|

Abuse Databases and Religious Culture: A Catholic perspective on addressing abuse in the Church

By Terry Mckiernan

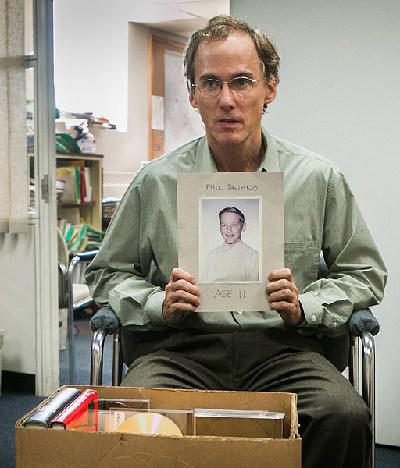

This is the third and last post in OSU’s current blog series on SNAP Mennonite’s MAP List (Mennonite Abuse Prevention List) and the broader issue of naming church workers (lay or ordained) who are credibly accused* of perpetrating sexualized violence. Today’s post is offered by Terry McKiernan, President of BishopAccountability.org, an organization focused on preserving a public record of sexual abuse and its cover up in the Catholic Church. He speaks from years of experience and offers the gift of wisdom that comes with a sustained commitment to doing what is needed to offer a voice to survivors and protect the vulnerable. The fact that this is the last post in our series does not mean that the conversation is over. The whole point of a series is to start conversation. If you have a story or perspective or question on the topic that you would like to share, don’t hesitate to be in touch. *** There is interdenominational precedent and momentum for religious communities to name publicly all church workers, living or dead, who are credibly accused of perpetrating sexual violence. I want to offer, in this piece, some background that sheds light on how Catholics and others have come to the same conclusion that SNAP Mennonite has landed upon, that a public list of the credibly accused must be maintained if church culture is going to change and start making progress toward rooting abuse out of their communities. THE EXAMPLE OF BERGEN CATHOLIC HIGH SCHOOL Venerable Kobutsu Malone is a Zen Buddhist priest. He’s worked as a chaplain at Sing Sing Prison in New York, and he’s served as a spiritual advisor for men on death row. He’s also a patent-holding mechanical engineer who’s developed adaptive electronic equipment for handicapped people. And Kobutsu is a survivor of clergy abuse. Back in 2002, when the Boston Globe broke the Catholic abuse story, Kobutsu was moved to come forward about the sexual abuse that he suffered as 14-year-old Kevin Malone at Bergen Catholic High School in Oradell, New Jersey. The searing document that he produced about that experience became the portal to a remarkable website, bergencatholicabuse.com. Other students at the school, which is run and staffed by the Irish Christian Brothers, contacted Kobutsu about their experiences, and he began to name and list the accused on his site, providing photographs of the brothers, documents, articles, and testimony from dozens of victims. Last week it was revealed that the Christian Brothers of Bergen Catholic had paid Kobutsu’s list the ultimate compliment. He had been the first survivor from the school to come forward, and his website had been the catalyst for many other survivors. Now Bergen Catholic offered to include Kobutsu in a $1.9 million group settlement with 21 survivors, but asked that he take his website down. Kobutsu refused. THE POWER OF NAMES AND LISTS In this blog post, I’d like us to reflect together on the power of names and lists – why have they been so important for survivors of sexual violence in religious institutions? I’ll talk about the Mennonite Abuse Prevention (MAP) List, which is the subject of this series at Our Stories Untold, and the Database of Accused that my organization, BishopAccountability.org, has maintained for ten years. But my real subject is the community of understanding that forms around survivors’ activism – Kobutsu Malone, Barbra Graber, and many others. SURVIVORS FIRST We’ll be discussing the naming of ministers, priests, and other church workers who commit crimes of sexual violence, but let’s remember that if we are to learn about those crimes, we depend entirely on the innocent victims of those attacks for our knowledge. The perpetrator and his protective institution work to keep the abuse a secret. We only learn the truth if the survivor comes forward. Yet the survivors’ names, their identities and achievement, are often neglected. For example, Carolyn Holderread Heggen and Martha Smith Good, together with six other courageous women, provided accounts of their abuse to a Mennonite investigation in February 1992, and signed a statement summarizing their experiences. The famous perpetrator, Mennonite peace theologian John Howard Yoder, had taken particular care to abuse them secretly. Marlin Miller, who was Yoder’s protégé and successor as president of Goshen Biblical Seminary, had even discussed with Yoder and implemented a plan to “liquidate” Miller’s “secret file” of contacts with Yoder’s victims, so as to prevent “scandal.” But even in disgrace, Yoder often drifts to the center of the frame. Books and conferences of Yoderians ignore as best they can his serial abuse of more than 100 women. The liquidation of those survivors’ letters, each of them so difficult to write, was not complete. Miller wrote a summary of all the survivor correspondence, which he stored at his home, not at the office. Rachel Waltner Goossen’s citation reads: Marlin Miller, “notes from correspondence which has been destroyed,” handwritten, 22 pages, c. 1980. If Heggen and Good and many other women had not decided to name themselves as Yoder’s victims, and to endure the backlash and fraught relationships with their Mennonite identity that resulted, the truth about Yoder might never have come to light. So as we discuss the naming of perpetrators and enablers, we must remember that those names become public because the survivors courageously choose to name themselves first. Surely, it is their right to identify the person who violated them, and it is in the public interest that they do so, if they wish. Survivors also have the right to decide how public they wish to be about their own identities. Writing for Our Stories Untold, survivor Sharon Detweiler provides a devastating prosecutor’s analysis: “Yoder’s position and reputation – and the Mennonite Church’s position and reputation – had always been the paramount concern.” But she chooses the level of detail to offer about her own experience, welcoming the reader while maintaining her privacy. A BRIEF SURVEY OF COMMUNITIES AND CATHOLIC ABUSE DATA Barbra Graber writes in “Why We Name Names” about the benefits of the future MAP List that “burned a hole in my heart each time I added another name” – healing, prevention, deterrence, reassurance, and renewed trust. Similarly, the movie Spotlight dramatizes survivor Phil Saviano’s meeting with the Boston Globe reporters, whom he tells of the list of 13 priest offenders he’d gathered at the local SNAP meetings that he led. This is how it has worked – communities of survivors gather, and inevitably they gather the names of their perpetrators. Within any list of survivors is the list of the offenders and enablers, ready to be brought into the open among friends. In the Catholic experience, the first major effort to build a list of clerical perpetrators was launched in the 1990s by The Linkup, an organization of survivors and supporters that included Jeanne Miller (the founder), Tom Economus, Jay Nelson, Gary Hayes, and Marilyn Steffel, among many. Their list of 666 “Fallen Catholic Clergy” was based on an indispensable snail-mail newsletter, Missing Link, that offered a digest of press coverage called “Black-Collar Crimes.” As the second wave of the Catholic abuse crisis crested in the 1990s, some reporters began to consider it from a national and even a global perspective. Their files began to look very much like the lists and databases we’ve been discussing here, with folders of news articles, legal complaints, and church documents alphabetized by the names of accused and enabling clerics. The index of Jason Berry’s genre-defining Lead Us Not into Temptation, published in 1992, was a kind of proto-database. As Berry showed in his book, the Vatican and the U.S. bishops’ conference had preceded him in the data-gathering work. He told the story of whistleblower Fr. Tom Doyle, who collected information for the Pope’s representative in the U.S., Archbishop Pio Laghi, as the first wave of the crisis broke in the early 1980s in Louisiana. Doyle’s attempt to advise the U.S. bishops on the crisis, a 1985 report he co-authored known as the Manual, shows the encyclopedic picture he’d begun to assemble with his co-author, Fr. Michael Peterson, who ran the bishops’ treatment facility in D.C. By the mid-1990s, attorneys had handled enough Catholic clergy cases that they too were assembling their lists and databases, led by Jeffrey Anderson and Stephen Rubino. Attorney Sylvia Demarest was on the team that won a $119.6 million jury award for 11 Dallas victims of Fr. Rudy Kos in 1997. She had also been quietly building a visionary national database of the Catholic abuse problem, and when she donated her database and documentation to BishopAccountability.org, it formed the core of our Database of Accused, along with a volunteer effort by Boston-based Survivors First. During the third wave of the Catholic crisis that broke in 2002 with the Globe’s reporting, more and more survivors came forward, and media reports of their abuse were collected on the internet by the Poynter Institute’s Abuse Tracker, now hosted by BishopAccountability.org. The Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), led by Barbara Blaine, David Clohessy, Barbara Dorris, Peter Isely and many others, had been very significant in the 1990s, along with the Linkup and Survivor Connections, founded by Frank Fitzpatrick. But in the 2000s SNAP emerged as the organization that helped survivors cope and come forward. Founded in 1988 SNAP now has more than 21,000 members in 79 countries. The resulting media coverage and investigative reports were captured by BishopAccountability.org, allowing us to grow our database and deepen it. Our database now identifies and provides information, sometimes in great detail, on 4,220 accused bishops, priests, nuns, brothers, and seminarians. But data released by the U.S. bishops show that they know of more than 6,528 clerics who are credibly accused of molesting more than 17,651 children. So the work of our database continues. THE WORK OF THE DATABASE At BishopAccountability.org, the database work is guided by a posting policy that defines our acceptable public sources and provides for correction, including the exclusion of allegations that are recanted or proven extortionate. The policy is an inclusive one, and we make it clear that we are aggregating allegations, not deciding whether they are credible. As we maintain and enhance our U.S. database and begin to build databases for other countries (see, e.g., Argentina), we are more and more aware of the complexity of the abuse crisis. It can be usefully analyzed from many perspectives. When I wrote the lists of cities for the end of Spotlight (see the text and video of the lists), I was encouraged to see the abuse crisis across that dimension – there is a geography of abuse. The timelines of a priest’s career and abuse history, and of his manager’s tenures, overlay that geography in very complex ways. Yet those complexities are just the beginning of the work. We are studying acts committed in secret and maintained as corporate secrets within an insular culture. Many offenses and offenders will never be known, as a new report by Madeleine Baran of American Public Media, one of the great reporters on this subject, will soon show. ARCHIVING THE SILENCE In her “Archiving a culture of silence” for this series, Stephanie Krehbiel writes about the incompleteness of this work. In the MAP List project, she says, “the difference in length between the short public list and the long private list is one of the reasons I keep going to therapy.” The research required to bring a name onto the public list is great, and the litigation that produces documents is scant, and the enablers are many. At BishopAccountability.org, we too know survivors who are not ready to come forward, and most dioceses have not experienced the transparency that investigative reporting and criminal inquiries bring. As with the Mennonites, Catholic leadership has improved its policies and systems, while leaving much of the culture the same. Thousands of clerical sex offenders have not yet been identified. But Krehbiel quotes constitutional scholar Marci Hamilton: “This is the era in which institutions are learning that they simply cannot keep their secrets about sexual abuse and assault to themselves, no matter how hard they try.” THE BISHOPS’ LISTS One example of that change, in the U.S. Catholic experience, is the growing number of dioceses and religious orders that have posted on the internet their own lists of accused. As of this writing, 33 Catholic dioceses in the United States, and 6 provinces of Catholic religious orders, have published lists of credibly accused, totaling more than a thousand names. Some of them explained their actions in terms quite similar to the rationale Barbra Graber laid out in Our Stories Untold, when she discussed the MAP List. (See, e.g., the bishops’ explanations of the lists for Wilmington, Boston, and Seattle.) A small but growing number of U.S. bishops seems to see lists of accused priests as worthwhile. This isn’t a story of wholesale Catholic enlightenment. No lists have been posted by 145 other U.S. dioceses and scores of religious orders. Most (but not all) the lists simply acknowledge names already made public by survivors, their attorneys, and law enforcement. For example, Cardinal O’Malley included no new names when he released his Boston list in 2011, leaving it to the Boston Globe, once again, to provide the public with a list of accused priests unacknowledged by the archdiocese. So the Catholic experience is very mixed, and transparency is partial at best. But every list repays careful study. The various Catholic lists can still be useful to Mennonites and people of other denominations:

UNDERSTANDING THE DEEP CULTURE AND ACTING ACCORDINGLY So there is interdenominational precedent and momentum for the solution Barbra Graber is urging: “We ask all Mennonite church agencies and institutions to publicly post the names of all credibly accused church workers, living or dead, who have been dismissed from a post for any type of sexual misconduct.” The specific benefits that Graber sees are real, and I also believe that a more general benefit can come from greater transparency. We are progressing from lists of names, to detailed information on assignments and offenses, to collections of documents on an accused person that allow us to understand how the institution enabled his crimes – and even more broadly, how a religious culture can foster behavior abhorrent to all people of faith. In the Catholic context, those collections of documents have been crucial for deepening our understanding. Recent litigation has forced the release of large document archives, and some dioceses, making a virtue of necessity, have posted those archives on their websites. So here are the documents from the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, where a brutal bankruptcy fight has just ended, as served on the website of the survivors’ attorney Jeffrey Anderson, the Journal Sentinel newspaper, and the archdiocese. For other examples, see the archdiocesan files of Portland OR, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Again, caveats are in order. These documents were not released voluntarily, and there were bruising battles over withholding certain documents and redacting others. But we are very unevenly, and despite horrendous setbacks and ongoing abuse, deepening our ability to understand the character of sexual abuse in a religious context, and the managerial and cultural reasons why abuse was allowed or even enabled. For Catholics, I believe this entails acknowledging the Catholicity of the abuse done by Catholic clergy. Of course, the abuse is similar in some ways to child abuse perpetrated by family members, or public school teachers, or Boy Scout leaders. But it is also very Catholic, in ways that I believe mean a great deal. For example, much of the abuse of children by Catholic priests had to do with the sacrament of confession. Priests scouted in the confessional for victims. They researched vulnerable families in the confessional. Sometimes they abused their victims there. And over all this despicable behavior loomed the confessional’s crucial role in Catholic subjectivity – how we became Catholic persons. It’s no surprise that, at least in theory, Rome takes a very hard line on what it calls solicitation in confession. To take another example, the abuse of boys and girls in Catholic high schools was similar in some ways to abuse perpetrated by public high school teachers. But it was also very different. The charism of the religious order that ran the high school influenced everything that occurred there – especially the abuse. If the high school was a so-called minor seminary – a seminary high school – the culture of the school was extreme, and often the abuse was too. As I read Goossen and Krall and Detweiler on John Howard Yoder, I was often reminded of the Catholicity of abuse. It seemed to me clear that Yoder’s abuse of his female victims was very much a 20th-century Anabaptist abuse. His victims had the great misfortune of crossing paths with the man who reinvented pacifism and even Jesus himself for Mennonites trying to live their 16th-century Reformation in the modern world. As a devotional Catholic, not really left or right, I can relate. Yoder appears to have set the theological terms of Mennonite life, and the theological terms of his abuse of women, and even the terms of the investigation that his friends and vassals in Mennonite academia tried half-heartedly to press against him. What should have ended at the police station and in the criminal courts spun slowly out of control in years of debate on how to apply Matthew 18 to Yoder’s abuse of more than 100 women. The Yoder who wrote The Politics of Jesus was the dominant presence in 20th-century Mennonite life. Surely it’s impossible to understand his abuse of women without including his theology in the reckoning, and his theology seems gravely implicated in the abuse he structured as a kind of perverted citation and implementation of his theories. This is a bitter pill. So is the widespread sexual abuse of children by clergy in a Catholic church whose art and understanding of salvation is centered on the Christ Child. Instead of minimizing the Catholicity of abuse (as the bespoke reports of the John Jay College 2004, 2006, and 2011 did) or trying to parse Yoder’s theology apart from his theologized abuse (as the Yoderians do), the abuse crises in the Catholic and Mennonite churches must be accepted as inherent – the crises must be owned, if they are to be vanquished. For this task, the lists and databases and document archives are tools for understanding, and from understanding and willingness to act will come a true solution to these terrible problems. On the willingness to act, the “binding and loosing” quandary of the Yoder case teaches us an important lesson, as does the Catholic church’s practice in these cases. Civil litigation, criminal prosecution, official inquiries, and reform of the statutes of limitations and the reporting laws – these are the keys to effective action and reform, for churches and society both.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.