PARIS (FRANCE)

New York Times [New York NY]

September 14, 2024

By Aurelien Breeden

Abbé Pierre campaigned for decades against homelessness and poverty. Revelations about his treatment of women have destroyed his image as a symbol of virtue in France.

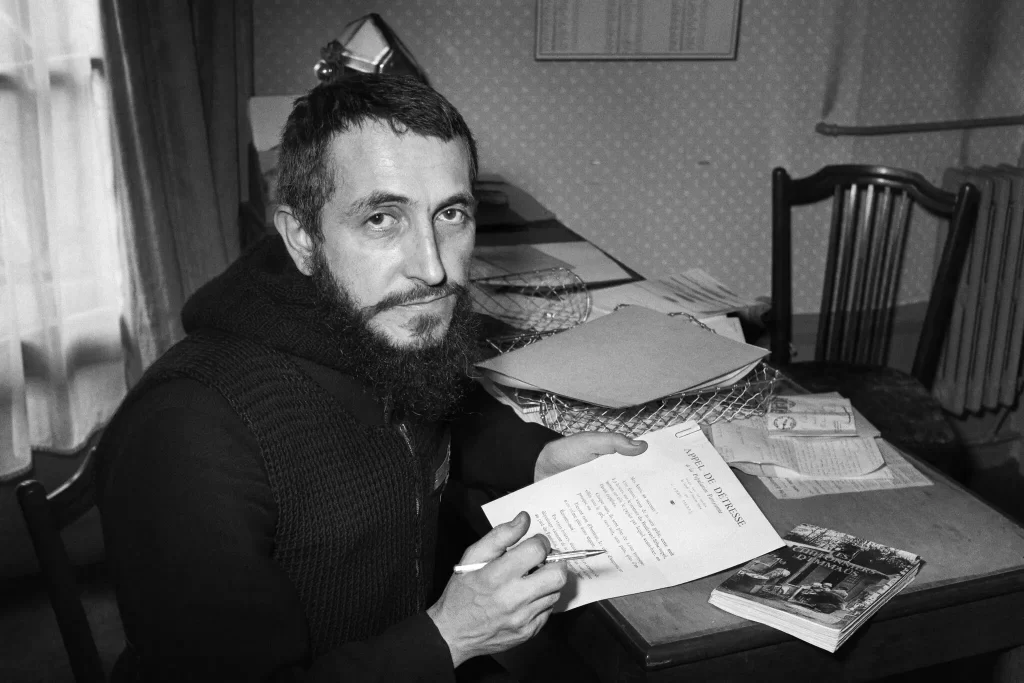

Abbé Pierre, a Roman Catholic priest who crusaded against homelessness in France, is such a celebrated figure in the country that television viewers once voted him the third-greatest French person of all time. Streets, schools and public parks are named for him. He was seen as a steady moral compass for the nation, even after he died at age 94 in 2007.

But over the past two months a much darker image has emerged: that of an accused sexual predator.

Years after his death, Abbé Pierre is facing a sudden profusion of sexual harassment and assault accusations — a stunning fall from grace that has prompted soul-searching at the social justice movement he started; raised uncomfortable questions about who knew about his behavior toward women; and unsettled a country that once hailed him as a symbol of virtue.

“The image of purity, of solidarity, of empathy that he had is crumbling,” said Axelle Brodiez-Dolino, a historian at France’s National Center for Scientific Research who has written a book about Abbé Pierre and Emmaüs, one of the nonprofit organizations that grew out of the movement he founded to address poverty and homelessness.

“That doesn’t change the good that he did in the past,” she added. “But there was a dark side to him that the broader public was completely unaware of.”

Two reports, commissioned by the nonprofits and published in July and this month, have laid bare accusations that Abbé Pierre sexually harassed or assaulted at least two dozen women between the 1950s and the 2000s, mostly in France but sometimes abroad, including in the United States. The accusations have been made by the women themselves, by members of their families, or by witnesses.

One woman said Abbé Pierre groped and kissed her when she was 8 and 9 years old in the mid-1970s. Another said he forced her to watch him masturbate and to perform oral sex on him in 1989. Yet another said Abbé Pierre abused her after she asked for help finding housing in the early 1990s.

The reports do not publicly identify anyone who came forward, but say the accusers were nonprofit employees or volunteers, members of families close to him, staff members at establishments he visited or people he met through his charitable endeavors.

The reports were compiled by Groupe Egaé, a private consulting firm that specializes in preventing sexual and sexist violence. It conducted an investigation at the request of the nonprofits — the Abbé Pierre Foundation, Emmaüs France and Emmaüs International — after a woman came forward privately in 2023, accusing the priest of sexual assault. The organizations say they believe the accusers and expect more to come forward.

“Our movement knows what it owes to Abbé Pierre,” the organizations said in a joint statement. “Now, we must also confront the unacceptable suffering that he forced upon others.”

Abbé Pierre, born Henri Antoine Grouès in 1912 into a wealthy silk-merchant family from Lyon, entered a Capuchin monastery at age 18. He fought with the French Resistance during World War II, served as a chaplain in the French Navy and became a lawmaker.

He campaigned for the homeless, issuing a famous radio call for shelter and supplies during the harsh winter of 1954. That effort inspired a 1956 law that is still in effect in France, making it illegal to evict tenants during the coldest winter months.

After that, not even the occasional brush with controversy dented his national image. He topped a newspaper ranking of France’s most popular personalities 17 times.

Now the nonprofits he left behind are scrambling to distance themselves from a man who was inextricably linked to their work. While he was rarely involved in the day-to-day running of their operations, his scruffy beard, black beret and cape made him an instantly recognizable advocate.

The Abbé Pierre Foundation said that it was going to change its name. Emmaüs France said it would move to remove his name from its logo. An independent commission of experts will investigate how he was able to act unimpeded for more than half a century.

“What we are trying to do through these measures isn’t to forget Abbé Pierre or obfuscate his role,” said Adrien Chaboche, the chief executive of Emmaüs International. “What we are changing is the way that we, as a movement and as associations, present ourselves to the world — and we can’t do that with a figurehead who now embodies such a disgraceful and reprehensible reality.”

They are not the only ones reassessing his legacy. Some cities in France have said they would be stripping his name from public spaces. Nancy, in the east, said it would remove a plaque honoring Abbé Pierre that was affixed only months ago.

How much of his behavior was known to those close to him is unclear. The reports, and investigations in the French news media, suggest that some people close to him knew he had a problematic attitude toward women.

Some victims had alerted nonprofit colleagues or managers of the abuse, the reports said. One charity worker cited said female colleagues were advised not to meet with Abbé Pierre alone. And Martin Hirsch, who was president of Emmaüs France from 2002 to 2007, wrote in a newspaper in July that it was an open secret within the organization that he had once been sent to a psychiatric clinic in Switzerland “because his attitude toward women was problematic.”

Abbé Pierre had publicly confessed later in his life to having sexual relations with women as a priest. But years before the #MeToo movement and broader scrutiny of sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church in France, the focus appeared to have been more on whether he had broken his vows — and less on whether those relations were consensual.

Pope Francis said on Friday that he did not know when the Vatican had learned about the abuse but added that “certainly after his death, it became known.”

“Abbé Pierre was a man who did a lot of good but was also a sinner,” the pope said on the plane returning from a trip to Southeast Asia and Oceania. “We must speak clearly about these things and not hide them.”

Agnès Desmazières, a historian who has written a book about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, drew a parallel with the case of Jean Vanier, the Canadian founder of a French charity who was accused after his death of engaging in several abusive sexual relationships.

Mr. Vanier and Abbé Pierre were both charismatic figures admired for their charity work, she said. Each has since been accused of using that reputation to abuse women.

“In a way,” Ms. Desmazières said, “Abbé Pierre’s charitable success protected him.”

Ségolène Le Stradic contributed reporting.

A correction was made on Sept. 14, 2024:

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to a book by the historian Agnès Desmazières about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. The book will be published in early October; it is not recently published.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Aurelien Breeden is a reporter for The Times in Paris, covering news from France. More about Aurelien Breeden