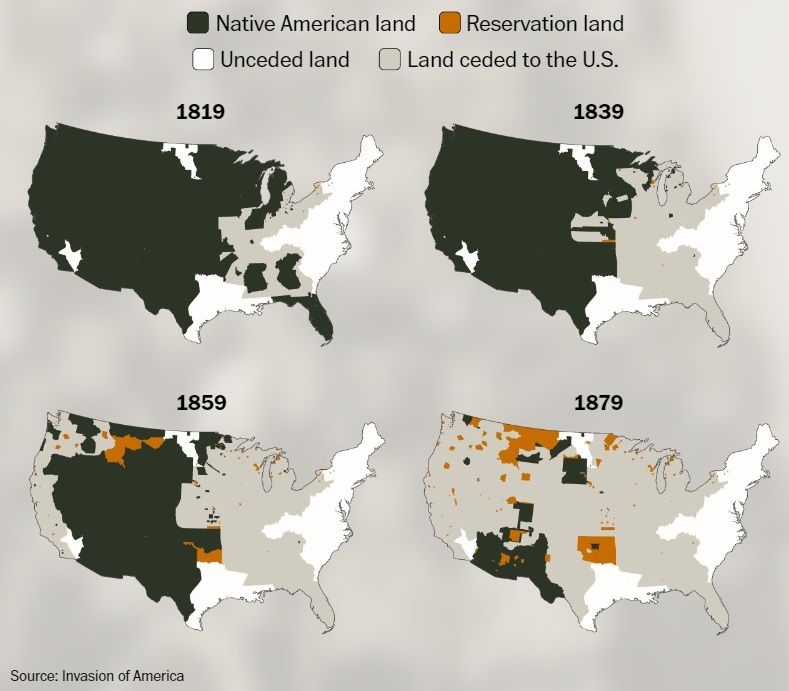

From 1819 to 1969, the U.S. government separated Native American children from their families to eradicate their cultures, assimilate them into White society and seize tribal land.

1. European settlers waged war against Native Americans for centuries, decimating tribes through violence and spreading disease. By the 1800s, the U.S. government continued to grapple with what it called the “Indian problem.”

American settlers embraced Manifest Destiny — the belief that they had a divine right to seize all of North America. But the Native Americans already inhabiting the land stood in their way. Historians note that pre-Columbus there were several million people in what’s now North America who spoke more than 300 languages. By the start of the 20th century, there were about 200,000 Native Americans left in the United States, and they had lost control of roughly 1 billion acres of land.

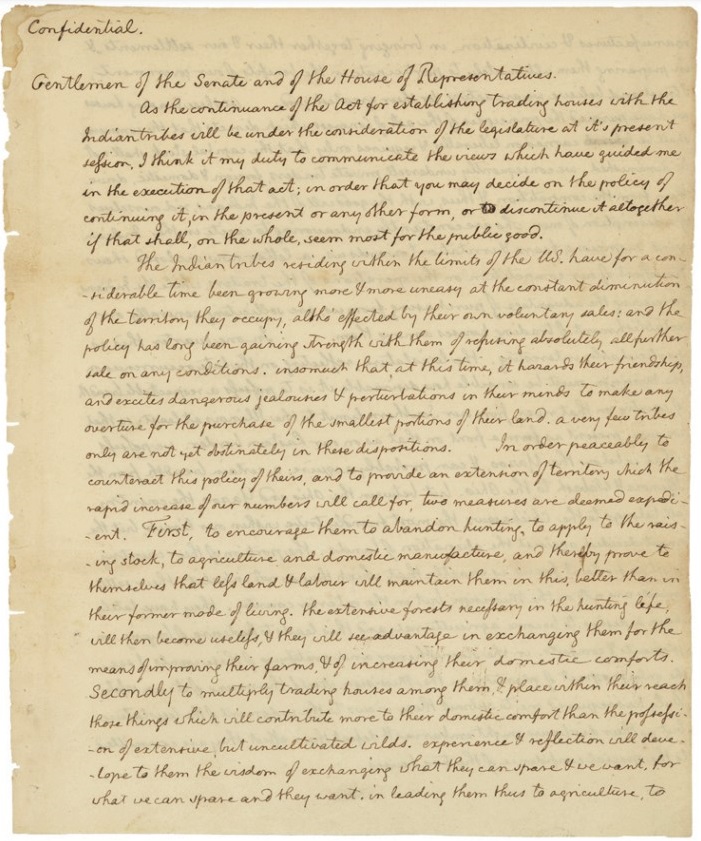

George Washington believed that forcing Native Americans to assimilate to White culture would reduce bloodshed and expand the new country’s territory. He wrote a letter to a member of the New York state Senate in 1783, six years before he became the first president of the United States:

“The gradual extension of our Settlements will as certainly cause the Savage as the Wolf to retire; both being beasts of prey tho’ they differ in shape.”— George Washington

The Declaration of Independence, whose primary author was Thomas Jefferson, referred to Native Americans as “merciless Indian Savages.” As the nation’s third president, Jefferson sought to persuade Native Americans to abandon their way of life and, by extension, their land. “Encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture … the extensive forests necessary in the hunting life, will then become useless, & they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms, & of increasing their domestic comforts,” he wrote in a message to Congress in 1803.

Jefferson also wanted to force Native Americans into debt so they would sell their land. In an 1803 letter to William Henry Harrison, who governed what was then the Indiana territory, he wrote:

“We shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good & influential individuals among them run in debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop [them off] by a cession of lands.”— Thomas Jefferson

2. The government wanted tribal land for settlers and needed to justify taking it. If Native Americans adopted Western ways of education and farming, officials said, they would need less land.

For the U.S. government, forcing a Western education on Native American children was the pathway to what officials called “civilization.” Between 1778 and 1871, some tribes, often after being coerced by the U.S. government, signed more than 300 treaties that promised access to education, hunting and fishing rights, housing, or health care in exchange for their lands.

As the government’s policy shifted from war to assimilation, officials spoke about Native Americans more as inferior dependents than as dangerous enemies. “With the Indian tribes it is our duty to cultivate friendly relations and to act with kindness and liberality in all our transactions. Equally proper is it to persevere in our efforts to extend to them the advantages of civilization,” President James Monroe said in his 1817 inaugural address.

In a letter that same year to Andrew Jackson, then an Army general, Monroe said, “Nothing is more certain, than, if the Indian tribes do not abandon that [hunter or savage] state, and become civilized, that they will decline, and become extinct.”— James Monroe

Two years later, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act, which provided $10,000 annually for the president to “employ capable persons of good moral character to instruct [Native Americans] in the mode of agriculture suited to their situation; and for teaching their children in reading, writing and arithmetic.”

Education, officials realized, would also save the government money. In his 1881 essay “Present Aspects of the Indian Problem,” former Interior Secretary Carl Schurz said: “We are told that it costs little less than a million of dollars to kill an Indian in war. It costs about one hundred and fifty dollars a year to educate one.” He concluded that investing in establishing more boarding schools was not only “a philanthropic act, but also the truest and wisest economy.”

Native Americans were forced off their land by the Indian Removal Act, which was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by Jackson, who had been elected president in 1828. The law began the mandated removal of thousands of Native Americans in what is known as the Trail of Tears. Two decades later, the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 created reservations and pushed Native Americans into increasingly smaller spaces.

Jackson said in his 1833 annual address to Congress:

“They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition … they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”— Andrew Jackson

3. As Native Americans were forced off their land and onto reservations, the government established day schools for their children. But U.S. leaders concluded they needed to be more aggressive to fully eradicate their cultures.

“The idea was to transform Indian children so they’d have a different set of values,” said Brenda Child, a Native American historian who is Red Lake Ojibwe and whose grandparents were sent to Indian boarding schools. “They’d speak English, be Americanized and not live as their grandparents.”

But since children still lived with their families, officials were concerned that their cultures and languages persisted.

Carl Schurz, the U.S. interior secretary at the time, wrote in 1879:“It is the experience of the department that mere day-schools, however well conducted, do not withdraw the children sufficiently from the influences, habits, and traditions of their home-life, and produce for this reason but a comparatively limited effect.”— Carl Schurz

An 1886 annual report from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs drew a similar conclusion: “Only by complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents can he be satisfactorily educated.”

4. U.S. officials ordered Native American children to be removed from their homes and sent to remote boarding schools. As one of the first boarding school founders said, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

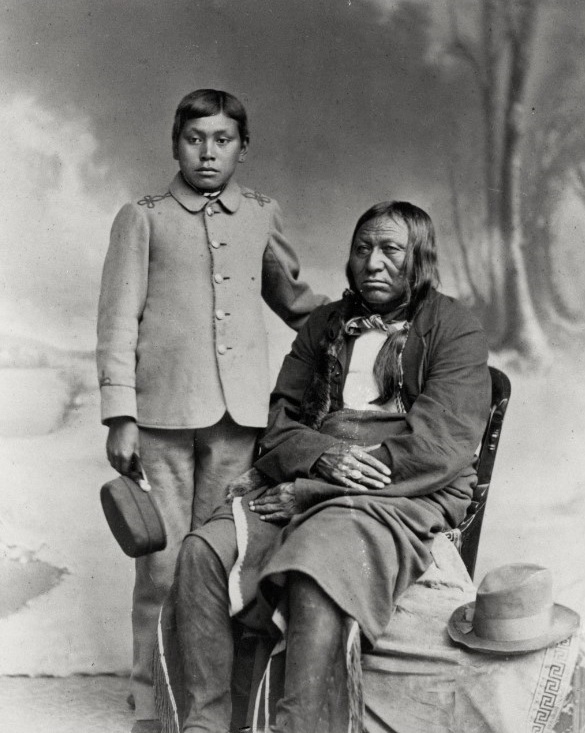

In 1879, the first government-run boarding school located off a reservation opened its doors. Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded by U.S. Army Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt, a Civil War veteran who had fought Native Americans on the Western frontier. Among the first students at Carlisle were the children of Apache prisoners of war who had been captured after their leader Geronimo surrendered to U.S. forces.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Pratt said in an 1892 speech delivered at the National Conference of Charities and Correction. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Jim Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox Nation who later became the first Native American to win an Olympic gold medal for the United States, attended Carlisle in the early 1900s.

Carlisle, and Pratt’s philosophy, became the model for hundreds of other boarding schools that eventually opened across the country. Oklahoma had 95 Indian boarding schools, the most of any state.

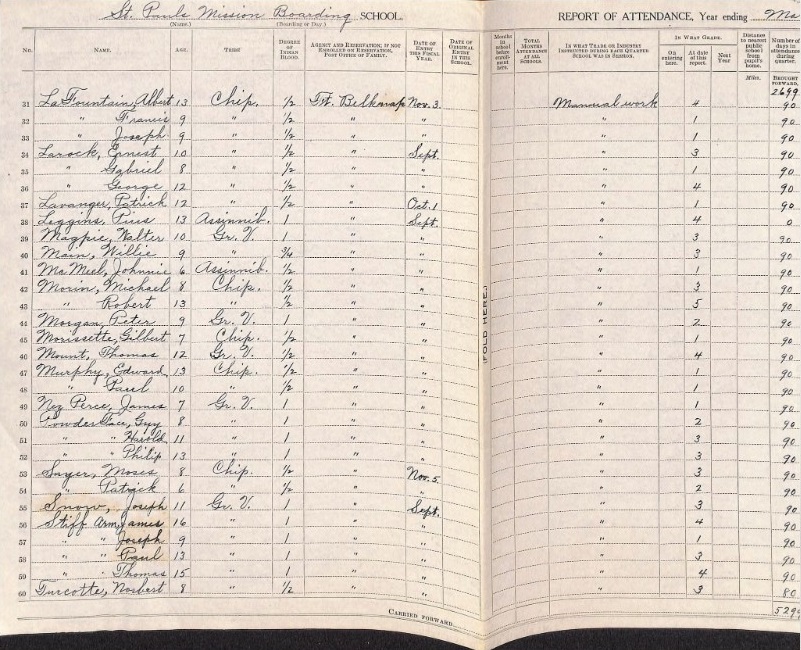

The children were banned from speaking any language but English. They were forced to abandon their customs, dress in Western clothing — some in military-style uniforms — and convert to Christianity. Former students recall arriving at school and being sprayed with DDT, whether or not they had lice. Often, children from the same tribe — and even the same family — were split up in an attempt to sever familial bonds. Attendance lists marked children’s “degree of Indian blood” as half or one, meaning half or full.

School and government officials viewed Native Americans’ long hair as a sign of their savageness and cut it off, traumatizing children raised to believe their hair was a source of pride and cultural identity. In a 1902 letter, Commissioner of Indian Affairs William A. Jones wrote that “the wearing of short hair by the males will be a great step in advance and will certainly hasten their progress towards civilization.” He warned that if young men did not keep their hair short after they returned from school, there would be consequences from local officials at home. “Employment, supplies, etc., should be withdrawn until they do comply and if they become obstreperous about the matter a short confinement in the guard-house at hard labor, with shorn hair, should furnish a cure.”

Luther Standing Bear, an Oglala Lakota, spent six years at Carlisle Indian Industrial School starting in 1879. He said: “We were to be transformed, and short hair being the mark of gentility with the white man, he put upon us the mark.”

5. At least 523 Indian boarding schools were established in the United States. Religious groups received federal contracts to operate about a third of them. Families were often coerced by federal agents or priests to send their children.

The government hired missionary groups and churches from Christian denominations including Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, Presbyterian and others to run the schools. The Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers, also ran about 30 schools. The government paid the schools about $167 per year for each child in attendance, according to an 1886 report to the Interior Department.

The financing of the boarding school system added to the devastation wrought on Native American communities. According to a 1969 Congressional report, “proceeds from the destruction of the Indian land base were to be used to pay the costs of taking Indian children from their homes and placing them in Federal boarding schools.” Land was taken from Native Americans and sold, and those funds were then used to cover the cost of the Indian boarding school system.

Congress passed a law in 1891 authorizing the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to “make and enforce” rules that would secure the attendance of children at the new schools. And more children in the schools meant more money for the people running them.

Federal agents searched homes for children and dragged them out, according to Willard Beatty, director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs education program from 1936 to 1951.

Beatty later wrote about a conversation with Clyde Blair, the former superintendent of Albuquerque Indian School. In a 1961 essay, Beatty wrote of how decades earlier Blair told him how he was involved in “recruiting” Navajo students for his school under “orders from Congress.” If children resisted, Blair told Beatty, they “wrestled them to the ground, tied their legs and their arms,” and put the children in the back of the wagon until they had “gathered in the quota for the day.”

George Horse Capture Jr. of the Aaniiih (Gros Ventre) tribe on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation told Washington Post reporters last summer how his ancestors were required to go to the schools, a story that has been passed down through his family:

“They picked up one of my great greats … and her grandma was hanging on to the edge of the wagon, pleading, pleading. And one of them soldiers hit her in the fingers with the butt of his rifle to get her off the wagon.”— George Horse Capture Jr.

To force attendance, Congress passed a law in 1893 allowing government officials to withhold food rations from families who refused to send their children to school.

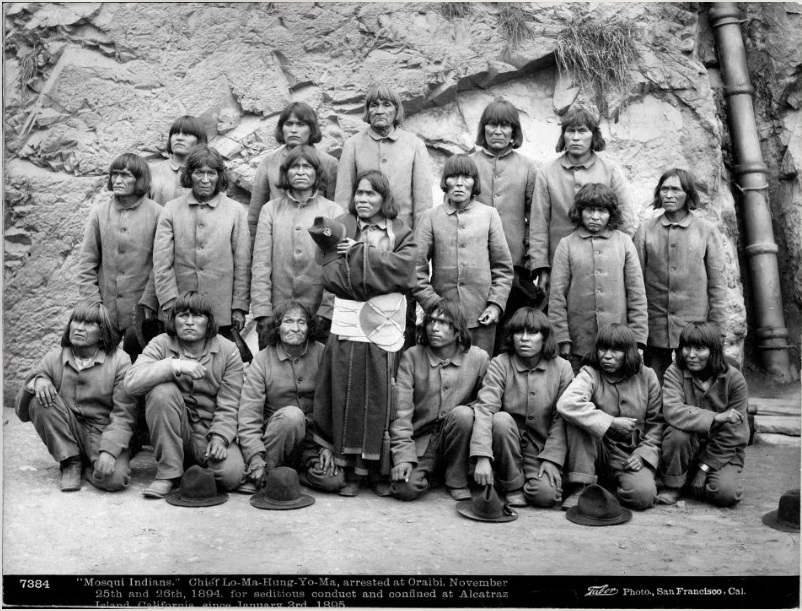

Some parents still resisted. In 1894, a group of Hopi parents refused to send their children to the Keams Canyon Boarding School in the Arizona territory. Federal troops were called in, and they arrested 19 Hopi leaders, who were then imprisoned at Alcatraz Island for nearly a year.

6. Physical abuse, disease and malnutrition were widespread in the schools. Many children were sexually abused by the priests, sisters or other members of religious orders charged with their care.

Overcrowding, poor diets and little medical care often meant that tuberculosis, measles and other diseases spread quickly. Children went hungry. They were coerced to work for families in surrounding communities.

Their education was minimal, according to government reports. Children spent half of the day learning basic arithmetic, reading and writing, and the rest of the day working — farming and vocational work for boys; laundry, sewing and cooking for girls.

Corporal punishment was supposed to be allowed only in cases of “grave violations of rules.” It was to be done or supervised by the superintendent, according to the 1890 report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. But former boarding school students say these limits on punishment were rarely enforced, especially at remote schools.

“It really was a poor school,” said Thresa Lamebull, who was born around 1907 and went to St. Paul Mission and Boarding School in Hays, Mont., as a child. Her interview appeared in a 1982 book, “Recollections of Fort Belknap’s Past.”

“We hardly had anything to eat. … The Ursuline nuns they were really strict. They would punish us and whip us, if they heard us talk our language.”— Thresa Lamebull

Runaways faced beatings or solitary confinement. Many boarding school survivors recalled a common punishment: the “belt line.” A student who’d done wrong would be forced to strip to their underwear and then had to run down a line of classmates who hit them with hot, wet towels that had sharp pins on them.

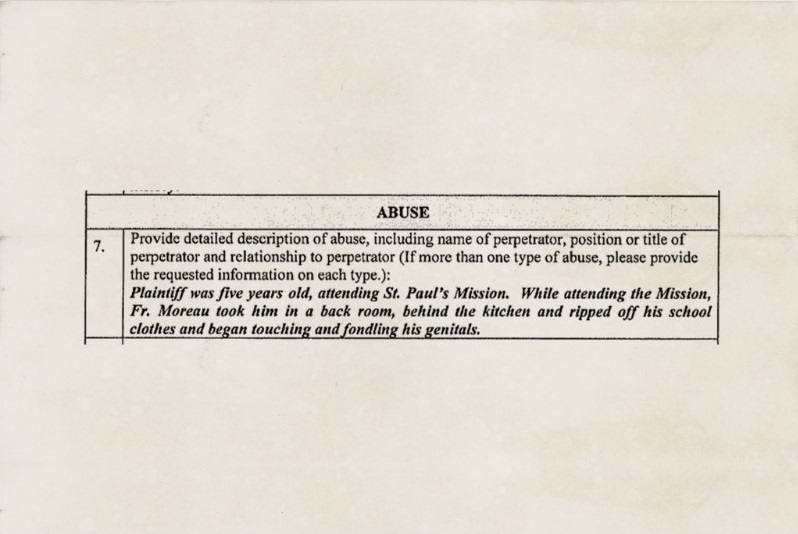

In addition to the physical mistreatment, children suffered sexual abuse by priests, sisters or the members of religious orders who ran many of the schools.

An examination by The Post found that since the 1890s, at least 122 priests, sisters and brothers who were later accused of sexually abusing children under their care worked at 22 Indian boarding schools. Most of the abuse documented as part of this investigation occurred in the 1950s and 1960s and involved more than 1,000 children. Experts say The Post’s findings are a window into the widespread sexual abuse at Indian boarding schools. But the extent of the abuse was probably far worse, because the lists of accused priests are inconsistent and incomplete, and many survivors have not come forward. Others are aging and in poor health, or, like their abusers, have died.

7. An unknown number of children died at the Indian boarding schools. Many of them were buried in unmarked graves.

The Interior Department estimated in 2022 that at least 500 children died while at boarding schools, but it said the number could climb to “the thousands or tens of thousands” as its investigation continues.

Parents were often prohibited from visiting the schools. Sometimes, they found out that their children had become ill and died after they’d already been buried at cemeteries on the school’s grounds. By 1891, the Spokane Tribe of Indians in Washington state sent 21 children to boarding schools. Sixteen died, according to Chief Lot, a Spokane chief, who said in an 1891 speech:

“My people … do not want to send their children so far away to school. If I had had their children (the white people’s children) I would have put their bodies in a coffin and sent them home, so that they could see them. I don’t know who did this, but they treated my people as though they were dogs.”— Chief Lot

8. After two critical government reports, most of the Indian boarding schools closed. By then, generations of Native Americans had attended. Many children and their families were left deeply scarred.

By 1900, 1 in 5 Native American school-age children attended a boarding school. The U.S. government ran and promoted the schools for decades even as its own reports documented and warned of growing problems.

In 1928, the federal government commissioned Lewis Meriam of the Institute for Government Research, now the Brookings Institution, to report on the schools. The report found that “provisions for the care of Indian children [were] … grossly inadequate.” Noting that “the effort has been made to feed the children on a per capita of 11 cents per day,” the report found that many of the children were “below normal health.”

Children as young as 10 spent four hours a day doing “heavy industrial work,” which the report said would “constitute a violation of child labor laws in most states.” The report noted that discipline was “restrictive,” but it made no mention of sexual abuse.

“On the whole government practices may be said to have operated against the development of wholesome family life,” the report said.

Decades later, a 1969 congressional study, by the Senate Special Subcommittee on Indian Education that was chaired by Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), delivered a searing criticism of the schools — though it did not mention sexual abuse. “They were designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people,” said the report, titled “Indian Education: A National Tragedy — A National Challenge.”

The report said, “Herein lies the most serious deficiency of the entire boarding school system, for these people are in charge of the children 16 hours a day, 7 days a week, yet they are understaffed, [underprogrammed], undersupervised and overextended.”

Children were academically three years below their grade level, and they cried themselves to sleep at night for weeks upon arriving. The report concluded: “At best the schools are totally unsatisfactory as a substitute for parents and family. At worst they are cruel and barbaric.”

Following the report, which made 60 recommendations to overhaul education, the federal government closed down many of the Indian boarding schools.

9. Today, there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, and their cultures endure. Native American groups still want an apology for the Indian boarding schools from the president and the pope.

There has been no formal apology from any U.S. president for the mistreatment of Native Americans at boarding schools. In 2010, deep within the Defense Appropriations Act, there was an apology “on behalf of the people of the United States to all Native Peoples for the many instances of violence, maltreatment, and neglect inflicted on Native Peoples by citizens of the United States.” The act was signed by President Barack Obama; however, it made no mention of boarding schools.

According to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, less than a quarter of the schools remain open today and are very different from the original boarding schools. The schools are now run by tribes or by the federal government’s Bureau of Indian Education. They teach and promote Native American culture and languages, and families can choose whether their children attend.

In 2022, the U.S. Interior Department — led by Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary — released its first report on the 150-year period of Indian boarding schools. It concluded that the United States “established this system as part of a broader objective to dispossess Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Villages and the Native Hawaiian Community of their territories to support the expansion of the United States.”

In Canada, the U.S. boarding schools were an “inspiration,” according to a Canadian report, for a similar, much smaller network of schools. There, the government has taken steps to account for the abuse and neglect, apologized and paid billions in compensation. In 2022, Pope Francis apologized for the role of the Catholic Church in the Canadian schools.

Advocates want to see a similar reckoning in the United States.

Deborah Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said:

“We want to know what happened to our grandmothers, our parents, our family members. We’ve been lied to. We want to know the truth. We need to begin to heal.””— Deborah Parker

About this story

First photo: Sioux children are seen before entering Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1897. Native American children — some as young as 5 — were forcibly removed from their homes and sent hundreds of miles to Indian boarding schools. (Library of Congress)

This story is part of a series examining the legacy of America’s network of Indian boarding schools. Do you have a tip or story idea for our investigation? Email our team at boardingschools@washpost.com.

Reporting by Dana Hedgpeth and Sari Horwitz.

Additional reporting by Emmanuel Martinez and Nate Jones.

Design by Natalie Vineberg. Development by Jake Crump. Graphics by Janice Kai Chen. Video by Alice Li.

Editing by Jenna Pirog, Sarah Childress, David S. Fallis and Wendy Galietta. Additional editing by Jay Wang and Courtney Kan.

Design editing by Madison Walls. Photo editing by Robert Miller and Troy Witcher. Graphic editing by Emily M. Eng. Video editing by Nicki DeMarco.

Additional support from Cameron Barr, Kathy Baird, Matthew Callahan, Brandon Carter, Matt Clough, Maddie Driggers, Salwan Georges, Stephanie Hays, Scott Higham, Angela Hill, Jeff Leen, Jenna Lief, Jordan Melendrez, Martha Murdock, Sarah Murray, Amy Nakamura, Kyley Schultz, Erica Snow and Peter Wallsten.

Sources

“Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928,” David Wallace Adams.

“Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences,” edited and with an introduction by Clifford E. Trafzer, Jean A. Keller and Lorene Sisquoc.

“Boarding Schools Seasons: American Indian Families 1900-1940,” Brenda J. Child.

“American Indian Education: A History,” second edition, Jon Reyhner and Jeanne Eder.

“The Spokane Indians: Children of the Sun,” Robert H. Ruby and John A. Brown.

“American Indian Children at School 1850-1930,” Michael C. Coleman.

“Recollections of Fort Belknap’s Past,” Morris “Davy” Belgard, 1982.

U.S. Department of the Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative — Investigative Report, 2022.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

“Away From Home: American Indian Boarding Schools Stories,” The Heard Museum, Phoenix.

“The Old Chief’s Appeal: Eloquent and Convincing Address by the Venerable Chief of the Spokanes,” Spokane (Wash.) Daily Chronicle, Oct. 12, 1891.