MEXICO CITY (MEXICO)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

September 23, 2024

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

From Mexico, to Argentina, and then to Germany: clergy sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church links these three, different countries.

In Mexico and Brazil, predator priests with less than ten years of service, dominate the scene; in Mexico, the U.N. calls for a national commission to address clergy sexual abuse.

In Argentina, a key week for survivors of clergy sexual abuse starts today as two cases go to the courts, while in Germany a women’s group seek major changes at the incoming Synod at Rome.

Last week, media in Mexico City told once again the story of a young priest accused of clergy sexual abuse by one of his victims.

Below this paragraph, a short story broadcast by a local news channel in Mexico City provides some details about the allegations.

A story from a Mexican newscast. Audio available only in Spanish.

At this point it is impossible to know the details of the abuse. It is unknown if it was only an attempt or if Jacinto Jiménez Tepetlixpa actually attacked his victim. It is known, however, that the attack happened at the foundation presided by the priest, and that the victim was not a minor.

However, it is possible to set this new case as part of a trend in Latin America. Unlike what one sees in France, Canada, or the Unted States, where the cases are old instances of this phenomenon, in Mexico and other countries of Latin America, there are new cases whose main characters are priests newly minted in the region’s seminaries.

A few weeks ago, Los Ángeles Press told the story of Paulo Araújo, a young priest from the diocese of Coari, at the heart of the Brazilian Amazons, arrested by the local police at the curial house of the parish he was serving as pastor.

English Edition

The crime of Father Araújo

He was there with the most recent of a string of young females with whom he has had some type of relation. One of them was, back in September of 2023, an underage teenager who got pregnant. Araújo forced into an abortion. A friend allowed Araújo to bury the corpse of the fetus in his orchard.

New generation, old vices

Before that, we ran a story, linked after this paragraph, about a new priest, ordained in the first decade of this century who, before his ordination abused at least one homeless kid from the streets of Quito, Ecuador.

Years later, in March of this year to be precise, that former homeless kid, decided to hang himself in the rooftop of the Ecuadoran Congress after unsuccessfully attempting to achieve some measure of justice from the diocese of Galápagos.

English Edition

Suicide at the Congress

Back in January, Los Ángeles Press ran a couple of short series, available only in Spanish, about priests serving the archdiocese of Mexico City and the diocese of Izcalli, both in the larger metropolitan area of the Mexican capital.

México violento

Cómo fue la liberación del cura acusado de abuso sexual en Tlalpan

Sergio González Guerrero, the priest working at the archdiocese of Mexico City and Morseo Miramón Santiago, the priest from the diocese of Izcalli are young, newly minted, priests who despite the many promises of the global Roman Catholic hierarchy in the last 40 years or so attacked underaged male kids. If you read Spanish, you can find the first installment of each of those series linked before and after this paragraph.

México violento

Sacerdote de Izcalli, acusado de abuso de un niño de 11 años

The new case in Mexico City is consistent with these new crop of clergy abusers. The Roman Catholic Church seems to be unable to learn lessons from the failures of the 2005-7 reform of Benedict XVI, and the ongoing reform process launched by Pope Francis.

Jacinto, as Sergio, Morseo, and their Brazilian colleague Paulo entered the seminary after the reforms of both Benedict XVI and Francis. Even Franklin Germán, became a priest in Ecuador after Pope Joseph Ratzinger’s reforms.,

Morseo became a priest in 2017, Paulo in 2018, Sergio in 2020, and Jacinto in 2021. So, there is no way to claim that they or their superiors were not aware of the need to address the clergy sexual abuse crisis.

It is actually possible that Morseo and Sergio ordinations occurred because the diocese of Izcalli and the archdiocese of Mexico were willing to bend the new rules to allow for their ordination, despite the accidented paths they followed.

A fragment of Jacinto’s ordination mass at the Basilica of Guadalupe. The bishop asks the Trinitarian order if Jacinto is worthy of ordination.

With Jacinto as with Paul Araújo there is no evidence of rule bending, but there is no evidence on the contrary, and given the outcomes, it is up for the reader to figure out if it is possible to trust Jacinto’s superiors at his order or the bishop of Coari, Brazil, as far as Araújo is concerned.

Jacinto is a member of one of the oldest religious orders in the Roman Catholic Church. French priests Jean de Matha and Felix de Valois founded the Order of the Most Holy Trinity and of the Captives, for short Trinitarians, in 1285.

But they are a new arrival to Mexico. That is why, unlike other small orders placing their works in Mexico under the provinces of other Latin American or the United States, this order’s works in Mexico are under the authority of the Italian province.

Journey to Italy

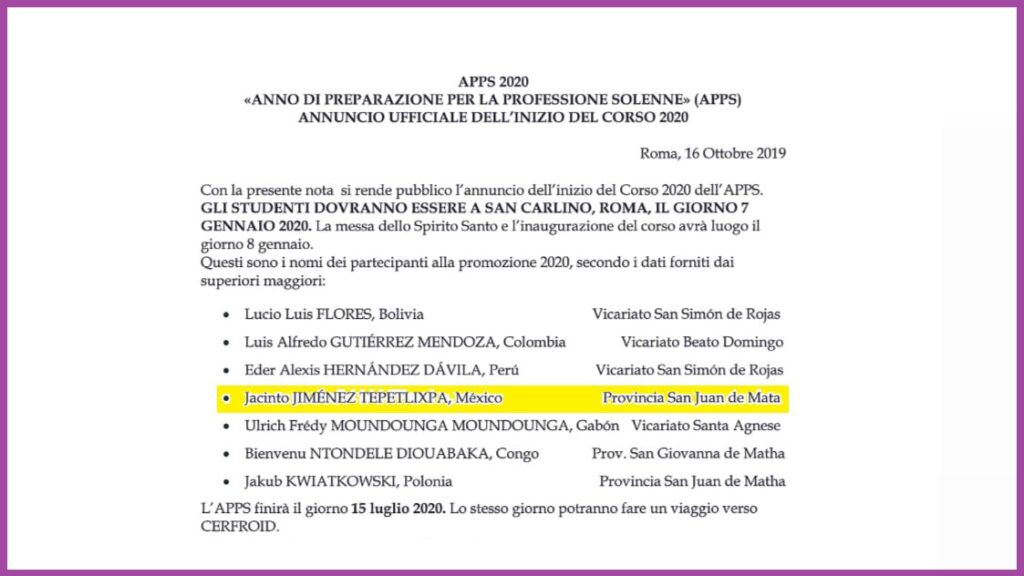

As such, Jacinto, spent some time in Italy. It was there, where he made his full profession as member (brother or friar) of the order, back in January 2019, with novices from all over the world, as his order tells, in Italian, in the message appearing as an image after this paragraph, taken from a magazine published by the order.

It was also there, in Livorno, Italy, where bishop Simone Giusti presided the ceremony where he ordained Jacinto as a deacon on October 4th, 2020, as the image appearing after this paragraph summarizes.

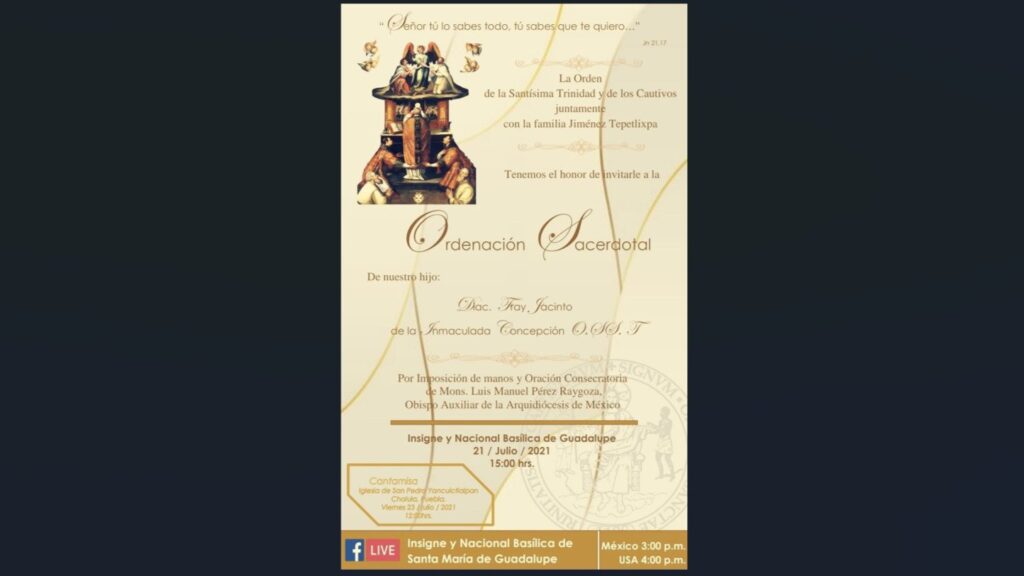

Little less than a year after, on July 21st, 2021, at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, Luis Manuel Pérez Raygoza, auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Mexico, ordained Jacinto, as the invitation that appears after this paragraph summarizes in Spanish.

A Facebook profile that identifies itself as the community of San Pedro Yancuitlalpan, in the state of Puebla, where relatives of Jacinto Jiménez Tepetlixpa live, on July 21, 2021, and was available until September 22nd 2024 here, published the invitation while expressing pride that one person with ties with that community was about to be ordained at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe

San Pedro belongs to the municipality of San Nicolás de los Ranchos, a community on the slopes of the Popocatepetl volcano, ten miles or 16 kilometers East of the summit of that mountain and 17 miles or 28 kilometers West of Puebla.

The pride from the people in the old town, where his relatives live and where Jacinto went back to celebrate his first mass, the so-called Cantamessa, is legitimate and understandable. What is harder to understand is how the bishops and superiors at religious orders appoint their priests to key positions

[PHOTO: A nun leads the congregation’s prayers during Jacinto’s first mass in San Pedro.]

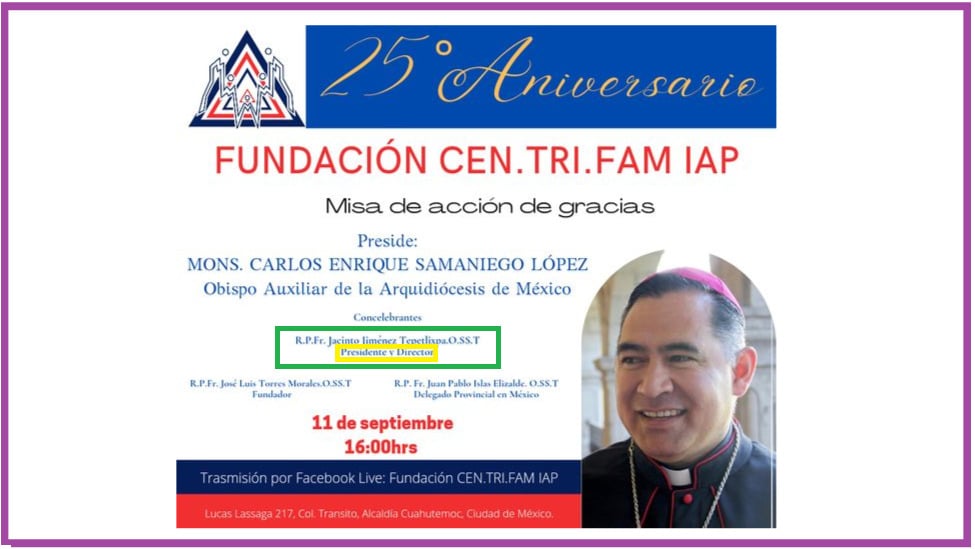

As it happened with Paul Araújo in Coari, after his ordination the Trinitarian order appointed Jacinto as the top authority of their most significant work in Mexico City, a foundation devoted to providing food and refuge to homeless people in the Mexican capital.

Even if he was trained to deal with the everyday operations of a foundation, it is unavoidable to ask if he was emotionally mature and ready to be the top authority in that foundation, as the image appearing after this paragraph, published in the early days of December 2021, describes the situation, Jacinto was the chairman of the board (presidente) and general director of that foundation.

The shadow of Abbé Pierre

Was he ready to negotiate his own role in the lives of severely marginalized homeless persons in Mexico City? Was his order aware of the kind of responsibility they were conferring on a young, inexperienced priest? What was the decision-making process leading to the concentration of so much authority on his hands?

Readers must keep in mind, in this respect, the story of Abbé Pierre, a hero of the French Resistance in second World War whose story is relevant because he was also the sole authority of Emmaus, the non-for-profit created by Pierre himself in the mid-20th century, when France was hit by an extreme cold wave. The story appears after this paragraph.

Even in Marcial Maciel’s and many other cases, one key trait, is how priests with some unresolved affective issue concentrate authority, responsibility, and power in non-for-profit organizations. See, as one of many examples the case of Argentine priest Julio César Grassi, one of the seven cases included in the story linked below.

English Edition

Seven stories of clergy sexual abuse

The picture after this paragraph, published in early December 2021 describes Jacinto as chairman of the board and general director of that foundation.

The official information that the foundation sends to the authorities in México City confirms Jacinto’s position as top leader there. The box after this paragraph displays a pdf file of the non-for-profit registration with the relevant authority in Mexico City and it is available only in Spanish.

https://losangelespress.org/view-pdf/?url=/__export/sites/lapress/pdfs/2024/09/22/FbszRgk9UiQcjSXa.pdf

Jacinto does not appear there with his ecclesiastical titles, but he appears as patrono presidente, that could be translated as “chairman of the patrons”. It is hard to believe that he could have achieved such position if he was not a priest.

As in the case of Paulo Araújo’s appointment as pastor of a parish, what was the process leading to Jacinto’s appointment to that position in Mexico City? As in the case of Franklin Germán Cadena Puratambi and the Salesian order in Quito, or Grassi in Argentina, who evaluates these appointments of the religious personnel dealing with marginalized populations in Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, or Argentina?

In Cadena Puratambi’s and Grassi’s cases it would be possible to assume that back in the 1980s (Cadena Puratambi) or 1990s (Grassi), when they perpetrated their attacks, there was little systematic knowledge about the potential effects of vesting so much power on rookie clerics, but Jacinto’s case in Mexico City or Araújo’s in Coari, Brazil, are emerging after 40 years of negative experiences with this type of appointments for positions that require something more than enthusiasm.

And Jacinto, as Grassi used to do 30 years ago in Argentina, during the Carlos Saúl Menem administration, was very willing to play the part, and to pose for pictures published over the foundation’s Facebook profile to prove how close he was to the homeless and marginalized in Mexico City. One of said pictures appears before this paragraph.

That is what one finds in the pictures that the Facebook page of the Foundation Cen-Tri-Fam (Centro Trinitario Familiar in Spanish or Family Trinitarian Center) used to publish until last week when news broke about the accusation against Jacinto.

That the foundation is relevant for the order can be seen in the fact that two months ago, back in July, two global leaders of the Trinitarian order were there, Father Luigi Bucarrello and Father Antonio A. Fernández, as the image before this paragraph proves.

The picture before this paragraph has Jacinto standing and looking at Father Fernández while he signs the Distinguished Visitors book at the foundation.

The next picture has Father Bucarrello presiding over mass at the chapel in the foundation building.

It is hard to know how Jacinto’s order, the Trinitarians, will respond to this crisis. And even harder to figure out the way the Archdiocese of Mexico will deal with it. Even if he was not a pastor in a parish at the archdiocese, he was celebrating masses in Cardinal Carlos Aguiar Retes’s territory, so he had some ecclesiastical licenses to do so.

Eventually, Aguiar will be involved on this matter, as he will be if and when some measure of justice is offered to the victim of Sergio González Guerrero. If not, the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico will just prove, once again, how dismissive are its leaders when dealing with the lives of their own faithful.

If something has been learnt after 40 years of clergy sexual abuse crisis is that it is the very Roman Catholic Church the most affected by the dismissiveness of the bishops on this issue. One only needs to go back to the story told last week here, about the Peruvian priest from Chiclayo, Eleuterio Vázquez Gonzáles, linked after this paragraph, to see how his victims were among the most faithful, the most loyal families in his parish.

English Edition

From Chicago to Chiclayo, sexual abuse victims are pawns

However, Cardinal Aguiar Retes, as the rest of the Mexican Roman Catholic bishops must be aware by now that back on September 16th, the very day of Mexican independence, the Committee on the Rights of the Child of the United Nations published the advanced unedited version of its combined sixth and seventh reports on Mexico.

There, as it has been already the case before, the Roman Catholic Church is specifically named for its role in what the document calls “Sexual abuse by religious personnel of the Catholic Church” (p.7). It goes to call for setting up…

«…a formal State-led independent inquiry into child sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, with full power of investigation, with a view to identifying the failures of the State institutions, identifying the victims, including of past abuses, and establishing a mechanism to compensate them. »

Even if it is hard to believe that the current or the incoming government would accept the suggestion of the Committee the risk of an increased politicization of the issue is there and the many contradictions in the behavior of the Mexican Conference of Bishops and the resentment that their attitude towards the victims and their families bring about is the worst imaginable combination.

More so for a Church that also faces serious demographic challenges from an increasingly older base, and the constant, seemingly unstoppable growth of the nones, that is to say the people declaring themselves as having no religious affiliation in the Mexican national census that, unlike that of the U.S. has a specific question for religious affiliation.

The full document from the United Nations is available here.

An Argentine milestone

A litte less than a month from today, on October 21st, Argentina will have, for the first time in the history of the clergy sexual abuse crisis there two priests on trial.

The crisis has been bad there and it would be relevant to have this coincidence in their trials even if Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the former archbishop of Buenos Aires was not, as he is, the top leader of that church.

The cases are that of Carlos Fernando Páez, to be on trial in Tartagal, province of Salta, in the Argentine Northwest. The other deals with the abuse perpetrated by Daniel Amado Martín Bustamante, at Lomas de Zamora, a municipality in the Province of Buenos Aires, close to the national capital, the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and half-way between that city and that of La Plata, as the map above shows.

More than 840 miles or 1,350 kilometers separate the court houses where the trials will happen, and deal with two different cases, and they confirm that the issue is not only gay clergy sexual abuse, but clergy sexual abuse at large.

The State’s attorney at Salta had requested a trial for Páez since May 2022, but as it is usually the case in Latin America, judges do not rule on these requests as soon as it would be required, so it will be next month when Páez will face the charges.

He abused a now former seminarian when he was the pastor of Santa Cruz at Villa Saavedra de Tartagal, 38 miles or 60 kilometers South of the border with Bolivia, as the map above shows.

A summary of the State’s Attorney request is available, only in Spanish here.

Although the State’s Attorney fought hard to keep the victim’s identity reserved, Kevin Montes, the former seminarian, was willing to share his testimony with Argentine media. If you read Spanish, an account of his experience with abuse is available here.

Another account is available here, when it was expected that the trial was about to begin, back in April 2023.

One key element of Montes’s testimony is that he stresses how Páez’s abuse was not new back when he suffered the abuse, from 2015 through 2017.

According to Montes’s account, Páez has been abusing, even underaged males at the premises of the parishes where he has served, since 1998. Montes stresses also that many of Páez’s victims are unwilling to offer a testimony.

One more female victim

A difference between Páez’s and Daniel Amado Martín Bustamante’s case is that a young female accuses the latter of raping her. The victim reported him back in March of this year, although it is unclear if the abuse happened when the victim was already eighteen or before, what is known is that the victim was under Martín Bustamante’s pastoral care.

The priest went as far as to surrender to the authorities and although first he declined the chance to make an statement, later he rendered the situation as a “love affair” (relación amorosa), and not as abuse as this story printed by local media tells.

As it is frequent in Latin America, the Argentine authorities dealing with the case in Lomas de Zamora have been unwilling to probe if there are other accusations against the priest.

He was separated from his duties by the diocese of Lomas de Zamora but they keep him a priest, as the image below proves, a screenshot of the diocese’s website available, until Sunday September 22nd, here .

Finally, as far as Argentina is concerned, tomorrow Tuesday an appeals court will decide whether to dismiss or accept an accusation against Raúl Eduardo López Márquez. The reason is that the abuse happened between 1997 and 2001 in Chumbicha, Catamarca, so the cases have expired.

However, other accusation against the same priest is already at trial, so there is a chance that the defense claim could be dismissed by the appeals court, opening the door for other victims in an analogous situation.

From Germany, with love

In Germany, the sexual abuse crisis has been about to force out at least two Cardinals from their sees. It was the case with Reinhard Marx, archbishop of Munich and with Reiner Maria Woelki, archbishop of Köln. Despite their attempts at ending their tenures, Rome keep them in their positions.

However, there is a deep crisis. Given the nature of the Church-State relation and the Tax Code there are ways to measure the anger affecting the Roman Catholic base, tired of the endless stream of predator and/or abusive priests contradicting with their action their stern interpretation of Roman Catholic sexual morality, when it is about other people, while when it is about priests, they are willing to dismiss any transgression.

As a consequence, Germany has been the epicenter of a very active movement to offer an alternative to Rome’s understanding of sexual morality and, above all, practical and effective ways to end the clergy sexual abuse crisis.

However, the German groups of laypersons doing this are nowadays frequent targets of attacks from bishops and other leading figures in the English- and Spanish-speaking Roman Catholic worlds dismissing their critique of the situation. They also repudiate their stated goal of changing the rules on priestly celibacy, and the rules setting the females as permanently excluded from ordination.

In the coming weeks, the German laypersons led by organizations as Maria 2.0, the Katholischer Deutscher Frauenbund (KDFB for Catholic German Women’s Association), and Wir Sind Kirche (We are Church), will do their best to influence their own bishops and bishops, priests, and laypersons in other countries during the upcoming Synod.

During that synod, to be held in Rome in October, German lay leaders led by KDFB will provide more details as to the changes they are pursuing.

A summary of seven points of their ideas is on a letter to bishop Bertram Meier of Augsburg:

- “There is no theological justification for denying women access to all services and offices, including ordained offices”.

- Much more would already be possible without having to change Canon Law, as in the case of “administering baptism, assisting in marriage, and other ministries”.

- There is a need for “more courage and creativity in discerning how the gifts received and accepted can be appropriately placed at the service of the Church”.

- Also a need for a “synodal understanding of the office of priests and bishops”.

- And there is need for “broad change of the decision-making processes in the Church”.

- The Church also needs “transparency of decisions and accountability of all leaders”.

- It is necessary to preserve “the unity of the Church and its diversity too”.

The letter is available only in German at the KDFB website here (opens a pdf file), as part of their most recent press kit.

KDFB is regularly active at Instagram, and you can turn automatic translation of some features at that social media. One of their most recent postings appears after this paragraph and from there it is possible to find more information about them and their proposals on the clergy sexual abuse crisis and other topics.